Overview

Expressionism By Andrew, Nell; Jordan, Sharon; Głuchowska, Lidia; Poppelreuter, Tanja; Conrath, Ryan; Jordan, Sharon; Głuchowska, Lidia; Poppelreuter, Tanja; Conrath, Ryan; Andrew, Nell

Overview

Abstract

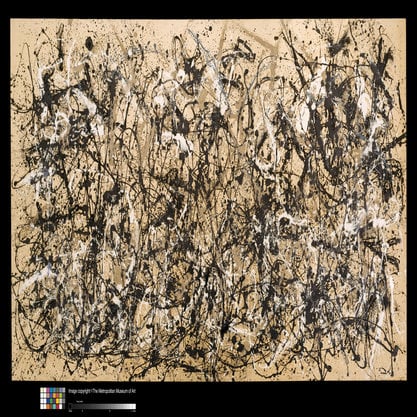

Expressionism was one of the foremost modernist movements to emerge in Europe in the early years of the twentieth-century. It had a profound effect on the visual arts, as well as on music, dance, drama, literature, poetry, and cinema. Rather than depict physical reality, Expressionism developed as a reaction against the prevailing interest in positivism, naturalism, and Impressionism, as artists who were heavily influenced by the work of Edvard Munch and Vincent Van Gogh sought to explore subjective content, finding the visual means to fully evoke or express an emotion, mood, or idea through their artwork.

Expressionism’s theoretical underpinnings reside in Friedrich Nietzsche’s (1844-1900) philosophy and in Wilhelm Worringer’s (1881-1965) Abstraktion und Einfühlung (Abstraction and Empathy, 1908). In expressionist works, emotions and tensions were depicted with the help of symbolic color and lines in the belief that both carry their own innate expressive meaning and have psychological and spiritual effects—a strand of thinking pursued by Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) in his 1911 book Concerning the Spiritual in Art (Gordon, 1987).

German Expressionism

Expressionism was one of the foremost modernist movements to emerge in Europe in the early years of the twentieth-century. It had a profound effect on the visual arts, as well as on music, dance, drama, literature, poetry, and cinema. Rather than depict physical reality, Expressionism developed as a reaction against the prevailing interest in positivism, naturalism, and Impressionism, as artists who were heavily influenced by the work of Edvard Munch and Vincent Van Gogh sought to explore subjective content, finding the visual means to fully evoke or express an emotion, mood, or idea through their artwork.

Expressionism’s theoretical underpinnings reside in Friedrich Nietzsche’s (1844-1900) philosophy and in Wilhelm Worringer’s (1881-1965) Abstraktion und Einfühlung (Abstraction and Empathy, 1908). In expressionist works, emotions and tensions were depicted with the help of symbolic color and lines in the belief that both carry their own innate expressive meaning and have psychological and spiritual effects—a strand of thinking pursued by Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) in his 1911 book Concerning the Spiritual in Art (Gordon, 1987).

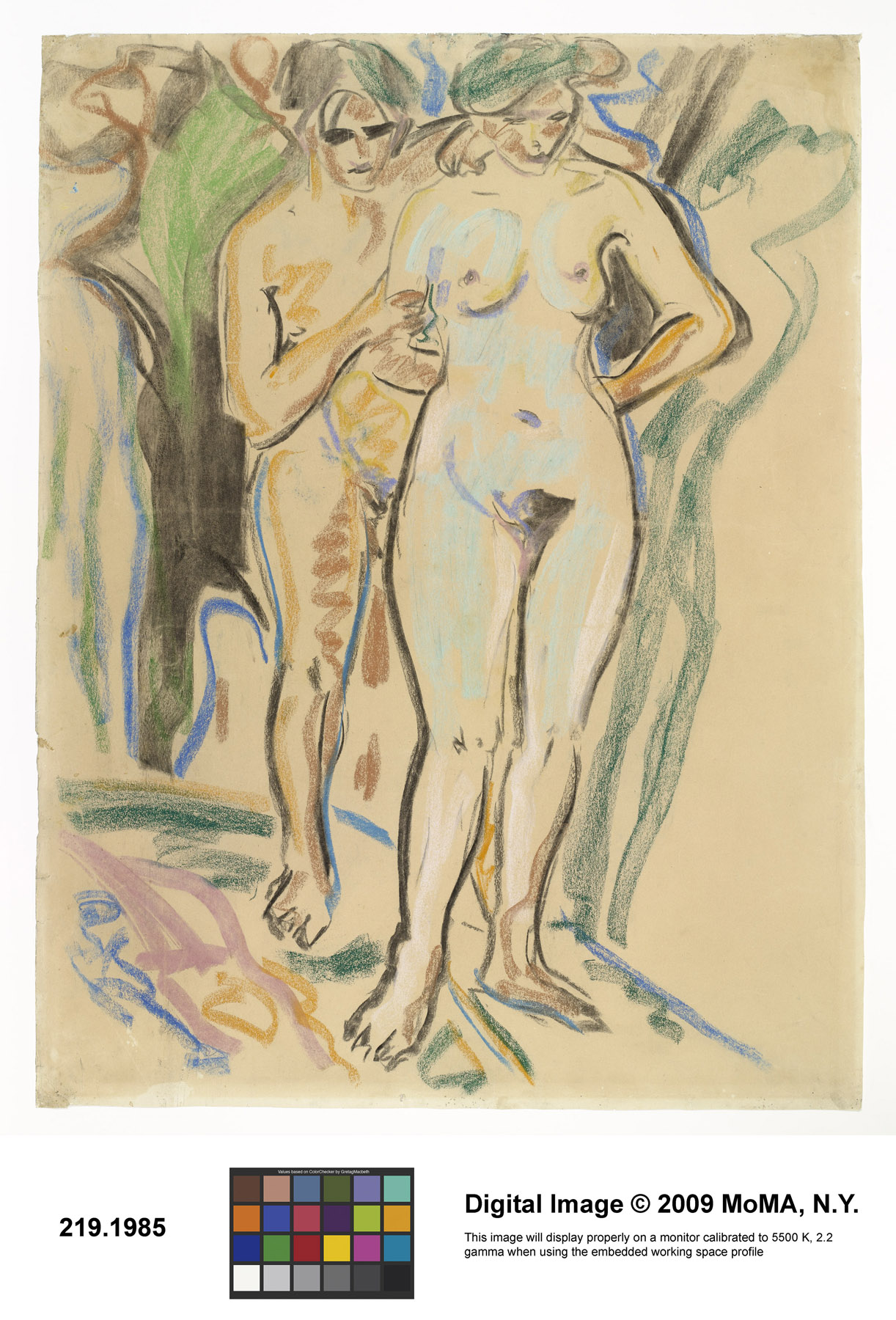

The term German Expressionism refers to an aspect of international modernism that dominated the visual arts and architecture in that country toward the end of the Wilhelmine Empire through the early years of the Weimar Republic (from approximately 1906 to 1922). Artists associated with the term used a multiplicity of antinaturalist techniques to attack not only the conventions of nineteenth-century academic art but also the conventions of a society they found repressive, materialistic, and corrupt. Experimenting with emotive color, form, and composition, artists such as Wassily Kandinsky (fig. 1) and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (fig. 2) were determined to communicate utopian visions synthesized from an array of international, anti-establishment cultural and political ideologies such as theosophy, anarchism, and socialism.

Source: Image used courtesy of The Art Institute of Chicago.

Source: The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence .

As early as 1911, critics in Germany had begun to use the term "expressionist" to refer to contemporary works of European art that turned away from naturalism and Impressionism. By 1912, the director of the Cologne Sonderbund exhibition described its survey of the most recent developments of painting as Expressionismus and emphasized the international number of artists from France, Austro-Hungary, Russia, and Norway, in addition to Germany, who were simplifying and intensifying their colors and forms. Among the artists included in this exhibition were Henri Matisse of the Parisian Fauves, Kirchner and Erich Heckel of the Dresden/Berlin Brücke (Bridge), Kandinsky of the Munich Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider), and Cesár Klein of the Berlin Neue Secession.

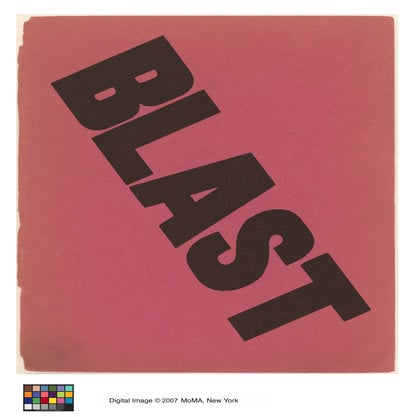

Provincial artists such as Carl Vinnen and the general public reacted negatively to the bright colors, flattened shapes, and distorted forms of Expressionism, continuing a long-standing aspect of German thought in which internationalist influences were seen as the direct cause of the decline of German art and culture. Supportive critics, however, cited earlier precedents such as oils by Grünewald and Michelangelo in addition to works by contemporary northern artists such as Edvard Munch to justify the anti-naturalism of the new direction. Worringer stressed the metaphysical values of the new artistic tendencies and urged the study of "primitive art" to overcome the focus on the world of natural appearance perpetuated by the classical-Renaissance tradition of European art. Artists, aware that much of the public was bewildered by their work, felt compelled to explain their approach in essays, tracts, and manifestos. Periodicals such as Der Sturm (fig. 3) and Die Aktion reproduced numerous prints from Brücke, Blaue Reiter, and Neue Secession artists, as well as recognizing sculptors, architects, and poets as Expressionists. Even during World War I, Der Sturm and its gallery continued to explain the new tendencies as international by promoting Futurism and Cubism as part of Expressionism.

Because of the dominance of the state in artistic affairs during the Wilhelmine Empire, visual artists as well as architects such as Bruno Taut struggled to free themselves from national or state regulations that might determine the direction and content of their works. Social anarchism, with its promise of mutual help and a state that would wither away, set the frame for many Expressionists’ utopian and optimistic estimates of the possibilities of individual creativity. At the same time, most endeavored to explore communal activities and to weigh their responsibility to the public.

The World War I became a catalyst for an even more activist stance among many Expressionists. With the collapse of Imperial rule in 1918 and the formation of the Weimar Republic, many artists who had been connected to expressionist groups before the War established new organizations such as the Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Work Council for Art) (fig. 4) and the Novembergruppe (November group) which initially supported free art education, public museums, and local participation in housing and other public projects. Now infused with French Cubism and Italian Futurism, Expressionism became a visual signifier for the new Republic with its opposition to the Imperial past and evocation of internationalist innovation. But the anti-naturalism that most Expressionists believed would stimulate change met with resistance from the workers they wished to inspire. As the strikes and street battles of 1919 weakened the German Republic, many artists and critics became disillusioned with the governing Social Democrats and turned dramatically against the Cubo-expressionist style manifest in election posters (fig. 5) and other visual images of the Republic commissioned by the majority party. Communists such as George Grosz and John Heartfield distanced themselves from their expressionist pasts and many of the original supporters of Expressionism, such as Worringer, wrote of its demise. While Expressionism was approaching its end as far as the artists themselves were concerned, during the 1920s, the urban middle class embraced the stylistic manifestations of Expressionism particularly in theater design and film, and references to Expressionism survived in the visual manifestations of Dada and Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity).

During the 1930s, Expressionism was attacked by both the extreme right and left. The Marxist critic Georg Lukács severely criticized Expressionism, and modernism more generally, for its fragmented, abstracted forms and inability to communicate to the masses. His 1934 essay "Grösse und Verfall des Expressionismus" ("The Rise and Fall of Expressionism") set the tone for later criticisms during the 1980s. The National Socialist condemnation of Expressionism and modernism reached its apogee with the 1937-1938 traveling exhibition of Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art).

With the conclusion of World War II, Expressionism was resurrected in Germany and the United States as an antipode to the authoritarian realisms of both Soviet and National Socialist regimes. In the 1950s, art historians and critics began to publish studies of pre-World War I German Expressionism, but scholars did not begin to explore the second generation of Expressionists until the 1970s and 1980s. However, many texts republished following World War II have since become accepted as canonical. Nonetheless, not until the end of the last century and the beginning of the twenty-first, have scholars asked why museums in the United States and England have favoured Cubism over its modernist cousin, Expressionism, in exploring the trajectory of modern art.

Austrian Expressionism

Austrian Expressionism is primarily associated with the work of Egon Schiele and Oskar Kokoschka, but also includes the work of their contemporaries Max Oppenheimer, Richard Gerstl and Alfred Kubin. For Schiele and Kokoschka, portraiture and figural imagery, often favoring scenes of heightened sexual tension, were primary subjects as each sought to delve beneath the surface reality of physical appearance to uncover psychological or emotional insights. Both artists reflect the importance of the psychological theories of Sigmund Freud, particularly his On the Interpretation of Dreams (1900). Like their German counterparts in Die Brücke group, Schiele and Kokoschka took inspiration from the authentic and natural behavior of children.

Schiele and Kokoschka got their start in Vienna, thanks largely to the support of Gustav Klimt, though their early works generated consternation and criticism when exhibited. By showing the untidy reality and complexity of the individual human psyche and the overriding forces of instinct, sexual desires, and physical or psychological illnesses that control and define a person, their works posed a direct challenge to the reserved nature of the Viennese, for whom outward appearances were central to maintaining societal expectations.

Kokoschka encouraged his subjects to move about freely and behave naturally as he worked, without the use of preliminary sketches, to uncover the essence of a sitter. Portrait of Hans and Erika Tietze (1909) depicts a married couple, both of whom were respected art historians (fig. 6). Influenced by the development of x-ray technology, Kokoschka incised directly onto the surface of the canvas to include force lines emanating from each figure, while adding linear motifs to surround them with a harmonic assortment of abstract colors and forms. Though individualized and separated through pose, they are united through the position of their hands, which create an arching line across the foreground of the canvas to pull them together.

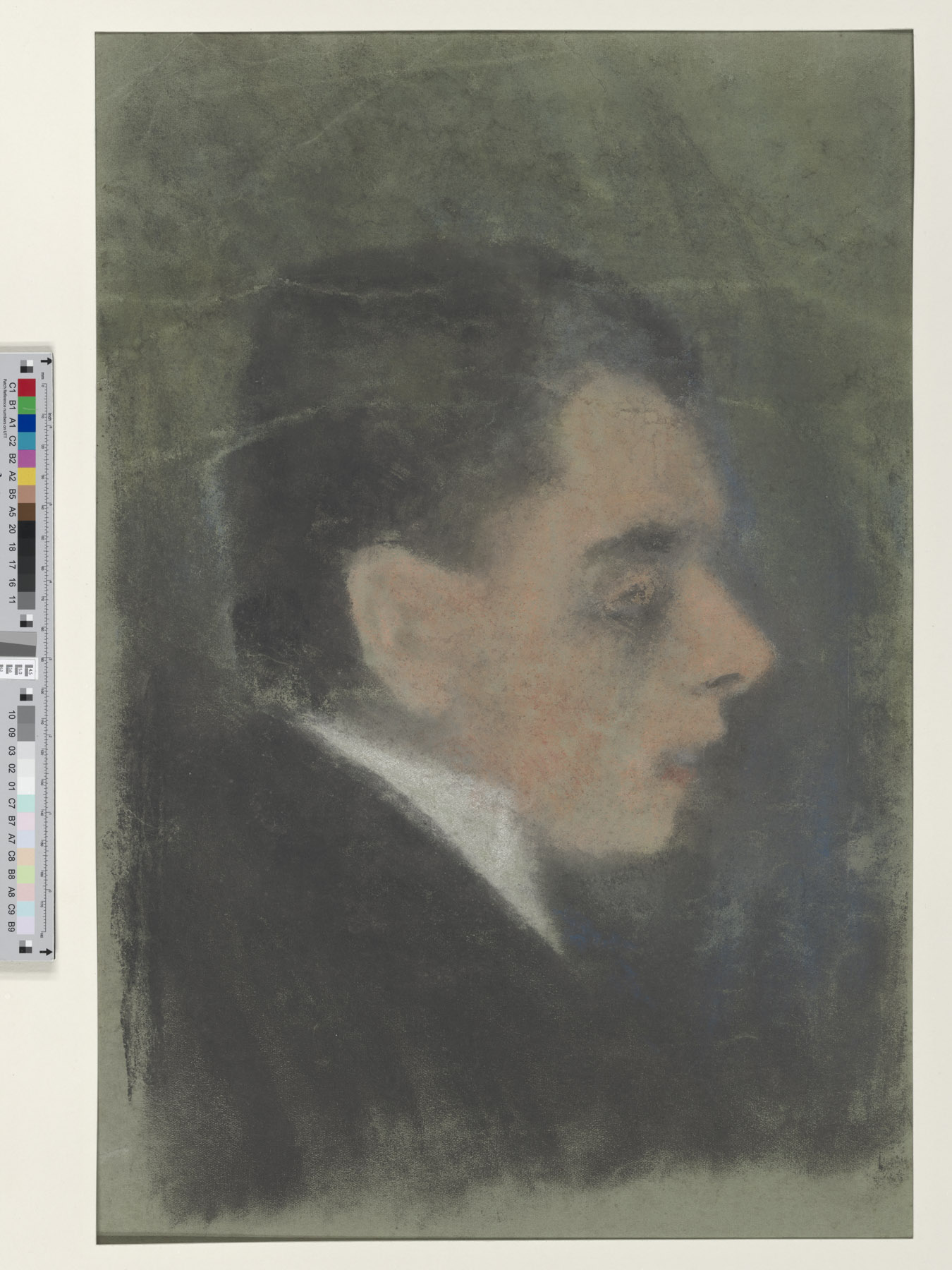

In Portrait of Paris von Gütersloh (1918), Schiele’s friend and fellow artist is rendered in his distinctive, energetic line and the architectural structure of form found in his paintings (fig. 7). The sitter’s dominance within the vibrant orange background, punctuated with jolts of color in the blue tie and red socks, gives a sense of dynamism and intensity to the figure that corresponds to his creative identity. In Portrait of Johann Harms (1916), Schiele elongates the form of his elderly father-in-law and includes a resigned gesture that conveys the awareness of deteriorating health and loss of physical vigor, which is further manifest in the somber, melancholy palette (fig. 8).

© DACS 2016

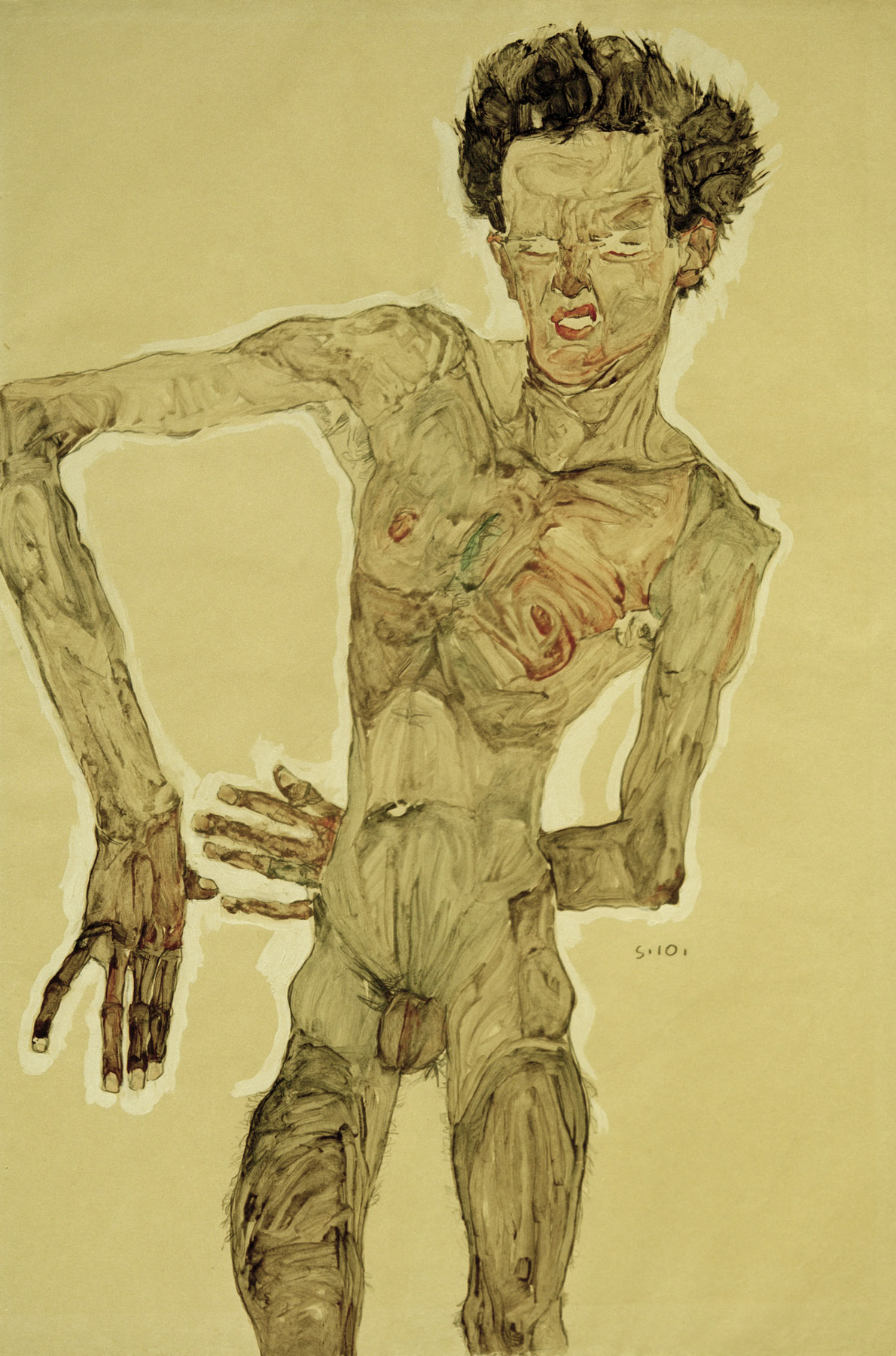

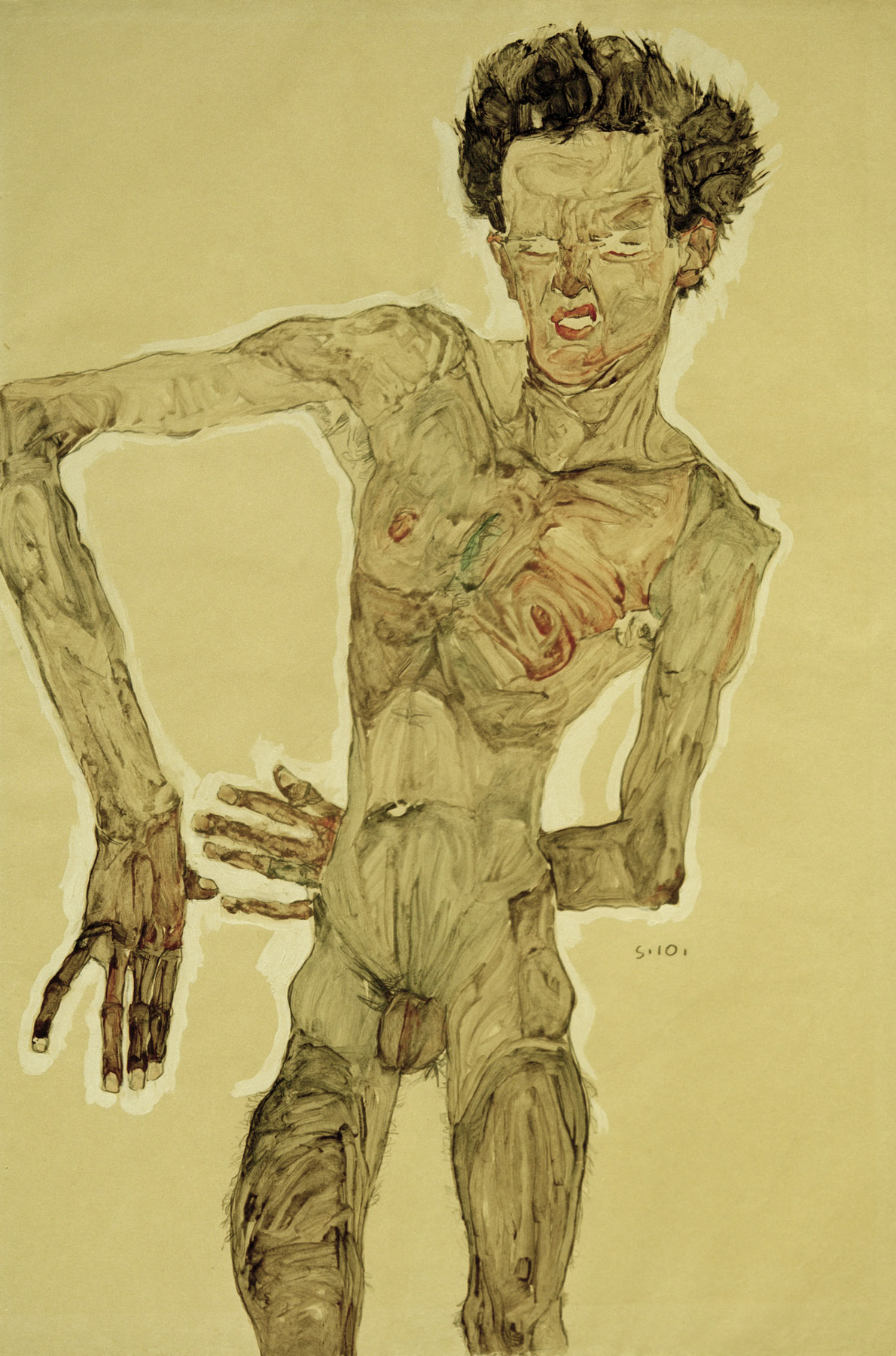

Schiele and Kokoschka were aligned in the usefulness of self-portraiture to study the power of pose, gesture, and facial expression, and throughout their works, the position of the hands is often central. This is seen in several examples, including Schiele’s Self-Portrait (1910), in which he assumes a defiant and anti-authoritarian stance to signal his renegade arrival on an artistic scene that so prized the opposite type of portraiture, one that conveyed status and social position through objective details (fig. 9).

akg-images

Kokoschka’s early Self-Portrait, 1909, a clay bust, shows the expressionist interest in surface texture and the intense handling of form (fig. 10), which are also key elements in expressionist canvases. In one of his most famous works, Kokoschka is able to offer insight into his psychological state of mind during a defining love affair with Alma Mahler. In The Tempest (Bride of the Wind) (1914), the couple appears within an ethereal realm of color within an atmospheric landscape (fig. 11). But, the deterioration of their relationship is signaled by the cool blue tones and through the worried expression on the artist’s face, matched with the tension of his writhing hands.

Source: akg-images.

Kokoschka was the author of several dramatic plays that relied on non-linear narrative structure and aphoristic content, while Schiele wrote poetry using alliteration and rhythmic construction to heighten the sensual descriptiveness of his prose. This literary work is part of the larger reorganisation and regeneration in languages of creative form within Expressionism. In Vienna, one of the most profound and influential mediums was music. Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern and Alban Berg experimented with atonal compositions, harmonic dissonance and strong subjective allusions, showing the capability of Expressionism to express deep meaning by transcending existing limitations.

Polish Expressionism

In contrast to the German movement, Polish Expressionism did not involve a whole generation of artists but only a small part of it. Historical Expressionism (1910-1925) played only a marginal role in Polish artistic life; more important was the early, symbolist Expressionism at the turn of the twentieth century, with its affinity for hyperbole and grotesque expressions in the prose and poetry of Jan Kasprowicz, Tadeusz Miciński, Wacław Berent, and Roman Jaworski. In the visual arts, it was characterized by an anti-naturalist deformation of space and the use of color accompanied by existential themes in the works of Władysław Podkowiński and Stanisław Wyspiański. Unique in this context are the abstract, "musical" compositions of the Warsaw painter Mikalojus Čiurlionis.

The work of Edvard Munch and Gustav Vigeland, popularized by Stanisław Przybyszewski, provided an important influence for artists such as Wojciech Weiss, Xawery Dunikowski, and Franciszek Flaum. Przybyszewski played a stimulating role in the biweekly Zdrój (Source, 1917-1922, edited by Jerzy Hulewicz in Poznań), a leading forum of the only programmatic expressionist circle in Poland. This artist group included Margarete and Stanisław Kubicki, Władysław Skotarek, Stefan Szmaj, and other less radical artists who programmatically used the bilingual name Bunt (Polish – Revolt, German – colorful, 1917-1922) and employed linocut as an egalitarian artistic medium. The Kubickis and Hulewicz also produced the earliest examples of abstract art in Poland. The first group exhibition in April 1918 was a succès de scandale because of its social and political provocation, promoting sexual liberation and international spirit in a traditional and national oriented milieu. The second exhibition was organized at the Berlin gallery Die Aktion in June. The following three shows in Poznań and Lvov in 1919 and 1920 were organized in collaboration with the Formiści group (Formists, 1917-1922) from Cracow and Young Yiddish (1919-1922) from Łódź. While Young Yiddish, like Bunt, was engaged in international leftist artistic activities, Formiści concentrated on formal questions, which initiated Art Déco, a Polish national style inspired by folk art, and distanced itself from any German connotations. Some artists of Bunt and Young Yiddish, who eventually became members of International Constructivism, cooperated with Der Sturm and participated in the Congress of the International Union of Progressive Artists in Düsseldorf and the International Exhibition of Revolutionary Artists organized by the Kubickis in Berlin in 1922. However, the writers of Zdrój with Jan Stur, like Formiści, tended to favour a Polonisation of Expressionism by looking for its genealogy in the Polish romantic tradition. The anthology of the movement was Zmierzch Epoki (Twilight of the Epoch, 1920).

Expressionism was also present as literary poetics in manifestations of Polish Futurism and Dadaism in Cracow and Warsaw. In the visual arts, it included the work of some Polish representatives of the École de Paris, among them Eli Nadelmann and Alfred Aberdam. The art works of Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz and the poetry of Józef Wittlin and the group Czartak (1922-28, founded by Emil Zegadłowicz) contained an original Polish contribution to late Expressionism.

Expressionism in Literature

Like their visual artist contemporaries, expressionist writers born in the 1880s and 1890s opposed the values of pre-war German Wilhelminian society, and reacted to the developments of modern urban civilisation. Expressionist writers tried to trigger their readers’ imaginations and to evoke their emotions. Though they are all connected via these central lines of theme and effect, the broad variety of literary style and form practiced by expressionist writers makes it notoriously difficult to arrive at a widely accepted definition of Expressionism, a problem mostly put aside today by regarding expressionist literature as a forerunner of postmodern heterogeneity.

In poetry, the effects of urbanisation and mechanisation were expressed by lining up disparate images in paratactical style ("Reihungsstil"), showing the new perceptional demands caused by acceleration, new technologies and media (see the poems of Jakob van Hoddis, Alfred Lichtenstein and Ernst Blass), leading to the "dissociation of self" ("Ich-Dissoziation", Vietta) and to the impersonality of a technicized society (Gottfried Benn, "Morgue"-poetry). Symbolic imagery and synaesthesia are characteristics of the poetry of Else Lasker-Schüler, Georg Heym, Georg Trakl, and Ernst Stadler, all of whom wrote poems in regular form and rhyme as well as free verse. By contrast, August Stramm’s poems disposed of conventional language structures.

Authors of expressionist prose likewise discharged conventional patterns of narration and tried new techniques such as stream of consciousness and reflective prose ("Reflexionsprosa"), descending into the minds of their protagonists (Gottfried Benn, Gehirne, 1916; Carl Einstein, Bebuquin oder die Dilettanten des Wunders/Bebuquin or the Dilettantes of Miracle, 1912), often criminals or insane (Georg Heym, Der Dieb/The Thief and Der Irre/The Madman, 1912; Alfred Döblin, Die Ermordung einer Butterblume/Murder of a Buttercup, 1909). The Prague author Franz Kafka is often deemed an Expressionist because of the nightmarish visions of individuals lost in bureaucracy and mechanisation he presents, as in the stories "Die Verwandlung" ("The Transformation" or "The Metamorphosis", 1915) and "In der Strafkolonie" ("In the Penal Settlement", 1919) and in the novels Der Prozess (The Trial, 1925) and Das Schloss (The Castle, 1926).

Reinhard Johannes Sorge was the first to deal with the generational conflict in drama, showing the clash of values in Wilhelminian society in a family context in Der Bettler (The Beggar, written 1911, first staged 1917), a subject taken up for example by Walter Hasenclever (Der Sohn/The Son, 1914). Carl Sternheim’s plays (Der Snob/The Snob, 1912) are acid satires on outmoded bourgeois values, whereas other dramatists denounce the inhumanity of mechanisation and individual powerlessness, for example Georg Kaiser (Gas-Trilogie/Gas Trilogy, 1917-1920) and Ernst Toller (Masse Mensch/Man and the Masses, 1919; Die Maschinenstürmer/The Machine Wreckers, 1922), the latter with a highly political stance. Formally, many expressionist plays consist of a series of episodes, or stations, held together only by a central figure (‘Stationendrama’). Characterized by declamation and distorted language, expressionist drama tends to reduce characters to mere types or abstractions (August Stramm, Kräfte/Forces, 1915). Expressionist theater is often experimental, for example in depicting violence (Oskar Kokoschka, Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen/Murder, the Women’s Hope, 1909) or in trying to generate a synthesis of the arts ("Gesamtkunstwerk"; Wassily Kandinsky, Der gelbe Klang/The Yellow Clang, 1909).

Main influences on expressionist literature were Sigmund Freud’s psychological insights and especially Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophy. Of particular resonance was Nietzsche's nihilistic diagnosis of human life and transcendental emptiness, often succinctly conveyed in the mantra "God is dead," as well as his hymnic vitalism (Also sprach Zarathustra/Thus Spake Zarathustra, 1883/85), taken up by Expressionism as an antagonism between apocalyptic visions of modern civilisation versus renewal and rebirth of man.

Given that Expressionism was an urban movement, writers found opportunities to publish their texts or to present them at lectures and recitals associated with places such as Munich, Leipzig, Dresden, Vienna and, especially, Berlin, one of the fastest-growing cities of the time. Many key texts of Expressionism could first be read in the leading periodicals of the movement, such as Der Stürm, published by Herwarth Walden as a platform of aesthetic discussion, Franz Pfemferts’ politically oriented Die Aktion, or René Schickele’s Die weißen Blätter (The White Leaves).

The impact of modern technological warfare and the millions of dead on the battlefields of World War I (1914-1918), where many expressionist writers lost their lives, became central subjects of expressionist literature, giving rise to pacifist appeals and to the politically engaged messianic-activist Expressionism of the post-war years. With the rise of National Socialism in 1933, expressionist literature was banned, not to be rediscovered until after World War II, when texts were republished that have since become accepted as canonical, for example the poetry collection Menschheitsdämmerung (Dawn of Humanity, 1919; re-edited 1959).

The general decline of Expressionism by the mid-1920s was furthered by the implausibility and vagueness of the messianic stance (see for example the poems of Franz Werfel or Ludwig Rubiner) and the rise of new stylistic concepts (Dada, Neue Sachlichkeit).

Research from the last three decades has stressed the importance of gender themes in Expressionism and the role of female writers such as Henriette Hardenberg as well as the significance of lesser-known authors such as Hermann Kasack or Georg Kulka who were forgotten because their texts had not been included in the major anthologies of their time.

Expressionism and Architecture

Expressionist architecture is characterized by its use of expressive color and of both organic and crystalline shapes and lines. It is also marked by an interest in monumental and unbuildable structures. Expressionist architecture’s zenith came during and immediately after World War I, although some of the earlier works of architects such as Hans Poelzig (1869-1936) and Bruno Taut (1880-1938) are regarded as precursors (Sharp, 1966). In the years around 1910, Poelzig took inspiration from Gothic, Romanesque, and Baroque styles for his design of industrial and public buildings. The 1911 Water Tower in Poznan drew its expressiveness from technology (fig. 12).

The Water Tower’s construction of steel with brick and glass fillings, and its solid shape, anchoring it on the ground, created a monumental effect that celebrated industrial achievement and technology. Poelzig’s principles, which called for the use of restrained, sculptural shapes and a surface design where windows merge with walls, were also adhered to in his 1906 Werder mill in Breslau and the chemical works in Luban, 1911-1912 (fig. 13), but his best-known expressionist building was the Großes Schauspielhaus in Berlin (fig. 14) with a dramatic interior that was likened to a magic cave (Pehnt, 1979: 69-78).

Taut had also been an early protagonist of expressionist architecture, most notably with his 1914 Glass Pavilion—a temporary structure for the glass industry built at the Deutsche Werkbund exhibition in Cologne (fig. 15). Through his writings and architectural drawings, which appeared in publications such as in Der Weltbaumeister (The World Architect, 1920), Die Stadtkrone (The Crown of the City, 1919; see fig. 16), and Frühlicht (Early Light, 1920-1922), as well as in his role as city architect of Madgeburg, Taut became a lynch-pin for Expressionism (Washton Long, 1993, 122-139). Following the 1914 pavilion, Taut took inspiration from the poet Paul Scheerbart (1863-1915), whose rhymes and poems evoked visions of colorful castles, domes, buildings on mountaintops, and an architecture made of glass, as illustrated by Taut in Alpine Architecture (1919; fig. 17). These ideas fueled a German utopian spirit that had been gaining momentum since World War I, the abdication of Wilhelm II, and the establishment of the Weimar Republic. Architects saw themselves as demiurges of a new society and future.

Scheerbart’s Glasarchitektur in particular fuelled the belief of Taut, the architectural critic Adolf Behne (1885-1948), and (in 1919) the members of Die gläserne Kette (The Glass Chain), that the advent of a new "glass culture" would refine morality. Die gläserne Kette was an exchange of utopian letters and drawings initiated and organized by Taut. Disguized by pseudonyms, twelve artists and architects exchanged thoughts, visions, and drawings in a search for the roots of creativity, the origins of architecture, and the relationship between architecture and the cosmos. Among them were Hermann Finsterlin as ‘Prometh’ (fig. 18), Walter Gropius (1883-1969) as ‘Maß’, Wassili Luckhardt as ‘Zacken’ (fig. 19), and Hans Scharoun as "Hannes" (Whyte, 1985).

Social and educational reform and rejection of the city were essential parts of Taut’s ideology, and became apparent in his illustrated book Die Auflösung der Städte (The Dissolution of Cities, 1920) and Die Stadtkrone already mentioned above, which also drew on Garden City and socialist ideals. Social reform was also in the center of the program of the Arbeitsrat für Kunst (Working Council for Art) and Novembergruppe, both of which were organizations of Berlin artists with similar goals. They were among numerous revolutionary organizations initiated by workers and artists all over Germany to watch over the provisional government of November 1918. As early as Christmas 1918, the Arbeitsrat, whose spokesman was first Taut and then Gropius, published an architectural program and a manifesto that declared it to be the task of the artist to give the new state its appearance and to shape people’s experiences. Here, ideas of combining art and architecture to create a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), relating back to the 1914 Werkbund exhibition in Cologne, resurfaced in both publications. The majority of efforts by the Arbeitsrat related to architecture, demanding the abolition and replacement of established institutions such as building authorities, insisting upon an art for the people, and advocating the transformation of existing teaching systems (Washton Long, 1993: 191-209, 210-221 and Pehnt, 1979).

The idea of a Gesamtkunstwerk and the reformation of teaching institutions were also essential to the Bauhaus in Weimar in the years between 1919 and 1923. The Bauhaus program aimed to unify art and architecture, echoing the writings of the Arbeitsrat and Taut. Lyonel Feininger’s (1871-1956) 1919 woodcut in the manifesto (fig. 20), as well as his Sommerfeld Haus evoked the crystalline shapes symbolic of Expressionism (figs 21 and 22).

Among the most notable built examples of the movement are Erich Mendelsohn’s (1887-1953) Einstein Tower, built from 1920 to 1924 in Potsdam, and Peter Behrens’ (1868-1940) Hoechst Administration building (fig. 23), built within the same time-span in Frankfurt am Main.

Mendelsohn’s streamlined and sculptural design, which made the modestly sized building appear monumental, is an example of the organically shaped Expressionism that was also pursued by Hermann Finsterlin in his drawings for the "glass chain." Behrens, who had a successful office in Berlin and was artistic adviser to the Allgemeine Elektrizitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG) from 1907, adapted the dramatic use of color, shape, and space in Expressionism in his post-war work. In contrast to the formal and classical work before the war, this building did not adhere to the same rules of symmetry and serial arrangement as previously, but incorporated romantic and dramatic elements.

Related movements appear in the school of Amsterdam and Rudolf Steiner’s Goetheanum in Dornach, Switzerland, among others.

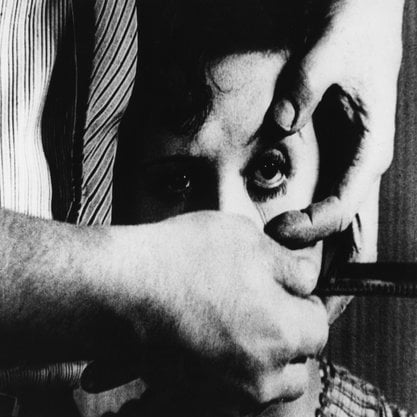

German Expressionist Film

Expressionist film emerged during the Weimar Republic era (1919-1933), and was most pronounced in a number of films from the early 1920s. The stylistic and thematic concerns of Expressionism are most fully on display in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919/20). Designed by key figures from expressionist painting and theater, Caligari’s highly stylized sets employ extreme angles, exaggerated proportions, and dizzying visual patterns. The film’s acting and the wild gesticulations of its twisted bodies lend a sense of the uncanny, while the low-key lighting and off-kilter cinematography gives one the feeling that the film obscures more than it reveals. These elements, in addition to its fantastical plot and macabre themes, make Caligari the archetypal expressionist film.

In the aftermath of World War I, as the laws and traditions of the Prussian monarchs gave way to newfound freedoms, much of German society was undergoing a sexual, artistic, and political reawakening. At the same time, the economic and bodily wreckage of the Great War had a profound impact on the German psyche. New ways of thinking, perceiving, and creating had to be devised. During this time, directors such as Fritz Lang, F. W. Murnau, Robert Wiene, Paul Leni, and Karl Heinz Martin drew inspiration from painting, literature, architecture, and theater associated with Expressionism, which sought to depict the internal and imaginative reality of things rather than their external, "objective" appearance. Expressionist filmmakers also sampled from German fairy tales and Gothic art to realise their fantastical worlds and the doppelgangers, monsters, madmen, and strange visitors to populate them.

In the vast majority of movies made before 1920, naturalism was the rule. Even illusionists like Georges Méliès relied upon frontal perspectives, realistic proportions, and generally stable spatio-temporal coordinates. German Expressionism arrived as the first major anti-realist movement in film. Beyond their extreme styles, these films depict stories within stories, performers and spectators, magic and confabulation, mirrors and doubles in a way that thematises spectacle itself, and reminds viewers that they are watching a film. Their overtly synthetic character has led some critics to accuse expressionist films of being "embarrassingly fake" (Arnheim, 1997), and others to see them as reflexive, ironic, and theatrical (Elsaesser, 1989, 2000, Telotte, 2006). Such a view of Expressionism as self-referential and purposefully unstable aligns it with the project of modernism generally. At the same time, there were undoubtedly economic, industrial, and ideological issues at play in the production of these films. Universum-Film Aktiengesellschaft (Ufa), originally intended by the government as a production studio for WWI-related propaganda, became a major player in Weimar cinema. Erich Pommer of Decla-Film (which eventually merged with Ufa) produced Caligari believing it could become both an artistic and box office success. His bet paid off, and Pommer went on to produce many classics of Expressionism’s heyday and its afterlife, including Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler (1922), Faust (1926), Metropolis (1927), and The Blue Angel (1930).

Two central books have emerged as integral to the conceptualisation and legacy of expressionist film: Lotte Eisner’s The Haunted Screen, and Siegfried Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler. Each of these books draws a conceptual link between expressionist cinema and the rise of National Socialism in its own way. Both Eisner and Kracauer were exiled German Jews writing in the decade following World War II, and it is important to bear this fact in mind when accounting for their views of expressionist cinema as a foreshadowing of Nazism. However much truth one might find in any claim about its historical premonitions, Expressionism undeniably anticipated and fundamentally shaped the future of cinema. Filmmakers such as Fritz Lang, Paul Leni, and Carl Freund fled Nazi Germany and found work in Hollywood, where they imported expressionist techniques into American cinema. The influence of Expressionism appears in the fundamental elements of genres such as film noir and horror, and reaches even further, into the films of Alfred Hitchcock and David Lynch, for instance, or the science fiction noirs Blade Runner (1982) and Dark City (1998).

Expressionism and Dance

In its relation to dance, Expressionism must be approached through diverse but related histories in the realms of theater, dance, and the visual arts. These histories trace a tendency from the nineteenth century through the 1930s toward the exploration of movement and gesture as a primary language and communicator of inner life. Within this history emerged the practice of free, absolute or new dance, and by the mid-1920s, a broad-based movement called, among other terms, modern dance, new artistic dance, and Tanzkunst (‘dance art’). Expressionism in dance is largely associated with the years 1911 to 1936 and the work in Switzerland and Germany of its primary theorist, Rudolf Laban, and choreographer Mary Wigman. This periodisation contrasts with the art-historical designation of German Expressionism as a movement in the visual arts from 1905 to 1920 associated with the activity surrounding the Bridge group (Künstlergruppe Brücke) in Dresden, The Blue Rider group (Der Blaue Reiter) in Munich and the journal and gallery Der Sturm in Berlin. In fact, the dance and art-historical histories are deeply entwined. Expressionist artists Emile Nolde and Ernst-Ludwig Kirchner were aware of the dance of their time and created works of art in which dance appears as a mark of Expressionism’s more general aspiration to link subjective experience with more eternal humanity and nature. In Vasily Kandinsky‘s The Yellow Sound, written for theater in 1909, dance figures as a compositional synthesis of line, color, and time. Expressionist practitioners in both art and dance emphasized shared inner necessity and eternal principles over form, and helped forge the watershed modernist development of abstraction. As Expressionism in dance focused on reaching absolute expression free of music, the individual body’s significance was replaced by movement, and the representation of external form and narrative shifted to abstract gesture and intuited meaning. For expressionist painters, dance was a model for how the individual self might communicate universal or absolute content.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, the teachings of French musician François Delsarte spread among practitioners of music, theater, and dance. For Delsarte, movement and gesture were the link between life, soul, and spirit, and the most direct communicators of emotional truth. By embracing Delsartian concepts of emotive movement based in the body’s natural form, weight, and connection to nature, dance reformers such as Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis serve as early examples of the expressionist impulse in dance. The impulse also took root from early-twentieth-century German body culture and the life reform movement. In Hellerau, Émile Jaques-Dalcroze’s school of music, founded in 1910, trained students in rhythmic gymnastics, using movement to externalise intuitive sensations of harmony. Wigman and Suzanne Perrottet, Laban’s primary collaborators in forging the new dance, were trained teachers of the Dalcroze method called eurhythmics and hence integrated ideas and methods from eurhythmics into expressionist dance pedagogy. Wilhelm Worringer’s widely read psychological text Abstraction and Empathy (1909) also provided Expressionism with a treatise on shared artistic volition and a justification of abstract form as the expression of individual psychic or spiritual states.

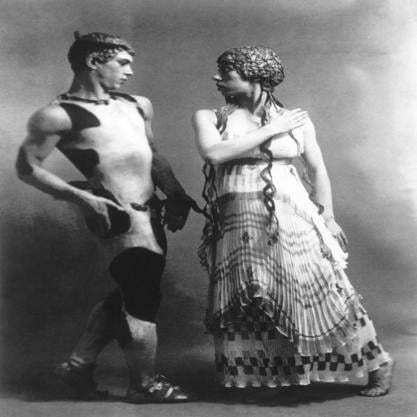

While Mary Wigman’s Dalcroze training at Hellerau from 1911 to 1913 introduced her to early expressionist Brücke artists in nearby Dresden, Rudolf Laban began teaching dance in 1910 within the fabled modernist milieu of Schwabing in Munich during the years of the Blaue Reiter group. A painter himself, Laban admired the innovations of Kandinsky as well as the dancing of Clotilde and Alexander Sakharoff. From 1913 to 1917 Laban ran his school from the utopian community on Monte Verità near Ascona, Switzerland. Wigman joined him there in 1913 on the painter Nolde’s recommendation (see figs 24 and 25). In Ascona, Laban and his followers developed the theories and eventually the notation for a new dance. Promoting gymnastics, a vegetarian diet, freedom of dress, and connectedness to nature and the cosmos, Laban trained amateur dancers as ‘movement choirs,’ a movement practice designed to create community rituals. Asserting dance’s autonomy from the other arts and its role as the unifier of emotion, intellect, and spirit, Laban and Wigman’s dancers often performed in masks to the spare sounds of percussion, with movement invoking Dionysian associations of the ecstatic and grotesque. As with expressionist literature, visual art, and architecture, expressionist dance was greatly influenced by the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche, who gave to dance the role of uniting man and nature. Nietzsche’s study of Greek tragedy also set up the new dance’s interest in choric movement and antiquity as a model for harmony between civilisation and spiritual life.

In the years after World War I, Laban’s followers opened dozens of schools across Europe, and Wigman established a central school in Dresden and branch schools in other major German cities. Both Wigman and Laban toured extensively and their schools produced many of the most well-known dancers of the interwar period, including Wigman’s students Gret Palucca and Harald Kreutzberg, and the Laban-trained Kurt Jooss. Three Dance Congresses held in Germany between 1927 and 1930 gave Laban and Wigman a pulpit to promote the establishment of a German Dance Academy, and allowed for wide-ranging discussion on the new modern dance movement, later known as Ausdruckstanz. The movement may be generally conceived as a proprioceptive or kinesthetic experience of both dancer and viewer, and as the abstract form of psychological interiority. Laban and Wigman taught movement based in natural states of tension and relaxation, involving an intuitive use of the entire body from head to fingers. As an example of expressionist choreography, Wigman’s second version of Witch Dance (Hexentanz) from 1926, filmed in 1930, shows the dancer stomping and clawing the air with sharp gestures; low and hunched, she seems to be following possessed inner impulses. Her mask and tightly woven and patterned robe separate her body in time and space to suggest pure physicality and emotion. Other dancers associated with Expressionism include the cabaret performers Valeska Gert and Niddy Impekoven and concert dancers Berthe Trümpy and Yvonne Georgi.

Dance Expressionism complicates the history of avant-garde radicalism because of the movement’s alliance with, and co-optation by, Adolf Hitler’s regime. Under the National Socialist state from 1933 to 1945, Ausdruckstanz became known simply as "German Dance." The folk aspect of Laban’s movement choirs translated easily to the National Socialist Party’s völkisch pretentions, and Laban organized a festival of "German dance" as part of the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games: Wigman, Palucca and Kreutzberg all participated. By the end of the regime, however, all these artists had been sidelined, as Nazi cultural politics looked to other forms of dance and movement culture as more effective forms of "invisible propaganda" (Goebbels’s term).

In the 1970s and 1980s, as German visual artists revisited expressionist painting as a source for painterly innovation, so too did German choreographers, notably Pina Bausch, revisit the work of her mentor Kurt Jooss and his generation of Ausdruckstanz artists. Working between dance and theater, Bausch and her cohort gave a new meaning to a term first used by Jooss in 1928—Tanztheater (dance theater).

Key Works

Further Reading

Albrecht Schröder, Klaus (2005) Egon Schiele (Exhibition catalogue), Munich: Albertina and Prestel Verlag.

Anz, Thomas (2002) Literatur des Expressionismus (Expressionist Literature), Stuttgart: Metzler.

Arnheim, R. (1997) Film Essays and Criticism, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Balázs, B. and E. Carter (2011) Béla Balázs: Early Film Theory: Visible Man and The Spirit of Film, New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Barron, S. (1997) German Expressionism: Art and Society, New York: Rizzoli.

Bartelik, Marek (2005) Early Polish Modern Art. Unity in Multiplicity, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Benson, T. (2001) Expressionist Utopias: Paradise, Metropolis, Architectural Fantasy, Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Benson, T. O. (1994) Expressionist Utopias: Paradise, Metropolis, Architectural Fantasy, Berkeley: Berkeley: University of California Press.

Benson, Timothy O. (ed.) (2002) Central European Avant-Gardes: Exchange and Transformation, 1910-1930, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Bogner, Ralf Georg (2005) Einführung in die Literatur des Expressionismus (Introduction to Expressionist Literature), Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

Brandstätter, Christian (ed.) (2006) Vienna 1900 and the Heroes of Modernism, London: Thames & Hudson, Ltd. and Vendome Press.

Coates, P. (1991) The Gorgon's Gaze: German Cinema, Expressionism, and the Image of Horror, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dabrowski, Magdalena (ed.) (2009) Egon Schiele: The Leopold Collection, Vienna, Munich: Prestel.

Donahue, Neil H. (ed.) (2005) A Companion to the Literature of German Expressionism, Columbia, SC: Camden House.

Eisner, L. H. (1969) The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Elsaesser, T. (1989) German Expressionist Prints and Drawings, The Robert Gore Rifkind Center for German Expressionist Studies, Vol. 2, Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Elsaesser, T. (2000) Weimar Cinema and After: Germany's Historical Imaginary, New York: Routledge.

Głuchowska, Lidia (2012) ‘Polish and Polish-Jewish Modern and Avant-Garde Artists in the "Capital of the United States of Europe" c. 1910-1930’, Centropa, September.

Gordon, D. E. (1987) Expressionism. Art and Idea, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Herbert, B. (1983) German Expressionism: Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter, London: Jupiter Books.

Howe, Dianne S. (1996) Individuality and Expression: The Aesthetics of the New German Dance, 1908-1936, New York: Peter Lang.

Junge, H. (1992) Avantgarde und Publikum: Zur Rezeption avantgardistischer Kunst in Deutschland 1905-1933 (Avantgarde and the Public: The Reception of avantgarde art in Germany 1905-1933), Cologne and Vienna: Böhlau.

Kaes, A. (2009) Shell Shock Cinema: Weimar Culture and the Wounds of War, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kandinsky, W. (1911) Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Concerning the Spiritual in Art), München.

Kracauer, S. (1947) From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Launay, Isabelle (1996) À la recherche d’une danse moderne: Rudolf Laban, Mary Wigman (Searching for Modern Dance: Rudolf Laban, Mary Wigman), Paris: Chiron.

Lloyd, J. (1991) German Expressionism: Primitivism and Modernity, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Lloyd, Jill (ed.) (2006) Van Gogh and Expressionism, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

Long, R-C W. (ed.) (1993; 1995) German Expressionism: Documents from the End of the Wilhelmine Empire to the Rise of National Socialism, New York: G.K. Hall; Berkeley: University of California Press.

Łukaszewicz, Piotr and Jerzy Malinowski (1980) Ekspresjonizm w sztuce polskiej (Expressionism in Polish Art), Wroclaw: Muzeum Narodowe.

Macel, Christine and Emma Lavigne (eds.) (2011) Danser sa vie: Art et danse de 1900 à nos jours (Dancing on'es Life: Art and Dance from 1900 to Present), Paris: Éditions du center Pompidou.

Manning, Susan (2006) Ecstasy and the Demon: the Dances of Mary Wigman, Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press.

Wigman, Mary MoMA (1926) ‘Hexentanz (Witch Dance) Version 2’, Inventing Abstration: 1910-1925, http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2012/inventingabstraction/?work=238 (accessed March 18, 2015).

MoMA ‘Two Dances Choreographed by Rudolf von Laban, before 1925’, Inventing Abstraction 1910-1925, http://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2012/inventingabstraction/?work=237 (accessed March 18, 2015).

Murphy, Richard (1999) Theorizing the Avant-Garde: Modernism, Expressionism, and the Problem of Postmodernity, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Natter, Tobias G. (ed.) (2002) Oskar Kokoschka: Early Portraits from Vienna and Berlin, 1909-1914, DuMont Verlag and the Neue Galerie New York.

Keilson, Ana Isabel , An Paenhuysen and Wolfgang Muller (2012) 'Curating Valeska Gert: Ana Isabel Keilson in onversation with Wolfgang Muller and An Paenhuysen', Critical Correspondence: the Movement Research Journal, http://www.movementresearch.org/criticalcorrespondence/blog/?p=4378 (accessed May 5, 2016).

Partsch-Bergsohn, Isa and Harold Bergsohn (2003) The Makers of Modern Dance in Germany: Rudolf Laban, Mary Wigman, Kurt Jooss, Princeton, NJ: Princeton Book Co..

Preston-Dunlop, Valerie M. (1998) Rudolf Laban: an Extraordinary Life, London: Dance Books.

Pehnt, W. (1979) Expressionist Architecture, London: Thames and Hudson.

Pehnt, W. (1985) Expressionist Architecture in Drawings, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Prange, R. (1991) Das Kristalline als Kunstsymbol: Bruno Taut und Paul Klee. Zur Reflexion des Abstrakten in Kunst und Kunsttheorie der Moderne (The Crystalline as Artistic Symbol. Bruno Taut and Paul Klee. Reflecting on the Abstract in Modern Art and Art Theory), Hildesheim: Olms.

Raabe, P. (1964) Die Zeitschriften und Sammlungen des literarischen Expressionismus (Journals and Collections of Literary Expressionism), Stuttgart: J. B. Metzlersche Verlag.

Raabe, P. (1972) Index Expressionismus (Index of Expressionism), 18 volumes, Liechtenstein: Kraus Thomson.

Ratajczak, Józef (ed.) (1897) Krzyk i ekstaza. Antologia polskiego ekspresjonizmu (Scream and Ecstasy: Anthology of Polish Expressionism), Poznan: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie.

Schroder, Klaus Albrecht and Johann Winkler (eds.) (1991) Oskar Kokoschka, Munich: Prestel.

Sharp, D. (1966) Modern Architecture and Expressionism, London: Longmans.

Snyder, Allegra Fuller (1991) Mary Wigman, 1886-1973: "When the Fire Dances between Two Poles, Pennington: Princeton Book Co., Dance Horizons.

Steffen, Barbara (ed.) (2011) Vienna 1900: Klimt, Schiele, and their Times, A Total Work of Art, Ostfildern: Fondation Beyeler and Hatje Cantz Verlag.

Telotte, J. P. (2006) 'German Expressionism: A Cinematic/Cultural Problem,' in L. Badley, B. Palemr and S. J. Schneider (eds) Traditions in World Cinema, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 15--28.

Vergo, Peter (1981) Art in Vienna 1898-1918: Klimt, Kokoschka, Schiele and their Contemporaries, London: Phaidon.

Vietta, Silvio (1975) Hans-Georg Kemper Expressionismus, Munich: Fink.

Waissenberger, Robert (ed.) (1984) Vienna 1890-1920, New York: Rizzoli.

Washton Long, R.-C. (1993) German Expressionism. Documents from the End of the Wilhelmine Empire to the Rise of National Socialism, Toronto: Maxwell Macmillan.

Weikop, C. (ed.) (2011) New Perspectives on Brücke Expressionism: Bridging History, Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate.

West, S. (2000) The Visual Arts in Germany 1890-1937: Utopia and Despair, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Whyte, I. B. (ed.) (1985) Crystal Chain Letters: Architectural Fantasies by Bruno Taut and His Circle, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Wollenberg, H. H. (1972) Fifty Years of German Film, New York: Arno Press.

Worringer, W. (1908; 1953) Abstraktion und Einfühlung. Ein Beitrag zur Stilpsychologie, trans. M. Bullock as Abstraction and Empathy: A Contribution to the Psychology of Style, with Intro. by H. Kramer, Chicago: Elephant Books.