Overview

Abstract Expressionism By Toteva, Maia; Legaspi Ramirez, Eileen; Rosenbaum, Roman; Toteva, Maia; Legaspi Ramirez, Eileen; Rosenbaum, Roman

Overview

Abstract Expressionism

Abstract Expressionism was a movement initiated by a group of loosely affiliated artists that came together during the early 1940s, primarily in New York City. Artists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Lee Krasner, among others, pursued radically new forms to express a deep sense of meaning through their painting. Flourishing during the 1940s and the 1950s, Abstract Expressionism gained recognition as the first specifically American movement to achieve an international reputation. Increased interest in abstract expressionist artists placed New York at the center of the art world, a position previously reserved for Paris. Since most first-generation abstract expressionists lived in New York City, the movement was also known as ‘‘The New York School.’’ While the critics Harold Rosenberg and Clement Greenberg preferred the names ‘‘action painting,’’ ‘‘American-type Painting,’’ and ‘‘painterly abstraction,’’ the term ‘‘abstract expressionism’’ emerged in Germany in 1919 in reference to German Expressionism. Alfred Barr used it for the first time in the United States in 1929 to describe the paintings of Vasily Kandinsky. In 1946, Robert Coates adopted the term to designate contemporary American painting, describing Hans Hofmann as representative ‘‘of what some people call the spatter-and-daub school of painting and I [Coates]…have christened abstract expressionism.’’ The phrase served to unite the two dominant aspects of abstract expressionist art: a non-figurative commitment that reduced representational objects to basic geometric forms (abstraction) and the improvisational brushstrokes expressing emotion or conceptual states (expressionism). Despite the fact that most abstract expressionists rejected labels, the term endured.

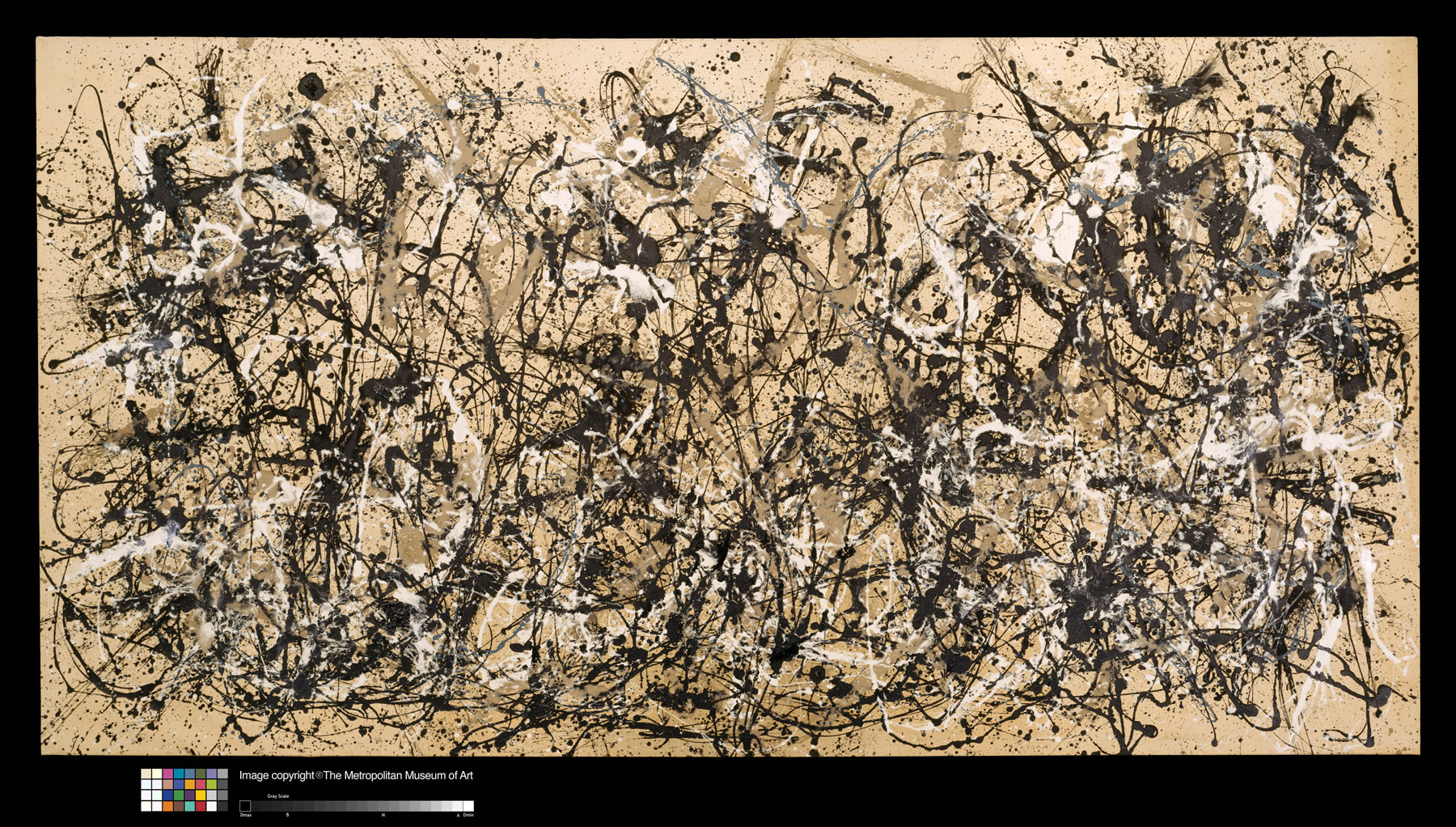

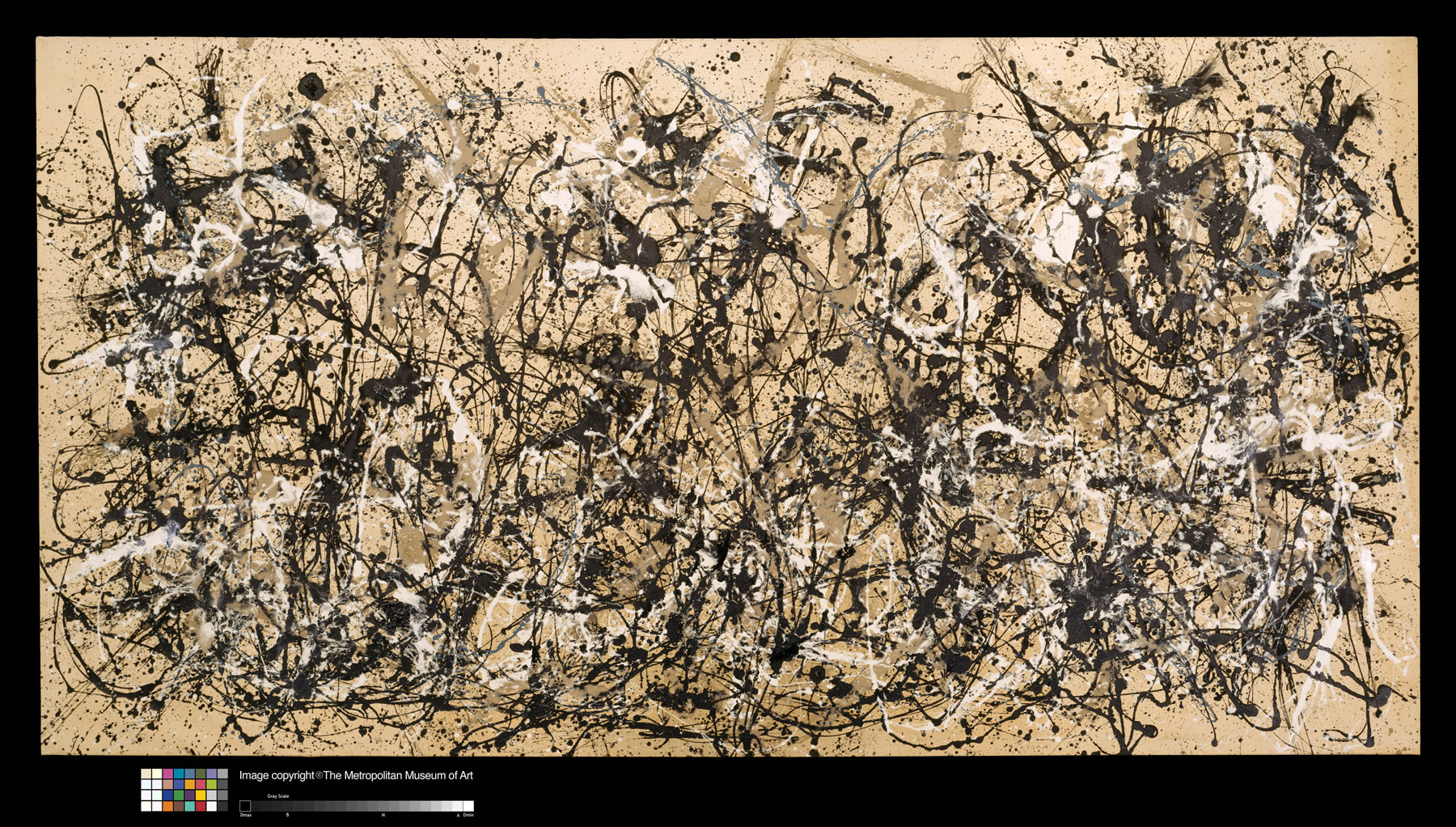

Never a formal affiliation, Abstract Expressionism encompasses a variety of styles and represents an artistic attitude rather than a single form of expression. What unites the distinct personalities within the movement is their rejection of overt political messages, a desire to express emotional and spiritual truths, and a search for universal or morally significant themes often implemented on a grand scale. Not all works were abstract and emotionally expressive; however, all abstract expressionists valued what was termed ‘‘authentic individuality’’ and improvisation. Emblematic of their approach are the incorporation of chance and accidents that occur during the painting process, a tendency towards ‘‘all-over’’ compositions in which all parts of the canvas are of equal value, an emphasis on the process or act of painting used as a means of communication, and a focus on the surface of the canvas where loose strokes, gestural marks, or planes of color convey expression. A commitment to truthfulness, emotion, and profound themes unites diverse artistic approaches ranging from the calligraphic, poured and dripped paintings of Jackson Pollock to the soft-edged and meditative rectangles of Mark Rothko.

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation ARS, NY and DACS, London 2016.

Based on trends within the movement, Abstract Expressionism came to be divided into two groups: gestural (action) painting and color field painting. Gestural painting includes techniques that use pronounced, often energetic, brushstrokes as a way of expression, such as pouring and dripping thinned paint onto a raw canvas laid on the ground (Pollock) or dynamic gestures articulating powerful iconic figures and abstract imagery (De Kooning, Franz Kline, and Lee Krasner). Color field painting emphasizes the lyrical effects and expressive capacities of Color—often poured or stained directly onto the canvas—to convey a vision of the ‘‘sublime’’ or achieve a cerebral and reflective state of mind. The latter group encompasses methods such as the quiescent, intensely coloured landscape-like fields of Mark Rothko or the vast areas of unmodulated, flat, and stained colour of Barnett Newman, Helen Frankenthaler, Kenneth Noland, and Clyfford Still.

Most abstract expressionists began working in the 1930s, so the Great Depression and its aftermath are paramount to understanding their artistic choices. Many met through government relief programs such as the depression-era WPA (Works Progress Administration), which employed artists to paint murals in public spaces. Although the experience encouraged future abstract expressionists to paint on a large scale, artists abandoned the popular movements of the time—regionalism and socialist realism—and their corresponding ideologies (nationalism and socialism) in search of universal art free of totalitarian gist, overt politics, and provincialism. In the eyes of post-war and Cold War audiences, Abstract Expressionism voiced the inner turmoil and dark mood of the time and embodied the American spirit—monumental, romantic, and symbolic of individual freedom. At the same time, the artists developed a sense of community—redolent of a common philosophy and call to social responsibility—as they frequented various locales in New York City to engage each other’s work and discuss topics such as existentialism, ‘‘gestalt therapy,’’ and Zen Buddhism.

Among various post-war factors, it was the vibrant New York art scene and the assimilation of European modernism that set the stage for Abstract Expressionism’s break from traditional painting. American artists encountered manifestations of European modernism, particularly Surrealism, Cubism, Dada, and Geometric Abstraction in the galleries of an expanding network of museums such as the Museum of Modern Art and newly established galleries, such as Peggy Guggenheim’s The Art of this Century gallery. The abstract expressionists’ primary source of inspiration, however, came with the influx of expatriate artists including Marcel Duchamp, André Masson, and Piet Mondrian who crossed the ocean to escape Hitler-dominated Europe. Abstract Expressionism benefited particularly from direct contact with Surrealism (Max Ernst), De Stijl (Mondrian), and artistic philosophies concerned with the physicality of paint and the possibilities of abstraction (Hans Hofmann and Arshile Gorky). Surrealism impacted Abstract Expressionism with its interest in the psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, as well as its incorporation of chance, improvisation, and use of automatism to tap into one’s subconscious.

In addition to the above-mentioned male artists, Abstract Expressionism included notable women such as Lee Krasner, Hedda Sterne, Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, and Louise Bourgeois.

Abstract Expressionism in the Philippines

Abstract Expressionism in the Philippines developed in tandem with many post-World War II movements that grew out of a desire to remain current with international artistic trends. Increased access to Western state grants and educational opportunities in the Philippines’ former colonizing power, the United States, brought the American movement to the Philippines where many of the country’s artists returned after receiving an American education. Two notable Filipino abstract expressionist artists, José Joya (1931–1995) and Lee Aguinaldo (1933–2007) studied at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan and the Culver Military Academy in Indiana respectively.

Despite the rise of abstract expressionist art in the Philippines, the Filipino audience was not very receptive to Abstract Expressionism. It perceived abstraction as failed mimetic representation, and the public attitude towards abstract art was characterized by indifference or outright antagonism, even during the 1970s as the Philippine art market began to open up to abstraction. However, while abstraction was regarded as purely decorative in some circles, it was seen as cerebral in others. In examining intersections between modern-contemporary expression and pre-colonial visual languages, some critics have argued that abstraction demonstrates affinities with forms present in textile and mat weaving from both Northern and Southern upland and riverine ethnolinguistic communities, as well as in the architecture, dress patterns, metal work and woodcraft of Muslim and Lumad communities in Mindanao.

José Joya was an important figure in the development of Abstract Expressionism in the Philippines who had significant influence over successive generations of abstract expressionist painters through his dedication to teaching, especially at the University of the Philippines College of Fine Arts. Joya’s teaching post allowed him to expand his network outside Manila, specifically through the Visayas (via University of the Philippines Cebu College for instance). Other key artist-art-educators from the Philippines include Florencio Concepcion and Constancio Bernardo. Fernando Zobel was a much earlier artist-art-educator who similarly brought the influence of Western Abstract Expressionism to the Philippines where he returned shortly after graduating from Harvard University in 1949. Zobel eventually settled in Spain where he established the Museum of Spanish Abstract Art in Cuenca. However, before migrating to Spain, he bequeathed his seminal collection of early Philippine modernist art to the Ateneo Art Gallery and nurtured a progeny of modernist advocate-critics including Emmanuel Torres and Leonidas Benesa.

One key point of divergence between Philippine Abstract Expressionism and its American counterpart is the former’s casual regard for gestural painting. Unlike much of the debate that surrounds the work of Northern American abstract expressionist artists, particularly Jackson Pollock who has been propped up as the epitome of creative spontaneity, very little critical attention has been paid to how Philippine Abstract Expressionism seemed unburdened by the desire to draw from primal impulses, how in effect, the artists’ work was undertaken in a more calculated manner. Benesa, a key Filipino modernist critic describing Joya states: ‘‘A number of the drawings and sketches in the mid-sixties show that, however spontaneous and expressionistic the gestures of the artist may appear in the final work, in the tradition of action painting, they have been rehearsed beforehand through the various disciplines of linear melody and tonal rhythm.’’ Despite his inclination toward premeditation, Joya is still generally upheld as representative of his generation of Philippine abstractionists, as he eventually underwent a degree of stylistic liberation. Critics suggest Joya’s stylistic shift is evidenced in the diminished ‘‘stiffness in his drawing hand,’’ which appears following his departure from the Philippines to pursue further studies in Europe and the United States.

Substantial anthropological and cultural scholarship has critically examined whether global pockets of Abstract Expressionism are merely derivative of American Abstract Expressionism. These critical accounts have pointed out that Abstract Expressionism has become enfolded into a canon of art history subjecting it to accounts of one-way transfer from the West to other parts of the world. It is this assertion, encumbered with the postcolonial thrust to establish national identity, which appears to have persuaded artists including Joya to modify their approach to abstraction. However, prominent Western abstract expressionist artists have expressed a debt to Asian calligraphic scroll painting, though arguably in a mitigated sense.

Abstract Expressionism in Japan, (抽象表現主義, chūshō hyōgenshugi)

Abstract Expressionism emerged in Japan in 1954 at the end of the American Occupation, and only nine years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki, when a group of seventeen artists living in Osaka founded the Gutai (具体, embodiment) artists association. More than any other group in Japan, the Gutai artists considered and engaged with Abstract Expressionism, particularly the works of Jackson Pollock. Arguably one of the most successful Japanese disciples of American Abstract Expressionism was Okada Kenzō, who migrated to the United States in the 1950s and made a name for himself by using the decorative effects of traditional Japanese paintings in his works. Just as the Japanese artistic Diaspora had infused Abstract Expressionism with their alterity in New York, American Expressionism made appearances in Japan through Gutai artists, whose derivative abstract-expressionist paintings constituted the rebellions of a younger generation of artists against a society responsible for the destruction that occurred during the war. The post-war Japanese assimilation of Western institutions and values is often described as a knee-jerk reaction against Japanese militarism and a means of expressing the freedom of the newly embraced democratic reforms.

An international offshoot of the American post-World War II graphic art movement, Japanese Abstract Expressionism developed into a globally pervasive force throughout the 1950s. During this period, a large vanguard of Japanese artists relocated to the United States, including Hasegawa Saburō (長谷川三郎), Inokuma Gen’ichirō (猪熊弦一郎), Kawabata Minoru (川端実), Masatoyo Kishi (政豊岸), Niizuma Minoru (新妻実), Okada Kenzō (岡田謙三), Teiji Takai (伊藤ていじ), and James Hiroshi Suzuki.

Abstract Expressionism has also been identified as a politically motivated articulation of American identity in the Post-World War II world. In this sense the radical native Gutai and Japanese influence on Abstract Expressionism in the United States was regarded as evidence of the imperialistic success of the American way in the Asia-Pacific region.

Despite the fact that Asian and in particular Japanese influences on Abstract Expressionism were tenuous, the internalization of ‘‘oriental thought’’ and especially Zen was an important ingredient in juxtaposing nationalistic American aesthetic trends in opposition to European art, after the successful defeat of Japan in the Asia-Pacific theater.