Overview

Cubism [REVISED AND EXPANDED] By Kolokytha, Chara

Overview

Abstract

Cubism is an art movement that emerged in Paris during the first decade of the 20th century. It was a key movement in the birth and development of non-representational art. The term was established by Parisian art critics, derived from Louis Vauxcelles, and possibly Henri Matisse’s description of Georges Braque’s reductive style in paintings of 1908. It soon became a commonplace term and was widely used to describe the formalist innovations in painting pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Braque from 1907 to 1914.

Influenced by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, artists such as Fernand Léger (Les Fumeurs, 1912), Juan Gris (Grapes, 1913) and Robert Delaunay (Windows, 1912) developed their own distinctive cubist styles. They introduced new ways of working with colour, geometry, and elements of abstraction (Léger, Contraste de formes, 1913). Alternative cubist perspectives were also introduced by painters such as Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier, Roger de La Fresnaye, André Lhote, and sculptors such as Jacques Lipchitz and Henri Laurens. Cubism’s influence was not limited to painting and sculpture but extended to architecture, poetry, music, literature, and the applied arts.

Cubism is an art movement that emerged in Paris during the first decade of the 20th century. It was a key movement in the birth and development of non-representational art. The term was established by Parisian art critics, derived from Louis Vauxcelles, and possibly Henri Matisse’s description of Braque’s reductive style in paintings of 1908. It soon became a commonplace term and was widely used to describe the formalist innovations in painting pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque from 1907 to 1914.

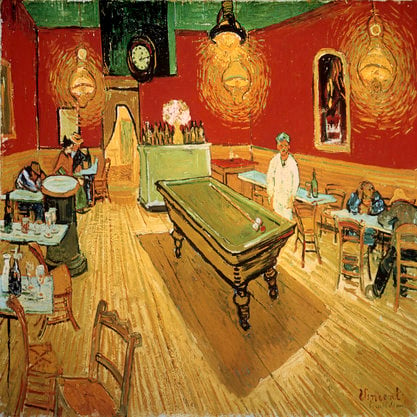

Source: New York, Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Oil on canvas, 8' x 7' 8 (243.9 x 233.7 cm). Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest. 333.1939 © 2016. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence.

Cubism signals the break with Renaissance tradition through the rejection of three-dimensional illusionist composition. The nearly monochromatic palette (Picasso, Still Life with a Bottle of Rum, 1911) of early cubist painting, in addition to its emphasis on geometry, can be alternatively viewed as a reaction against the pure, bright colours of the Fauves and the spontaneous colour treatment of the impressionists. Cubist art was largely influenced by the later work of Paul Cézanne and the study of primitive art and, more precisely, African religious masks, statuettes, and artefacts. Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) and Braque’s Maisons à l’Estaque (1908) are considered the first manifestations of proto-cubist painting.

Influenced by Picasso and Braque, artists such as Fernand Léger (Les Fumeurs, 1912), Juan Gris (Grapes, 1913) and Robert Delaunay (Windows, 1912) developed their own distinctive cubist styles. They introduced new ways of working with colour, geometry, and elements of abstraction (Léger, Contraste de formes, 1913). Alternative cubist perspectives were also introduced by painters such as Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Le Fauconnier, Roger de La Fresnaye, André Lhote, and sculptors such as Jacques Lipchitz and Henri Laurens. Cubism’s influence was not limited to painting and sculpture but extended to architecture, poetry, music, literature, and the applied arts.

Source: Paris, Musee Picasso. © 2016. Photo Scala, Florence

Conceptual and perceptual Cubism

Cubism gained worldwide recognition from the second decade of the 20th century onwards. As its influence spread, a large number of cubist styles emerged that differed substantially from those of Picasso and Braque. This variation mainly resides in the perceptual, either quasi-figurative (Lhote, L’Escale, 1913) or purely abstract cubist perspective that several artists brought forward (Delaunay, Fenêtres ouvertes simultanément, 1912). In addition to the emphasis on solid geometry, a number of artists replaced Picasso and Braque’s use of greys, browns, and blacks with a more vivid palette (La Fresnaye, The Conquest of the Air, 1913).

In fact, the style was never homogenous but raised controversy among its agents. This became evident in 1911, with the emergence of the so-called Puteaux Group (1911–13) of cubist artists, including Alexander Archipenko, Gleizes, Metzinger, Frank Kupka, Marcel Duchamp, and Léger, who frequented the studios of Jacques and Raymond Duchamp-Villon in the western suburbs of Paris. The group’s art can be viewed as a reaction against the conceptual approach of Picasso, Braque, and Gris, who were generally called the Montmartre cubists. A similar reaction is manifested in the works of several other artists such as Lhote and La Fresnaye who practised a perceptual and quasi-figurative style.

Although most of these artists taught Cubism in private art academies and had exhibited their compositions since 1911 at the Salon des Indépendants (Salle 41) and the Salon d’Automne, the generators and leaders of this style (Picasso, Braque, Gris, Léger) worked largely in private under the patronage of the German-Jewish art dealer Daniel Henri Kahnweiler who invested in their works for his stock. Clearly, this fact not only contributed to the popularisation of the perceptual and the geometrically abstract cubist technique in the following decades, but also reflects the over-simplified and legible repertoire of most of these artists in opposition to the constant experimentation and renovation of the artists Kahnweiler supported. Major works by Picasso, Gris, and Braque were kept in Kahnweiler’s stock, which, at the outbreak of the First World War, was confiscated as enemy property and was sold at auctions between 1920 and 1923. The stock contained more than 800 works most of which were presented to the public for the first time at auction, generally fetching low prices. This incident was considered a blatant attack against the aesthetic of Cubism.

Source: Photograph courtesy of Sotheby's

Despite the fact that it is referred to as a movement, the heterogeneity of Cubism is an oft-quoted reality. In Les Peintres Cubistes (1913), Guillaume Apollinaire observed the co-existence of four cubist tendencies, only two of which were developed in a parallel and pure way: scientific Cubism, physical Cubism, instinctive Cubism and orphic Cubism. According to Apollinaire, scientific Cubism, practised by Picasso, Braque, Metzinger, Gleizes, Laurencin, and Gris, is a pure tendency. Physical cubism, practised by Le Fauconnier, is not pure art since it confounds subject with images. The instinctive tendency derives from French Impressionism and has met significant expansion throughout Europe. It is practised, however, by artists who are not necessarily cubist representatives such as Henri Matisse, Georges Rouault, André Derain, Raoul Dufy, Jean Puy, Kees Van Dongen, Gino Severini, Umberto Boccioni, and others (ibid. 2013, 84). Finally, orphic Cubism is the second pure tendency, which is practised by artists who do not depend on virtual reality but who create a reality of their own. Representatives of this pure tendency are Picasso, Delaunay, Francis Picabia, Léger, and Marcel Duchamp. To his own disappointment, Lhote was not listed among the cubists in the book.

Lhote attempted to establish his own division among cubist artists. Commenting on the 31st Salon des Indépendants in 1920, he identified two cubist schools:

There are four nuances of cubism: two absolutely opposite currents lead, by the opposed roads of painters and sculptors, towards two goals, which are united only by their antagonism … There is plenty of talent in both camps, and talent alone will decide the final selection. I simply desire to define as precisely as I can the attitude of those whom I call, for my purposes only, cubists a priori or pure cubists, and the cubists a posteriori or emotional cubists.

(‘The Two Cubisms’, The Athenaeum, pp. 547–48)

Analytic and synthetic Cubism

Due to its complexity, Cubism became subject to several formal and stylistic categorisations and even philosophical interpretations. Its division into the two phases ‘analytic’ and ‘synthetic’ has been widely used, although it is chronologically flexible and has been questioned by scholarship as it was not literally accepted by cubist artists. The terms were introduced by Kahnweiler who used them to classify the stylistic experimentations of Picasso and Braque.

Analytic Cubism, also referred to as ‘hermetic Cubism’, is a term used to describe the early achievements of the cubist stylistic innovations and extends approximately from 1910 to 1912. It concerns the simultaneous depiction on a two-dimensional surface of several sides of a three-dimensional object-subject (Picasso, Portrait of D.-H. Kahnweiler, 1910). Although this technique may be seen as abstract it is, in reality, essentially figurative but aims to re-treat and reinterpret the conventional composition. Therefore, the depicted objects are mainly still lives that tend to become easily recognisable as they draw inspiration from everyday life (bottles, tables, musical instruments, books, newspapers, etc.), often accompanied by letters or words that describe them.

Synthetic Cubism extended from 1912 to 1914 and introduced the collage technique, the use of vivid colours and different types of materials, mainly paper (wallpaper, papiers collés, paper cut-outs, textiles, etc.), that contribute to the maintenance of the solid structure of the composition and render it legible through the creation of an architectonic illusion of space and volume. This phase exerted considerable influence over the surrealist treatment of the object.

Cubism and tradition

Although Cubism was initially viewed as a total break with traditional composition, in due course the movement’s critical reception and interpretation was transformed. The cubist artists-theoreticians Gleizes and Metzinger had published texts on Cubism and tradition in Parisian journals between 1911 (Paris-journal) and 1913 (Montjoie). Mark Antliff (1992) argues that Gleizes’ association of Cubism with the Gothic era reflects his leftist allegiances and the formulation of a Celtic nationalism as opposed to right-wing nationalism and its attachment to the Greco-Latin tradition identified with French race. In order to normalise cubist practice, Gleizes and Metzinger published Du Cubisme, establishing a theoretical framework for Cubism which stressed the movement’s connection to Realism:

To understand Cézanne is to foresee cubism. Henceforth we are justified in saying that between this school and previous manifestations there is only a difference of intensity, and that in order to assure ourselves of this we have only to study the methods of this realism, which, departing from the superficial reality of Courbet, plunges with Cézanne into profound reality, growing luminous as it forces the unknowable to retreat.

(1912, 9).

In Les Peintres Cubistes , Apollinaire also stressed the parallels between Cubism and tradition, notably by comparing the geometry of Renaissance art with non-Euclidean geometry and the ‘fourth dimension’. Although the references to the imperceptible ‘fourth dimension’ gradually vanished from writings on Cubism in the years that followed, it appears that it was a portmanteau term in the 1910s. Apollinaire’s discussion of the concept is somewhat ambiguous. Although he employed the term in his text, he noted that

the fourth dimension is the manifestation of the aspirations, the inquietudes of a large number of young artists who looked at Egyptian, Negro and Oceanic sculptures, meditated scientific works, anticipated a sublime art to which today more of an utopian expression rather than a historical interest may be attached.

(1913, 16–17)

In Cubisme et Tradition (1920, 12), Léonce Rosenberg discussed Cubism in terms of an ‘orderly’ break with tradition stressing the idealist aspects of the movement: ‘Similar to the primitives, also impelled by the synthetic spirit, the cubists, start from visual reality to reach ideal reality.’ In 1927 Rosenberg further developed his ideas. He maintained that the cubist synthetic style drew parallels from the Middle Ages. Although Renaissance art imposed analytical doctrines, 20th-century art recovered the medieval aspect of synthesis. He wrote:

This is how humanity evolves, the Picassos, Légers, Valmiers, are the Cimabues of contemporary art. Without cubism, the passage from static to dynamic, instant to permanent, concrete to abstract, neutral to radiant, flat to volume, local to universal, was impossible.

(‘Entretien avec Léonce Rosenberg’, Feuilles Volantes 6, 1927, 2)

Others connected Cubism to Picasso’s own national identity. The American novelist and cubist champion, Gertrude Stein insisted that Cubism is a southern phenomenon originating in Spain:

Cubism is part of daily life in Spain, it is in Spanish architecture … Nature and man are opposed in Spain, they agree in France and this is the difference between French cubism and Spanish cubism and it is a fundamental difference.

(1946, 293–98)

Following the pre-First World War debates over the German identity of Cubism, the German collector Wilhelm Uhde identified in Picasso et la tradition Française (1928) two distinct schools of Parisian Modernism. The first, inherent to French tradition, was analytic in style and found expression in Impressionism, Renoir, and finally Matisse. The second tendency was synthetic and owed much to the German tradition. Although it was introduced by Cézanne and Seurat, it achieved a total break with national tradition through the work of Picasso.

Cubist exhibitions

Braque’s proto-cubist paintings of Estaque were exhibited by Kahnweiler in 1908. These works literally constitute the first cubist landscapes. Apollinaire signed the text for the catalogue without reference to ‘Cubism’ since the term was established shortly afterwards. According to Kahnweiler, Vauxcelles invented the name after Matisse told him that Braque sent to the Salon d’Automne in 1908 paintings ‘avec des petits cubes’, referring to Braque’s landscapes of l’Estaque, which were rejected by the jury. Kahnweiler did not approve of the name:

From Matisse’s word ‘cube’ Vauxcelles then invented the meaningless ‘Cubism’ which he used for the first time in an article on the 1909 Salon des Indépendants, in connection with two other paintings by Braque, a still life and a landscape … the name ‘Cubism’ endured and entered colloquial language, since Picasso and Braque … cared very little whether they were called that or something else.

(1949, 5–6)

The works of the so-called Salon cubists (Archipenko, Delaunay, Duchamp, Le Fauconnier, Gleizes, Léger, Lhote, Metzinger) were first presented at the 26th Salon des Indépendants in 1910. The Salle 42 at the 27th Salon des Indépendants in 1911 hosted the first organised cubist show in the history of the movement. That same year, the Salon cubists also presented their work at the ninth Salon d’Automne with Kupka among them, while they also gave a second show at the Parisian Galerie d’Art Contemporain supported by the Société Normande de Peinture Moderne.

Cubist architecture was introduced at the decorative arts section of the 1912 Salon d’Automne with the construction of the Maison Cubiste [Cubist House]. The facade was designed by Raymond Duchamp-Villon with the interior attempting to adapt cubist painting to bourgeois life (Salon Bourgeois). The construction not only introduced cubist art to the domestic environment, but also established the foundations for the emergence of Art Deco design. The installation was also presented the following year at the Armory Show (New York, Chicago, Boston) which introduced Cubism to an American audience. It is worth noting, however, that the term ‘Cubism’ did not appear in the catalogue’s description of the work.

Works by Parisian cubists were exhibited in Germany at the beginning of the century. The third Sonderbund westdeutscher Kunstfreunde und Künstler [Separate League of West German Art Lovers and Artists] that was held in Cologne presented to the German public a significant sample of Parisian Modernism as early as 1912. The exhibition was mainly aimed at museum directors who intended to purchase modern works for museum collections. In fact, the first work by Cézanne (Le Moulin sur la Couleuvre, 1881) that entered a museum collection was acquisitioned in 1897 by Hugo von Tschudi for the Alte Nationalgalerie in Berlin.

The increasing number of exhibitions and theoretical texts on Cubism indicate by and large the expansion of the movement’s reputation and the popularisation of its aesthetic principles. Following the first Salon de la Section d’Or in 1912, the artists belonging to the named group organised two more shows after the First World War. The second Section d’Or exhibition was also held with the support of Rosenberg at his Parisian gallery in 1920. However, Cubism was grouped this time with De Stijl and Bauhaus artists, constructivists and futurists, artists promoted by the art dealer at his gallery. The show did not draw positive attention. Cubism was considered outdated and became the target of attack by dadaists. The third show, mainly a retrospective, was held at the Galerie Vavin-Raspail in 1925.

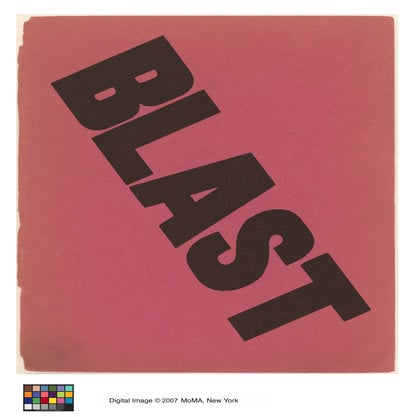

The exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art organised by Alfred Barr at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1936 is a milestone in the history of the movement. The diagram printed on the front cover of the exhibition catalogue established a genealogy for Cubism which is presented as the legitimate offspring of the formal simplification of primitive art and the heroic progenitor of abstraction. The catalogue confirmed that Cubism was by that time a historical movement, claiming the right to institutionalisation.

After Cubism

The influence of Cubism extends well beyond the first two decades of the 20th century. Although many artists and critics declared the ‘end’ of the movement at the beginning of the 1920s, Lhote remained faithful to the Cézannesque formula, maintaining that it had ‘defined painting for a century or two, and perhaps for longer still’. The artist lent a sympathetic eye to the naturalist turn of Cubism after the war, which brought the movement closer to the French tradition. He was convinced that Cubism still had a long way to go until it reached its end. Lhote declared:

to discover a definitive formula too soon would be to confuse death with stability, and not to understand that the intoxication one experiences in constructing a work of art has after all some resemblance to a departure for distant adventures.

(‘The Two Cubisms I’, The Athenaeum, 23 April 1920, 547–8)

In 1921 the Italian Gino Severini, stressed the transition from Cubism to Classicism in his book Du cubisme au classicisme: esthetique du compass et du nombre. The post-futurist artist thought that sensibility in contemporary art led to painterly deformation. He proposed instead a return to the classic canon and the union between science and art. ‘Art is humanised science’, he declared. Severini denied any classic qualities in the work of Cézanne, arguing that ‘we do not become classic through sensation, but through spirit’ (1921, 19).

Cubism was viewed by many as ‘a tragic image of a transitional era’, as J.J.P. Oud wrote in 1923. Perhaps the most systematic effort to revitalise the movement’s influence between the wars was marked by Rosenberg with his Galerie de l’Effort Moderne and the homonymous bulletin that published 40 issues between 1924 and 1927. The cubist art dealer promoted the idealist aspects of cubist painting although he did not approve of Picasso’s turn to classical form in the period 1917–25 as much as his brother Paul Rosenberg, who signed a contract with the artist. To a certain extent, his positions were in keeping with those of the cubist champion Maurice Raynal. The Bulletin de l’Effort Moderne became a meeting point for artists who sought to take the lesson of Cubism further, including essays on Neoplasticism, the mechanist aesthetic, and geometrical abstraction. It also reproduced texts by De Stijl artists and other abstractionists. Rosenberg was principally concerned with keeping alive the influence of the movement and advocated tendencies that were regarded with scepticism by the more conservative supporters of Cubism.

By 1928 Cahiers d’Art, an influential Parisian art magazine with strong attachments to Picasso, had announced the end of Cubism. Christian Zervos founded the magazine in 1926 seeking to direct and influence the course of contemporary art after Cubism. His collaborator, Tériade, confirmed in his 1928 book on Léger the ‘end of an era in the evolution of painting, the moment when results and consequences begin to appear’. In a series of articles entitled ‘Documentaire sur la jeune peinture’, the art critic named the various abstract tendencies that had Cubism as a point of departure but, to his own disappointment, misinterpreted the essential formal values of its aesthetic. Tériade literally condemned the artists who wished to develop or continue cubism. In art, he maintained, nothing is to be continued (‘Conséquences du cubisme’, Cahiers d’Art 1, 1930, 17–27).

Works

References and further reading

Antliff, M. (1992) ‘Cubism, Celtism, and the Body Politic’, Art Bulletin 74(4): 655–668.

Antliff, M. and Leighten, P.D. (2008) A Cubist Reader: Documents and Criticism, 1906–1914, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Apolllinaire, G. ( 1913 ) Les peintres cubistes , Paris : E. Figuière , https://archive.org/details/lespeintrescubis00apol.

Cooper, D. (1983) The Essential Cubism, 1907–1920: Braque, Picasso and their Friends, London: Tate Gallery.

Cottington, D. (2004) Cubism and its Histories, Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press.

Gee, M. (1981) Dealers, Critics, and Collectors of Modern Painting: Aspects of the Parisian Art Market between 1910 and 1930, New York and London: Garland.

Giroud, V. (2007) Picasso and Gertrude Stein, New York: MoMA.

Golding, J. (1959) Cubism: A History and an Analysis, 1907–1914, London: Faber & Faber.

Green, C. (1987) Cubism and its Enemies: Modern Movements and Reaction in French Art, 1916–1928, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hicken, A. (2017) Apollinaire, Cubism and Orphism, Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Kahnweiler, D.H. ( 1949 ) The Rise of Cubism , New York : Wittenborn and Schultz , https://archive.org/details/riseofcubism00kahn/page/n9.

Kolokytha, C. (2016) Formalism and Ideology in 20th Century Art: Cahiers d’Art, Magazine, Gallery and Publishing House (1926–1960), PhD thesis, Northumbria University.

Roskill, M.W. (1985) The Interpretation of Cubism, Philadelphia: Art Alliance Press.

Rubin, W.S. (1989) Picasso and Braque: Pioneering Cubism, New York: Museum of Modern Art.

Stein, G. (1946) Selected Writings of Gertrude Stein, New York, Random House, https://archive.org/details/selectedwritings030280mbp/page/n7.