Overview

Dance By Lindgren, Allana C.

Overview

Historically, modern dance scholarship has followed the contours of the field as defined by John Martin, the revered dance critic for The New York Times, who used the phrase “modern dance” to characterize performances by early progenitors such as Isadora Duncan and Ruth St. Denis, as well as by the leading proponents of innovative concert dance choreography, including Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Hanya Holm, and Charles Weidman.

While the dance entries in the Routledge Encyclopedia of Modernism (REM) offer new insights about these artists and others traditionally associated with modernism, scholars are now also rethinking definitions, and the temporal and geographical parameters that previously limited modernist dance activities to the salons, cabarets, and concert stages of Europe and the United States.

Embracing habitually excluded types of dance such as social dance as well as pursuing a global history of modernist dance practices provides an opportunity for large-scale themes to emerge. Most notably, the aggregate of dance scholarship in the REM suggests that modernist dance practices resist a singular origin narrative, while at the same time showing how modern dance artists from around the world and across time consistently experimented with new dance ideas that served as embodied responses to the processes of modernization and the conditions of modernity. Notably, dancing bodies were often sites of contention in the construction and enactment of modern subjectivity. Ideas about social decorum, for instance, were asserted through modern ballroom dances and in the pages of dance manuals such as The Modern Dance Tutor; or, Society Dancing (1878), which was written by Canadian dance teacher John Freedman Davis. Conversely, for commentators including W.C. Wilkinson, a US clergyman and author of the anti-dance treatise The Dance of Modern Society (1869), the new couples dances implied social degeneration.

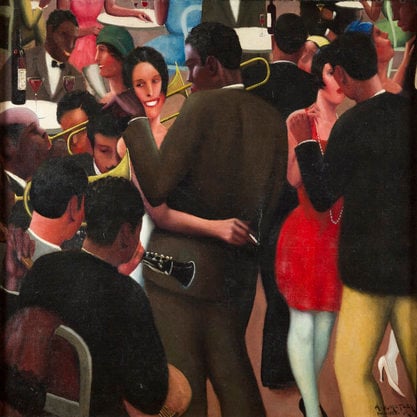

Beginning in the 1890s, ragtime music and dances brought racial and generational tensions to the fore. Born in the jook houses of the Southern United States, and associated with African-American culture and syncopated rhythms, the spirited couples steps of ragtime dances were the epitome of modernity for many white youth, but morally suspect to their elders.

Dance became a form of resistance when African-American dancers such as Bill ‘Bojangles’ Robinson as well as the Nicholas Brothers refuted race-based prejudice through their virtuosic tap dance performances or when choreographers like Katherine Dunham, Pearl Primus, Eleo Pomare, or Alvin Ailey repudiated racial discrimination or celebrated African heritage and African-American cultural experiences in their dances.

Gender also repeatedly appears in discussions about dance and modernism. Loie Fuller, Badī’ah Masābnī, Dai Ailian, Germaine Acogny, Chandralekha – woman across the globe not only challenged orthodox perceptions about dance, but embodied new ideas about what it meant to be a modern woman through their artistic leadership. Men also contested gender stereotypes. In the 1930s, for instance, Ted Shawn founded an all-male dance company and redefined athletic male beauty while working to validate the presence of men on concert dance stages.

The use of dance as a forum for overtly political debate recurs within the context of modernism regardless of locale. In particular, during the 1930s several US organizations, including the New Dance Group and the Workers Dance League, used dance to promote leftist ideals in choreographic works such as Sophie Maslow’s Dust Bowl Ballads (1941). In China, Wu Xiaobang, “the father of Chinese new dance,” studied Western dance styles in Japan and was the first Chinese citizen to establish a modern dance studio in the early 1930s before becoming a member of the National Salvation movement in 1937 and using dance as a form of activism in choreographic works including Poppy Flower, an anti-fascist dance-drama he created in 1939.

Beyond parallel interests in the socio-political efficacy of dance practiced by artists in different regions and countries, one of the most distinct themes of modern dance in the global context is the prevalence of transnational engagement. The international movement of dance artists, teachers, and audience members enabled the transmission of new ideas, which were sometimes adopted, sometimes adapted, and sometimes fervently rejected in ways that inspired oppositional expression. In short, the world history of modern dance asserts that there are no nationally “pure” art forms.

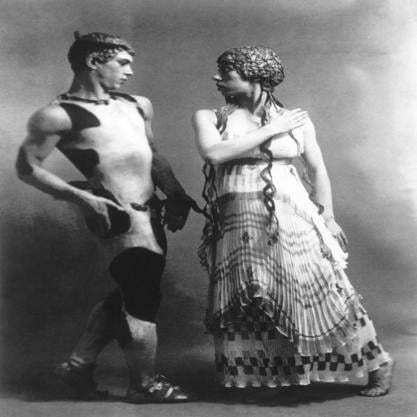

Transnational collaboration sometimes occurred when artists were gathered to contribute to a specific production. Serge Diaghilev, the founder of the Ballets Russes, assembled teams of artists of different nationalities to create innovative and interdisciplinary productions for his company. The Ballets Russes’s production of Parade (1917) featured a libretto by French writer Jean Cocteau that was set to music by French composer Erik Satie. Guillaume Apollinaire, an Italian-born French writer, provided a programme note. Léonide Massine, the choreographer, and the principal dancers, were Russian. The Spanish artist Pablo Picasso designed the set, costumes, and curtain.

Dance styles and techniques were particularly mobile. Ausdruckstanz emphasized the capacity of movement to generate and convey emotion in Rudolf Laban’s movement choirs as well as in individualized approaches to creation as exemplified by Mary Wigman’s structured improvisations and choreography. This German version of modern dance exerted a global influence before it was co-opted by the Nazis. In the United States, Graham developed a pedagogical and choreographic style based on the concepts of contraction and release. Graham’s distinctive and innovative technique gained followers around the world and has been used as a foundational vocabulary by several modern dance companies, including the Toronto Dance Theatre.

At times, zones of contact led to appropriation or the perpetuation of discriminatory and colonist perspectives as exemplified by European writers, including Gustave Flaubert and Colette, who visited the Middle East during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and re-enforced Orientalist beliefs in their sexualized depictions of the dancers.

At other moments, however, non-Western artists co-opted and adapted the new ideas they encountered. Often the imported movement techniques were kept and combined with local, regional, or national stories and themes. As a result, transnational contact regularly sparked artistic hybridity. Ishii Baku, one of the first Japanese modern dance artists to study in the West, was influenced by the ideas he encountered at Émile Jaques-Dalcroze’s school. He was similarly intrigued by the Ausdruckztanz choreography of Wigman and Harald Kreutzberg. After creating the first modern dance school in Japan, he developed his own pedagogical methodology that used Jaques-Dalcroze’s Eurhythmics as a foundation. In turn, Ishii exerted his own international influence. Shinmuyong, a Korean form of creative dance, was the result of a number of sources, including Ausdruckstanz, which entered Korea in the mid-1920s when Ishii toured Korea. Several students followed him back to Japan in order to further their training in Western dance. One of Ishii’s students, Ch’oe Sŭng-hŭi, created choreographic works that combined aspects of Dalcroze Eurhythmics, Ausdruckztanz, and traditional Korean dance, among other influences, to make a distinctly Korean modern dance form.

The flow of transnational influence was often multi-directional. For instance, Eastern artists affected the practices of Western artists. Ito Michio, who had studied Eurhythmics in Hellerau, worked with W.B. Yeats and Ezra Pound to create the dance-drama At the Hawk’s Well (1916). Touring provided particularly important opportunities for intercultural projects. Anna Pavlova and Uday Shankar co-created and performed in two dances – Krishna and Radha and Hindu Wedding – that were included in Pavlova’s production Oriental Impressions (1923).

Paradoxically, transnationalism was frequently transposed and naturalized for nationalistic purposes. In the 1930s, for instance, sisters Nellie and Gloria Campobello assisted in the Mexican government’s attempts to create a national culture that reflected its revolutionary ambitions by merging European dance styles, including ballet, with aesthetic elements associated with Mexico’s indigenous peoples.

Certainly all of the artistic motivations and creativity associated with modern dance is not possible to encapsulate within this limited overview. Yet, even a brief introduction to the entries in the REM suggests that an expansive and global perspective is needed to begin to understand the true depth, range, and significance of dance as a modernist art.