Overview

Surrealism Overview By Ortolano, Scott; Marwood, Kimberley; Capkova, Helena; Wu, Chinghsin; Butler Palmer, Carolyn; Ramos, Imma; Mitchell, Ryan Robert; Ortolano, Scott; Marwood, Kimberley; Capkova, Helena; Wu, Chinghsin; Butler Palmer, Carolyn; Ramos, Imma; Ortolano, Scott; Mitchell, Ryan Robert

Overview

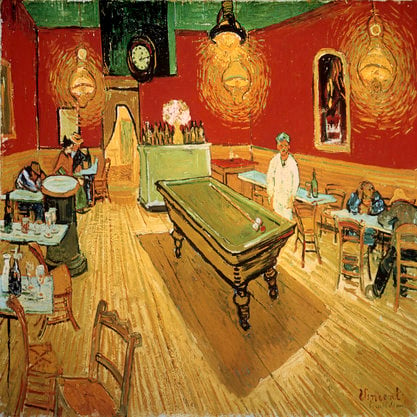

Soupault’s publication of Manifeste du Surréalism in 1924. Rising in the wake of the First World War, Surrealism revolted against a world that had become deadened by habit, cliché and scientific rationality. The movement was an offshoot of Dada, which emerged in Zurich in 1916. Dadaism and Surrealism both created work that mocked and insulted bourgeois aesthetic, moral and social norms. However, Dada held that all ideals were inherently absurd and substituted nothing for the norms it ridiculed. Surrealism instead drew upon Sigmund Freud’s belief that a primal, non-rational Id lurked beneath our rational intellect and idealized the creative potential of the subconscious

Surrealists dedicated themselves to collapsing the barrier between the dreaming and waking worlds. They developed techniques to suppress their rational intellect and tap into unconstrained consciousness. Using automatism, artists and writers worked in a trance-like state without interruption or later revision as a means of producing unfiltered art. Surrealists also emphasized collaboration and chance occurrence. This produced techniques like the exquisite corpse, in which individuals took turns drawing figures or writing lines while simultaneously obscuring preceding sections of text or the image. Furthermore, because of their interest in non-rational states of being, Surrealists idealized those who lived outside the bounds of traditional society. Breton famously said that ‘beauty will be convulsive or will not be at all’, and this revolutionary spirit helped to reenergize fields that had largely reached a state of decadence.

Source: The Philadelphia Museum of Art / Art Resource / Scala, Florence © Succession Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2016

Surrealism

Originating as a literary movement in Paris, Surrealism was initially defined in relation to its literary precursors in the early periodical Littérature (1919–24), set up by artists and writers including André Breton, Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault. In 1924, Breton formally enunciated the intentions of Surrealism in the Manifeste du surréalisme (Manifesto of Surrealism, 1924). The principle aims of the manifesto were to define Surrealism, declare its members and communicate its methods and intentions. In the same year, writers and artists including Paul Éluard, Louis Aragon and Benjamin Péret, set up the ‘Bureau of Surrealist Research’, an office space in a central Paris location where they aimed to record the forms and expressions of the subconscious mind. These findings were discussed and documented in the pseudo-scientific periodical La Révolution surréaliste (1924–29). Members of the movement during this period included prominent visual artists such as Max Ernst, André Masson, Hans Arp, Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, with others joining the movement, such as Salvador Dalí, Francis Picabia, Méret Oppenheim, Yves Tanguy and Alberto Giacometti in the mid-1920s, as Surrealism gained more attention. Other key visual artists associated with the movement include Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró, who never officially joined but exerted influence on Surrealism and adopted surrealist principles in their own work. Surrealism found international success in the 1930s, survived the Second World War and expired in the 1960s.

Surrealist ideas were influenced by the rising popularity of psychoanalysis in the 1920s and 1930s and informed by the ideas of Sigmund Freud. Freud’s theories of the unconscious underpinned Surrealism’s emphasis on the creative possibilities of chance, desire and dream. Rather than create purely objective representations, the Surrealists, as ardent disciples of Freudian psychoanalysis, favored inner experience and the unconscious. Through ‘psychic automatism’ the Surrealists created an alternative means of experiencing reality. Automatic writing, the manifestation of this process, superseded the novel as Surrealism’s chosen textual format. Automatic writing was supplemented by the development of new visual techniques in which unusual juxtapositions of objects and images were combined through methods including photomontage and collage, produced by artists like Max Ernst and Dora Maar. Ernst pioneered the ‘automatic’ processes of frottage and grattage. André Masson explored the process of automatism through drawing and paint, Man Ray pioneered experimental photographic techniques, and Dalí realised surrealist ideas through paint, installations and surreal objects. Oscar Dominguez made use of delcalcomania, where paint is applied to paper which is then folded or pressed against another sheet, the resulting image sometimes augmented by drawing. Picasso also employed surrealist themes and techniques in his practice, exploring violence, eroticism and metamorphosis during the 1930s. Aspects of Surrealism can also be traced in the paintings of Miró. After moving to Paris in 1921, Miró’s paintings, such as The Tilled Field (1923–24), became more imaginative and dream-like, leading Breton to describe him as the ‘most surrealist of us all.’

Surrealism was also underpinned by a strong political ideology. Surrealism emerged out of Dada, a movement whose nihilist, anti-art sentiments were developed as a response to the state of Europe after the First World War. Most Surrealists subscribed to a Trotskyist interpretation of Marxism and aligned themselves with Communism. Political, ideological and creative differences led to a number of splits in the group by the time of the Second Manifesto of Surrealism in 1930, with a number of members excluded from the group. Dalí was later rejected because of his supposed support of Francisco Franco’s fascist regime in Spain and Georges Bataille and Antonin Artaud also departed from the surrealist group due to ideological differences. Bataille went on to pioneer his own form of dissident Surrealism in the periodicals Documents (1929–30) and Acéphale (1936–39).

As the movement gained traction in Paris, its influence took hold in other countries, attracting artists from Belgium like René Magritte, Paul Nougé and Marcel Mariën, with a strand of the movement founded in Czechoslovakia in 1934 by poet Vítězslav Nezval, before reaching the Americas in the early 1940s when many Surrealists left occupied France during the Second World War. In Britain the movement came into prominence in the 1930s. Roland Penrose catalyzed the development of a British surrealist movement which included Henry Moore, Humphrey Jennings and Eileen Agar. Surrealism (1936), a collection of essays edited by critic Herbert Read was published in 1936 on the occasion of the ‘International Surrealist Exhibition’, which opened at the New Burlington Galleries in London in June 1936. Following David Gascoyne’s A Short Survey of Surrealism (1935), the exhibition introduced Surrealism to a British audience, affirming the existence of a British surrealist group, which had been functioning without formal unity through exhibitions and periodicals from the early 1930s. In the postwar period surrealist activity continued with major exhibitions in Paris and New York, yet was geographically dispersed and often absorbed and overshadowed by developing abstract movements such as Abstract Expressionism.

Scholarly discussions of Surrealism have increasingly departed from a focus on a canonical body of artists and writers (circulating around Breton) to a broader understanding of Surrealism, which encompasses marginal figures and the geographical expansion of Surrealism across Europe, Japan and South America. Coupled with a growing awareness of Surrealism’s relationship to politics, science, psychoanalysis and other intellectual impulses of the period, like the occult, such approaches have presented a fuller picture of Surrealism and celebrated its impact on twentieth-century thought and culture. Surrealism’s influence on queer artists and theory, for example, have now been explored in the work of artists Claude Cahun and Pierre Molinier. Women artists have also received increasing attention in the context of Surrealism. Historically, the celebration of creativity and its relationship to sexual desire within Surrealism occluded the expression of women who were positioned as muse, femme fatale, or femme enfant. Women were often not members of the official group; rather, contributed as partners or creative subjects and were largely excluded from official activities. Correlating with the rise of Feminism and the establishment of a feminist art history, Xavière Gauthier’s Surréalisme et Sexualité (1971) sparked a series of critical responses to this male dominance. A striking amount of critical attention has since been devoted to the role of sexuality and desire in surrealist art. Landmark studies, which sought to rectify the marginalization of women in surrealist practice, such as Whitney Chadwick’s Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement (1985) and the exhibition Mirror Images: Women, Surrealism and Self-Representation (1998) and its accompanying literature, have opened up new readings of the role of women in Surrealism. Female artists such as Dorothea Tanning, Dora Maar, Claude Cahun, Leonora Carrington, Leonor Fini, Remedios Varo, Meret Oppenheim, Valentine Penrose and Lee Miller are now celebrated as artists on their own terms.

The word ‘surreal’ is now commonly used as an adjective to describe the unusual or unexpected. Despite the term’s detachment from the original movement, methods and ideas generated in the context of Surrealism have endured and are recognizable in contemporary art practice. Artists, including Louise Bourgeois and swathes of YBAs, adapted methods and ideas pioneered by surrealist artists, such as the objet trouvé (found object). Surrealism’s contribution to the development of experimental cinema also endures with the work of directors like Luis Buñuel continuing to have influence today. After Breton’s death in 1966, many believed that Surrealism, as an official movement, was over. Yet, collectives which developed from the Parisian origins and identify themselves as surrealist are still active across Britain in Leeds, London and Birmingham, and in Czechoslovakia and Chicago.

Czech Surrealism

The Surrealist Group of Czechoslovakia was a group of fine artists and literary authors founded in 1934. The goals of the group were shared with the international surrealist movement lead by Andre Breton. His second manifesto, published in 1929, and his visit to Prague in 1935 were of particular importance for the Czechoslovak group that still operates today. Important members of the original group included: K.Teige, K. Biebl, Toyen, B. Brouk, J. Štyrský, V. Makovský, J. Ježek and J. Honzl. The history of the group is coloured with terminations and new beginnings usually determined by disagreements amongst the leading members. In 1938 the founder, poet Vítězslav Nezval dismissed the group in protest against the anti-Soviet ideas of the majority of its members. Some of the remaining members ignored Nezval’s action and continued their activities until 1939. Jindrich Štýrský’s death in 1942 marked the completion of the decline of the group, during which time it was deserted by many members who emigrated abroad and the remaining group included only Teige, Toyen and a newer member, the young artist and protégé of Toyen, Jindřich Heisler.

Yet the new generation of Czech surrealist artists had already formed. The group Ra edition formed in 1937 by younger generation artists such J. Istler, L. Kundera, Z. Lorenc, M. Miškovská and O. Mizera. This diverse group shared the same point of reference of the established theorist Karel Teige. Their activities, including publishing, continued during the Second World War and in 1947 Ra Group was formed and introduced in an exhibition, catalogue and an edited volume of texts. The members of Ra Group include two poets (L. Kundera, Z. Lorenc) and six artists (J. Istler, M. Koreček, B. Lacina, V. Reichmann, V. Tikal and V. Zykmund). Their approach left behind some of the key concepts of Surrealism, such as psychic automatism, and aimed instead to focus on creative processes which continue to resonate with contemporary art movements, such as informal or Abstract Expressionism. They sympathized with communist party ideals and aimed to connect with similar groups abroad as exemplified by their attendance at the International Conference of Revolutionary Surrealism in Brussels in October 1947. After the dramatic change in the Czech political landscape in 1948, which resulted in power landing in communist hands, the artists were strictly prohibited from contacting other artists abroad and the group was disbanded. However, Teige’s group was able to re-establish itself in 1950 and the wider art scene also became home to some solitary surrealist artists such as Marie Pospíšilová, Emila Medková, Karel Hynek and Vratislav Effenberger, who later replaced Karel Teige as the leading theorist of the surrealist group.

Until his death in 1951 Teige tirelessly tried to renew the surrealist activities he had started before the war, failing, however, to find a likeminded group. Eventually he contacted the Spořilov (a neighbourhood in Prague) Surrealists who, together with a few others accepted him into their fold. This group published ten volumes of the journal Zodiac Signs, and eventually, under the totalitarian government, the Spořilov Surrealists morphed into an illegal, underground movement.

Japanese Surrealism (Chôgenjitsushugi, 超現実主義)

Japanese Surrealism began as a literary movement in the mid 1920s when French surrealist theories and literary works were first translated into Japanese, and a number of Japanese poets and writers began to claim Surrealism as the primary inspiration for their writing. In 1928, several Japanese artists began to create Surrealist-style works, and in 1929, the works of three Japanese artists, Abe Kongō (1900–1968, 阿部金剛), Tōgō Seiji (1897–1978, 東郷青児), and Koga Harue (1895–1933, 古賀春江), at the Second Section art exhibition were labeled ‘surreal’ by critics, marking the beginning of Surrealism as a visual practice in Japan. By 1930, Surrealism as a visual art movement was being widely discussed and debated in Japanese art circles, including paintings and photography. While French Surrealists’ works had a great influence on Japanese Surrealist art, reflected in the dream-like scenery, fragmented and disordered bodies, and anti-rational depiction of space, many Japanese surrealist artists also included mechanical objects, scientific diagrams, and objects referring to everyday urban life. In other words, Japanese Surrealism did not merely imitate Western exemplars but broadly reflected local concerns and Japanese artists’ conflicted desires and anxieties regarding modern life, Western culture, and Japanese society.

Surrealist ideas were first introduced to Japan by poet Nishiwaki Junzaburō (1894–1982, 西脇順三郎) in 1925, a year after André Breton published Manifesto of Surrealism. However, during this initial phase, works by Breton and other Western theorists were poorly or only partially translated, and the term ‘Surrealism’ lacked a clear definition in Japan. Meanwhile, Japanese Surrealism faced harsh criticism from adherents of the Proletarian Art Movement, who criticized Surrealism as an attempt to ‘escape’ from reality, which reflected bourgeois values and failed to advance the cause of the proletariat. Within this context, various Japanese artists and critics proposed new definitions of Surrealism. Some insisted that Surrealism is firmly grounded in and inspired by reality and can help improve reality. Others, such as Takenaka Kyūshichi (1907–1962, 竹中久七), advocated a ‘Scientific Surrealism’, grounded in pure rationality, in stark contrast to the emphasis Breton placed on ‘psychic automatism’. Visual examples include several works by Koga Harue and Fukuzawa Ichirō in which scientific and mechanical objects predominate. For example in Koga’s The Sea (1929), the artist deliberately arranges mechanical objects, including an airship, submarine, and forge, emphasizing their status as symbols of modern life by placing them under the direction of a Western girl in a swimming suit.

By the mid-1930s, Breton’s writings were more or less completely translated and widely disseminated in Japan. Surrealist ideas such as automatism, unconsciousness, madness, and fantasy, were widely circulated and inspired many artists, such as Migishi Kōtarō, Okamoto Tarō, Kitawaki Noboru and Aimitsu. In 1937, the ‘Exhibition of Surrealist Works from Overseas,’ organized by Takiguchi Shūzō and Yamanaka Chirū, became a source of inspiration to both painters and photographers. Surrealism was the cornerstone of experimental photography in Japan in the 1930s, as can be seen in the works by the photography group, ‘Nagoya Photo Avant-Garde’ founded by Yamamoto Kansuke in 1937 and the related journal, ‘Yoru no Funsui’ (The Night’s Fountain), published in 1938 and 1939. Publication ceased when the Special Higher Police deemed its contents subversive. This was the time when Japan’s ruling militarists began suppressing Surrealism as antithetical to an idealized vision of the Japanese national character. It was not until the postwar period that aspects of Breton’s surrealist theory, such as automatism, recaptured Japanese artists’ attention and influenced art practices, although without inspiring a full revival of the Japanese surrealist movement.

Surrealism and dance

The Surrealists set out to destabilize the Western European paradigm that ‘knowledge’ and ‘truth’ are sight-based and rational and to challenge artistic conventions that they saw as in keeping with that line of thought. As an embodied art form, dance enabled the Surrealists to work outside these visual arts conventions to produce dynamic and multi-sensory experiences. Dance, then, played an integral role in the surrealist quest to recover truths suppressed by the development of modern Western culture over the past five hundred years; art based on linear perspective was one of the Surrealists’ most worthy opponents.

Photographer Man Ray’s short experimental film Le Retour à la raison (1923) is an early example of surrealist interest in dance. With the interjection of the word ‘dancer’ among a montage of rayographs, still photographs, manipulated stills and film clips that include the twisting torso of Kiki of Montparnasse, Man Ray equated the moving properties of film with dance. As a moving montage, the film simultaneously challenges the ‘truth value’ of the photographic medium that is yoked to the static image of Western perspective.

The intersection between film and dance also offered the Surrealists an alternative route into knowledge operating outside the Western visual arts canon. As an embodied art form, dance is also connected to the surrealist idea of ‘automatism’ or involuntary actions operating beyond the realm of conscious control such as a heartbeat or behaviors produced by intoxicants or mental illness. Louis Buñuel and Salvador Dali’s silent film, Un Chien Andalou (1928) was originally set to the beat of tango music, in an exploration of the erotic as bodily experience that cannot be entirely controlled. Likewise, Hélène Vanel’s gyrating dance-piece l’Acte manqué (1938) staged a poignant critique of the customs and constraints of polite bourgeois behavior by tapping into theories of hysteria as another manifestation of automatism.

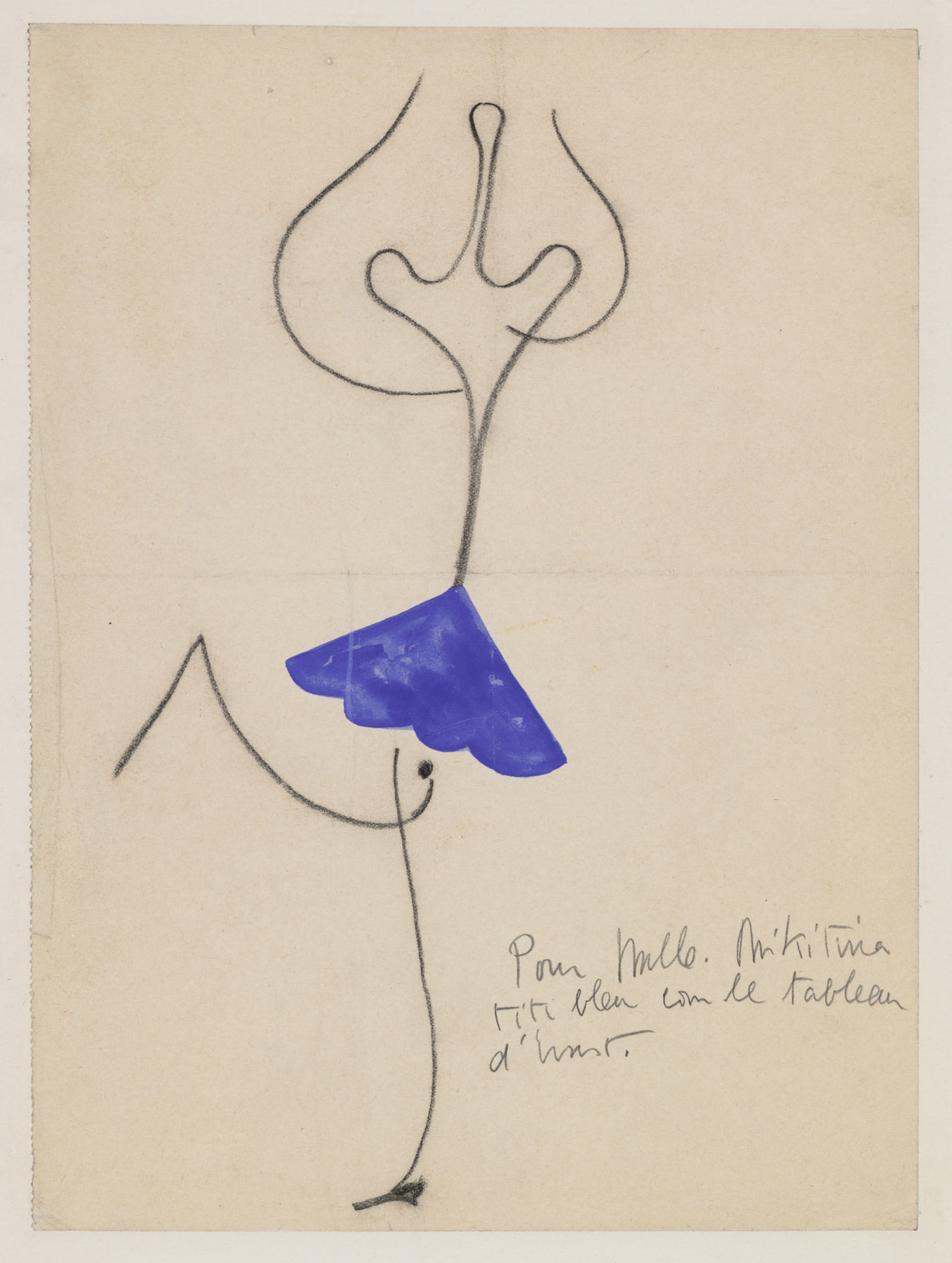

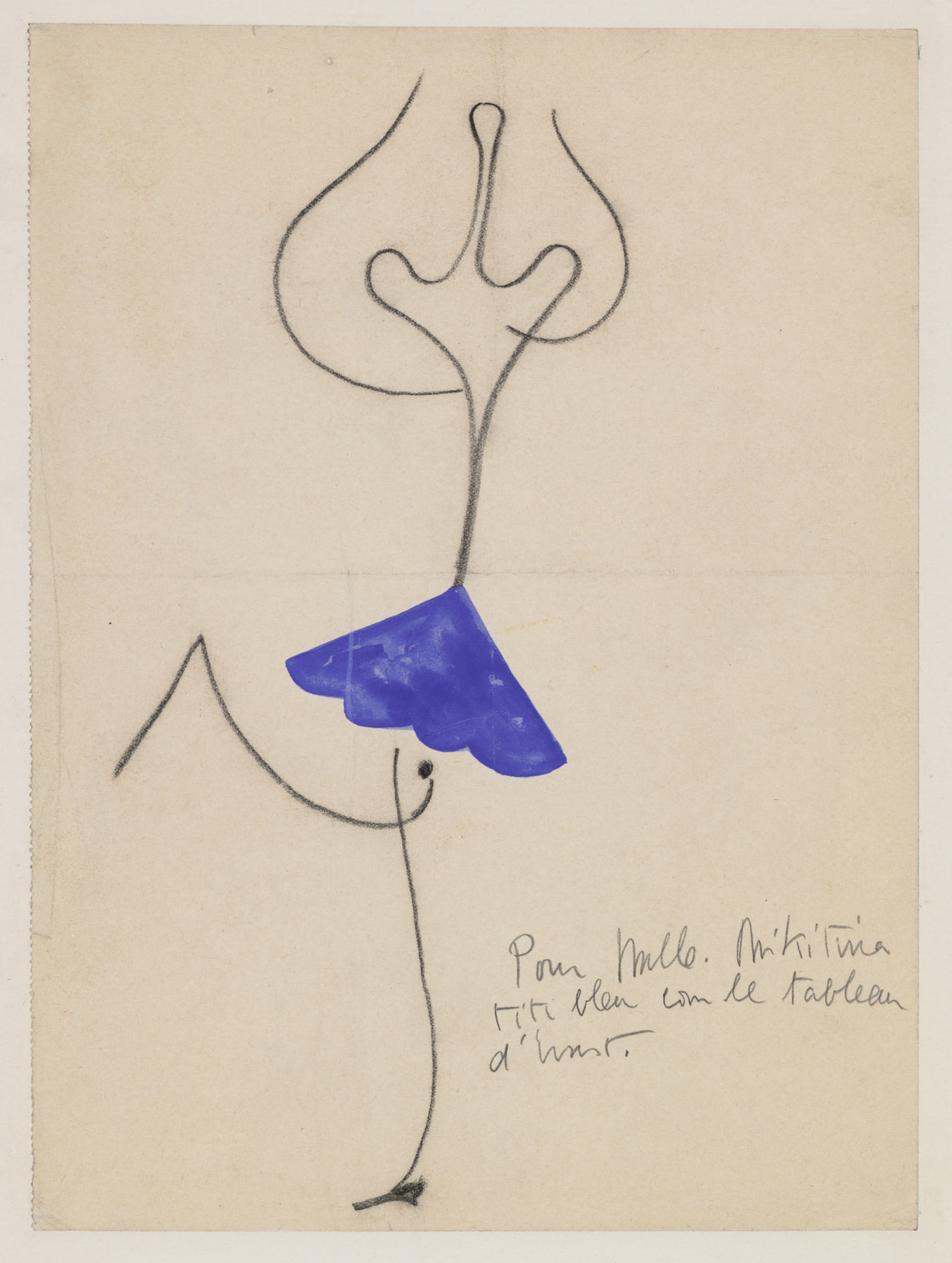

The surrealist engagement with embodiment extended to collaborations with important ballet companies and choreographers. For example, in 1926 Joan Miró and Max Ernst were responsible for the costumes and sets for Romeo and Juliet for Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. In 1945, the American-born Surrealist Dorothea Tanning created the set and costume designs for George Balanchine’s The Night Shadow.

Source: Howard D. Rothchild Collection. pf MS Thr 414.4 (105) Harvard University Library. Bequest, 1989 © Successió Miró / ADAGP, Paris and DACS London 2016

Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí worked frequently with choreographers. He was commissioned to design the sets and costumes for Leonide Massine’s Bacchanale (1939) for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo – a production in which the breast of a huge swan was used as an entrance by the dancers. In Labyrinth (1941), another choreographic work Dalí designed for Massine, the torso of a gigantic bust of a man served as way for the dancers to enter the stage. Dalí created designs for a production of Romeo and Juliet (1943), which the choreographer, Antony Tudor, declined to use. Despite this rejection, the surrealist artist continued to receive dance commissions. In 1944, for instance, he worked on Sentimental Colloquy, Café de Chinitas and Mad Tristan. In this last piece, three horses’ heads loomed over the performers. Dalí also created the sets and costumes for Ana Maria’s production of Three Cornered Hat, which Ballet Espanõl premiered at the Ziegfeld Theater in New York in 1949. Dalí was involved in dance as late as 1961, when he worked on Maurice Béjart’s Gala.

Some of the Surrealists were interested in dance beyond Western theatrical expressions. While exiled in the United States during the Second World War, Max Ernst and André Breton designed their travel itineraries through the western states with the goal of seeing Hopi and Zuni dances. Each amassed extensive collections of indigenous regalia, especially masks.

The influence of Surrealism on dance also extended to Canada, when Françoise Sullivan and Jeanne Renaud, two members of the Automatists – a multi-disciplinary group of artists in Montreal initially influenced by the French Surrealists – adapted the surrealist ideal of using spontaneity to access the subconscious to their early choreography. Sullivan wrote about the importance of spontaneity and the subconscious for choreographic experimentation in her essay ‘L’danse et l’espoir’ (‘Dance and Hope’) that was published in the Automatists’ 1948 manifesto, Refus global.

The Surrealists’ embodied practices of automatism also inspired the Action Paintings of American Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock, who blurred the boundaries between painting and dancing as documented by Hans Nemuth’s film of Pollock at work on a glass canvas.

Surrealism in Latin America

Surrealism was officially founded as a cultural movement in 1924 in Paris with group leader Andre Breton’s Manifesto of Surrealism, which expressed the movement’s aims: to show new, imaginative ways of seeing the world, and through this vision to change society. The Surrealists aimed to stimulate debate about the role of the unconscious and sexual repression in the construction of the individual. They wanted to disturb, shock and ultimately liberate society from conventions, and they did this by tapping into their own unconscious to find a new way of representing the world and also that of the viewer, to psychologically challenge and surprise them. From the 1920s onwards, the impact of the artistic movement spread internationally. The Surrealists felt that Latin America in particular perfectly articulated their own values and aims. Culturally, they understood it to be a land teeming with imagination, myth and magic that set it apart from the rational West. Local artists soon became associated with the movement, including Frida Kahlo, Rufino Tamayo (both from Mexico), Wilfredo Lam (from Cuba) and Roberto Matta (from Chile), as well as several European Surrealists who moved to the region including Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington.

Surrealist painters constructed dreamlike images, either painted in a super-real representational technique or constructed in near-abstract shapes using automatism and chance to unlock the artist’s instinctive source of creativity. The Surrealists’ experience of Latin America at first centered on Mexico, when Breton paid a visit there in 1938 and described it as ‘the surrealist country par excellence’. Art there, he felt, was intrinsically tied to magic. Surrealism was introduced to Mexico City in 1940 with the International Surrealist Exhibition at the Galeria de Arte Mexicana, organized by Breton, the Peruvian poet Cesar Moro and the Austrian artist Wolfgang Paalen. Included in the exhibition were works by Matta, Moro, Varo, Frida Kahlo and Antonio Ruiz. The latter’s Dream of Malinche (1939) reveals the influence of the Belgian Surrealist Rene Magritte with its playful juxtaposition of the corporal with the earth, and the exterior with the interior, painted with illusionistic precision.

The Mexican artist Frida Kahlo (1907–1954) is primarily known for her uncompromising and confessional self-portraits drawing on her experiences of marriage with Diego Rivera, her miscarriages and painful surgical operations. Her style combines elements of Surrealism, Symbolism and Realism, while her sources lay in pre-Columbian imagery and colonial Christian symbolism. Her Love Embrace of the Universe (1949) represents her in the guise of the Virgin Mary, holding her husband Rivera as if he were the infant Christ. Embracing the couple is the Aztec Earth Mother, Cituacoatl. ‘My surprise and joy’, Breton wrote of Kahlo, ‘was unbounded when I discovered, on my arrival in Mexico, that her work has blossomed forth, in her latest paintings, into pure surreality, despite the fact that it had been conceived without any prior knowledge whatsoever of the ideas motivating the activities of my friends and myself.’ Kahlo commented: ‘They thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn’t. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.’

Similarly, Breton singled out the paintings of the Haitian Hector Hyppolite (1894–1948), who claimed to be a voodoo priest, as quintessentially Surrealist, despite the fact that his works reflected his own reality and religion. His Ogoun Ferraille (1944) represents the voodoo warrior god Ogoun, whose attribute is the thunderbolt. Breton also acknowledged Tamayo (1899–1991) among the Surrealists. Like Kahlo, his colourful representations of figures and animals were inspired by popular art forms. During the 1940s, Tamayo began a series of paintings inspired by pre-Columbian ceramic dogs. The animals also assumed contemporary resonance as representations of anger and the horrors of the Second World War.

Like Kahlo, the exiles Varo (1908–1963) and Carrington (1917–2011) also drew on their personal experiences as marginalized female artists within a male dominated art movement. They had been associated with the Surrealists since the 1930s but it was only after they moved to Mexico in the 1940s that their oeuvre flourished, fuelled by artistic freedom and independence. Both were inspired by their studies of mythology, oriental philosophy, medieval alchemy and witchcraft. Their styles drew on surrealist subject matter combined with the meticulous technique of medieval painting. Varo’s paintings portray imaginary, androgynous, sometimes half-animal characters in confined spaces, often in the magical act of creation, as in for example Creation of the Birds (1957). Carrington was introduced to the surrealist circle in Paris by the artist Max Ernst. Her paintings are often satires of patriarchy and many represent esoteric subjects. The Temptation of Saint Anthony (1947) is influenced by a painting of the same title by Hieronymous Bosch, whose sixteenth-century proto-surrealist renderings of monstrous creatures were a major source of inspiration for both Varo and Carrington. Here Carrington adapts the story of the hermit saint to include ambiguous feminine sprite-like figures performing rituals around him. Many of her works of the 1950s represent such feminine figures as powerful priestesses overseeing rituals.

Both the Cuban artist Lam (1902–1982) and Chilean Matta (1911–2002) had traveled to Paris and become affiliated with the Surrealists during the 1930s. Lam subsequently returned to Havana where he increasingly drew on his own Afro-Cuban heritage in his work, including allusions to Santería (the popular Cuban religion fusing elements of Christianity with Yoruba African belief), which he combined with a unique stylistic synthesis of Surrealism and Cubism. His most celebrated painting, The Jungle (1943), swarms with masked hybrid creatures, half-animal, half-human. They emerge from a tropical mass of vegetation, alluding to a sugar plantation deliberately represented as a symbol of servitude, reflecting Lam’s own concerns about the exploitation of the black Cuban population. Matta experimented with surrealist automatism techniques involving thin layers of paint which he would wipe and sponge to reveal underlying forms. Such methods would result in paintings he referred to as ‘inscapes’ (representations of the artist’s psyche as interior landscapes) which he worked on during the late 1930s. In works such as Psychological Morphology (1938) he invented shapes from the unconscious. These almost abstract forms seem to be biomorphic, in the process of metamorphosing or becoming. They are archetypes of universal human experience alluding to life, death, sex and nature.

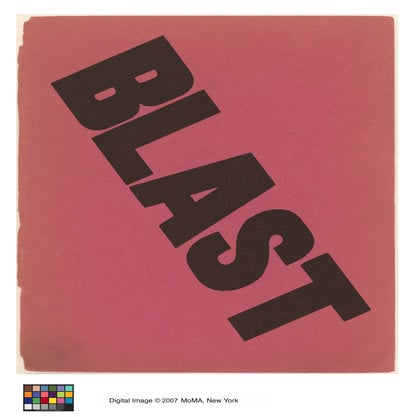

Surrealism in literature

Surrealists innovated techniques to tap the unfiltered power of the subconscious and reinvigorate the written word. Using ‘automatic writing’, Surrealists worked in a trance-like state without interruption or later revision as a means of producing work that had not been deadened by their rational intellect. Their interest in collaboration and chance occurrence produced techniques like the exquisite corpse, in which individuals took turns drawing figures or writing lines while simultaneously obscuring preceding sections of the text or image. Works created through such collaborative strategies often merged sketches, photographs, cut ups, poetry, and prose to create a collaborative collage that transcended established aesthetic categorizations. This genre blurring was itself a testament to the Surrealists’ determination to eradicate old aesthetic molds.

André Breton and Philippe Soupault’s The Magnetic Fields (1920) was the first major surrealist work and used automatic writing to create an entirely new type of poetry enlivened by the power of the unconscious. The work’s often disjointed blend of poetry and prose moved freely without regard to conventions of form or subject. While the book did not receive wide acclaim, it served as a the catalyst for further experimentation and helped to separate Surrealism from Dada, as it sought not simply to tear down established works but create a new, more potent art.

Surrealist novels used the movement’s principles to undermine and recreate the form itself. André Breton’s novel Nadja (1928) was at once a romance novel, philosophical treatise, memoir, and photographic storyboard. The work praises chance and impulse as a way of discovering meaning in a world deadened by routine and finds in a young woman named Nadja an irresistible embodiment of surrender to non-rationality and the chaotic pulls of the universe. Similarly, Louis Aragon’s Paris Peasant (1926), Philippe Soupault’s The Last Nights of Paris (1929), and the novels of René Crevel explore the cityscapes of Paris and other urban spaces – Crevel’s Babylon (1927), for example, explores Marseilles. Like Nadja, these novels display a fascination with certain locales’ ability to overwhelm the senses and produce moments of profound psychological and aesthetic intensity, what the Surrealists called ‘daily magic’. However, they also critique the crass materialism and superficiality of France and their moments of transcendence are but brief breaks in a storm of ideological and spiritual malaise. The autobiographical nature of these texts is typical of surrealist fiction, which blurs the line between fiction and non-fiction. However, such works were not limited to the urban experiences of men in France. For example, Leonora Carrington’s Down Below (1944) chronicles her institutionalization in Spain during the Second World War and guides the reader through the depths of the sanitarium and her madness. Regardless of differences in form or content, surrealist prose is distinguished by its ability to successfully collapse the boundaries between fact and fiction and consciousness and unconsciousness to provide glimpses of a reality that lies beneath and beyond our rational intellect.

Surrealist poetry moved away from regulated conventions in both form and intention, creating free-form expressions in which language was not packaged into clearly defined relationships, but became unstable and able to simultaneously invoke multiple significations. Paul Éluard, one of the leading surrealist poets, insisted on a new language that could create new modes of perception and liberate the mind. Such liberation would take a myriad of forms. Robert Desnos, who published a number of poetic collections throughout the 1920s and 1930s before dying in a concentration camp in 1945, was especially adept at using automatic writing and frequently worked under hypnosis to further free his mind from the bounds of constrained consciousness. The results were often playful and unsettling, a typical combination in the genre, but one that Desnos was especially adept at creating. When writing Rrose Sélavy (1922), Desnos entered a trance and tapped into the spiritual consciousness of Rrose Sélavy, a fictional double of Marcel Duchamp. The work includes hundreds of aphorisms that freely combine subjects, objects, and puns to offer nonsensical ‘wisdom’ that paradoxically embraces and satirizes the tradition of wisdom literature by positing ‘advice’ that exists outside of rational logic or practical application. The surrealist assault on the status quo was not limited to aesthetics and ideology, but also the political institutions that structured them. For example, Benjamin PÉRET’s poetry rejected the premise that the world must be understood. This allowed him to incorporate bizarre references, themes, and symbols, which he then used to defamiliarize symbols, experiences, and beliefs that readers would have known in a conventional sense. The goal of his work was to shock readers and undermine institutions that falsely regulated life, including the government, the army and the church. In this way, the aesthetic and existential impulses of Surrealism were inherently political, a fact that would lead many Surrealists to embrace and champion political causes during the 1940s and 1950s.

Surrealist poets’ exploration of sexual and gender norms offer a model for how the movement successfully challenged and overturned false and existentially repressive social constructions. Gisèle Prassinos, who was fourteen when she was ‘discovered’ by Breton, produced vignettes that were a blend of poetry and prose and invoked the pre-logical insights of the ‘child-woman’, who in the surrealist tradition operated outside of rational ‘adult’ discourses. Joyce Mansour’s Screams (1953), her first collection of poetry, uses Egyptian mythology to overturn purified visions of reproduction and motherhood as well patriarchal constructions of death, sex, and the female body, which objectified women and trapped them in a passive and ideologically impotent position. She continued this exploration in her later work, especially Torn Apart (1955), in which she used surrealist principles to give women agency and validate them as sexual, intellectual, and physical beings. Even works that were not feminist in a traditional sense nonetheless attempted to reimagine how men and women perceived and interacted with one another. For example, Breton’s well-known poem ‘Free Union’ (1931) envisions romantic passion free from the constraints of marriage. This theme of challenging accepted conventions, both aesthetic and social, can be seen as the unifying thread of surrealist poetry, which uses the aforementioned focus on creating a ‘new language’ to innovate, radically new understandings of art and life.

Although Surrealism’s time as a coherent school was brief, it has continued to inspire literary movements. The Beats, the New York School of Poets, and a host of other writers and movements have used the principles of Surrealism to push the boundaries of their world and, in the process, continued the transcendent vision of the movement’s founders.

Surrealism in film

Speaking of an authentic surrealist cinema is a difficult task since, outside of the first two films by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog, 1928) and L’Age d’Or (The Golden Age, 1930), there are no other films that undisputedly belong to what could be strictly called an official surrealist film canon. There is also the obverse problem where the term ‘surreal’ has entered common parlance as a synonym for the bizarre, strange, or phantasmagoric, with the label ‘surrealist’ being applied as an adjective to any film with a lurid visual style despite lacking any aesthetic or political properties that would qualify the film as a proper surrealist film. Filmmakers like, for example, Federico Fellini, Peter Greenaway, Terry Gilliam, David Lynch and Guy Maddin, have all been labeled as being ‘surrealist’ when they should be seen as being inspired by Surrealism rather than being surrealist proper. Since the radical artistic and political practices of the original surrealist movement defy any reduction to a formulaic genre or visual style, it is more productive to discuss Surrealism and cinema or the influence of Surrealism in film rather than a distinct surrealist style, genre or cinema.

The Surrealists were fascinated with the potential of cinema not only as a ‘screen’ on to which both desire and the imagination could be projected, but for its ability to reveal those elusive moments of what the Surrealists called the ‘marvelous’, or those extraordinary and wondrous contradictions that unexpectedly erupt out of everyday life. To this end, the group celebrated what surrealist film critic Ado Kyrou called the ‘involuntary surrealism’ of B-movies and the detritus of popular culture: the stage magician fantasies of Georges Méliès, the anarchic slapstick of Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, the restless pulp imagination of Louis Feuillade’s serials. Beyond this appreciation of popular culture and cinema, the surrealist group were also interested in exploring the potential of cinema through sketches for film scenarios, film criticism or film appreciation, and the production of unfilmable screenplays that gave the imagination free reign. Among these efforts, however, the original surrealist group only produced two completed films that could be considered intentional examples of Surrealism in film: Un Chien Andalou and L’Age d’Or.

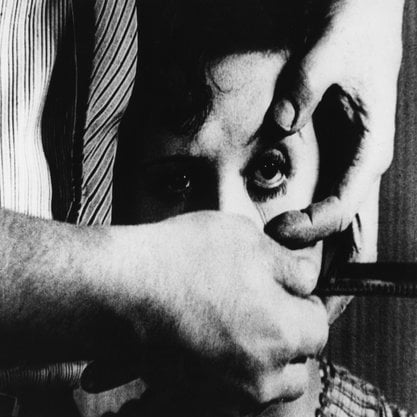

Source: © Bunuel-Dali / The Kobal Collection

The opening scene of Un Chien Andalou, the first film by director Luis Buñuel and screenwriter Salvador Dalí, begins with a close-up of a man slashing open a woman’s eyeball with a straight razor. It is one of the most famous in cinema history and it perfectly exemplifies the surrealist aspiration to have the viewer see the world with a new savage eye unconditioned by a society that represses individual desire and imagination. For the Surrealists, this type of oneiric-ocular intervention in cinema was best achieved by creating shocking images or depicting uncanny and absurd situations that would work on the viewer’s unconscious desires and obsessions. For this reason, Buñuel raged against those viewers and critics who treated Un Chien Andalou as a mere aesthetic experience and not as the ‘desperate, passionate call to murder’ (Buñuel, 1929, 34) that he intended for his film.

The surrealist group intentionally cultivated scandal, and the hostile reception and subsequent banning of Buñuel and Dalí’s second film L’Age d’Or was more in keeping with the surrealist goals for cinema. With its scenes of a woman fellating the toes of the statue or the final scene of human scalps affixed to the top of a crucifix, the film was undoubtedly created to offend the values system of both the Catholic Church and bourgeois society. Looking back on his first two films, Buñuel claimed that ‘the real purpose of Surrealism was not to create a new literary, artistic or even philosophical movement, but to explode the social order, to transform life itself” (Buñuel, 1985, 107). For this reason, any discussion of the surrealist movement must take into account the politics of Surrealism, its emphasis on desire and the imagination, and the purposes to which shock or the uncanny is mobilized.

Outside of Un Chien Andalou and L’Age d’Or, there are no other films that unquestionably belong to the so-called surrealist film canon. Even films made by artists connected to the original surrealist group were often disqualified by the group for not being properly aligned with Surrealism’s artistic or political practices. Pre-dating Un Chien Andalou by one year, Germaine Dulac and Antonin Artaud’s collaboration on the film La Coquille et le Clergyman (The Seashell and the Clergyman, 1928) is one such film with obvious Surrealist connections but was quickly disqualified as not being an official surrealist text. Scenario writer Artaud would distance himself from Dulac’s film and would arrive at the film’s premiere with Andre Breton, Robert Desnos and Georges Sadoul to heckle the film for choosing to film as the representation of a dream, of someone else’s desire, rather than a film that attempts to use cinema to induce a dream-like state in its viewers. Subsequent critics like Linda Williams (1981) and Michael Richardson (2006) would also question the validity of including The Seashell and the Clergyman as part of any so-called surrealist film canon.

Due to a loss of patronage, sectarian fracturing of the movement, and a changing and hostile political climate in Europe, the activity of the surrealist group in Paris dramatically decreased before any other films were completed. Although he would continue to make challenging films influenced by his involvement with Surrealism, Luis Buñuel, for example, left the official movement in 1932 seeing it as incompatible with his communist politics. While Surrealist painting and poetry was widely practiced outside of Europe in the 1930s, it would not be until well after the Second World War that surrealist practices would find their way into cinemas over the world.

Perhaps owing to a surrealist group active in Prague since the 1930s, Czechoslovakian cinema around the thawing of Prague Spring produced some of the most interesting films incorporating surrealist influences. Věra Chytilová’s anarchic feminist comedy Sedmikrásky (Daisies, 1966), and the Jaromil Jireš’ Valerie a týden divů (Valerie and Her Week of Wonders, 1970) are two strong examples from Czech cinema. One of the best-known Czech filmmakers, the animator Jan Švankmajer, is explicit about his commitment to the ideals of Czech Surrealism. Uninterested in the mere aesthetic appropriation of Surrealism, Švankmajer’s project for film is fully aligned with the surrealist ambition of reconciling the viewer’s repressed unconscious and their reality. Švankmajer’s uncanny animated films are preoccupied with the inner life and malevolent ontology of everyday objects, and he is best known for his ‘realized dream’ anti-fairy-tale adaptation of Lewis Carroll, Něco z Alenky (Alice, 1988) and his films Lekce Faust (Faust, 1994), Spiklenci slasti (Conspirators of Pleasure, 1996) and Otesánek (Little Otik, 2000). American animators, the Brothers Quay, were heavily influenced by Švankmajer and the early animated films of Polish Surrealists Walerian Borowczyk and Jan Lenica. Their animated adaptation of a Bruno Schulz short story, Street of Crocodiles (1986), was cited by Terry Gilliam as one of the greatest animated films of all time.

Moving image material

Man Ray’s le Retour à la raison (1923) is available for viewing at: http://www.ubu.com/film/ray.html

Louis Buñuel and Salvador Dali’s Un Chien Andalou (1928) is available for viewing at: http://archive.org/details/UnChienAndalou_313

List of works

Further reading

Aberth, S. (2004). Leonora Carrington – Surrealism, Alchemy and Art. Aldershot: Lund Humphries.

Ades, D. (1974). Dada and Surrealism. London: Thames and Hudson.

Ades, D. (1978). Dada and Surrealism Reviewed. London: Arts Council of Great Britain.

Ades, D., and Eder, R. (2012). Surrealism in Latin America: vivisimo muerto. London: Tate Publishing.

Angliviel de la Beaumelle, A. (1991). André Breton: La beauté convulsive. Paris: Éditions du Centre Pompidou.

Artaud, A. (1938/1958). The Theater and Its Double (M. C. Richards, Trans.). New York: Grove Press.

Ashton, D. (1993). Surrealism and Latin America. In W. Rasmussen, Latin American Artists of the Twentieth Century. New York: The Museum of Modern Art.

Balakian, A. (1947). Literary Origins of Surrealism: A New Mysticism in French Poetry. New York: King’s Crown Press.

Barnitz, J. (2000). Twentieth-century Art of Latin America. Austin: University of Texas.

Bate, D. (2004). Photography and Surrealism. London: I. B. Tauris.

Benson, T., and Forgács, E. (2002). Between Two Worlds: A Sourcebook of Central European Avant-Gardes, 1910–1930. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Bijutsukan, N. (1990). Nihon no shūrurearisumu: 1925–1945. Nagoya: Nagoyashi Bijutsukan.

Breton, A. (1920). The Automatic Message: The Magnetic Fields and The Immaculate Conception. London: Atlas Press.

Breton, A. (1928). Le surrealisme et la peinture. Paris: Gallimard.

Breton, A. (1930). The Automatic Message: The Magnetic Fields and The Immaculate Conception. London: Atlas Press.

Breton, A. (1931). Free Union. In T. M. Caws, Mad Love. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Breton, A. (1997). The Automatic Message. In The Automatic Message: The Magnetic Fields and The Immaculate Conception (D. Gascoyne, Trans.). London: Atlas Press.

Breton, A. (2010). Manifestoes of Surrealism. University of Michigan Press.

Breton, A., and Soupault, P. (1924). Manifeste du Surréalism. Paris.

Buñuel, L. (1929). Un Chien Andalou. La Révolution Surréaliste (12): 34–37. (full French language version available): http://melusine.univ-paris3.fr/Revolution_surrealiste/Revol_surr_12.htm

Buñuel, L. (1983). My Last Sigh: The Autobiography of Luis Buñuel. New York: Knopf.

Bydžovská, L. S. (1996). Český surrealismus 1929–1953. Prague: Argo and City Gallery of Prague.

Carruthers, V. (2013). Excessive Bodies, Shifting Subjects and Voice in the Poetry of Joyce Mansour. Dada/Surrealism, 19(1).

Carter, C. (2012). Salvador Dali: Design for the Three-Cornered Hat Ballet. Milwaukee: Marquette University epublications.

Caws, M. R. (1991). Surrealism and Women. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chadwick, W. (1985). Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement. London: Thames and Hudson.

Clark, J. (2013). Surrealism in Japan. In J. Clark, Modernities of Japanese Art. Leiden-Boston: Brill, 174–182.

Clark, J. (2013). Dilemmas of Selfhood: Public and Private Discourses of Japanese Surrealism in the 1930s. In J. Clark, Modernities of Japanese Art. Leiden-Boston: Brill, 183–192.

Crevel, R. (1925). My Body and I. Brooklyn: Archipelago Books.

Crevel, R. (1927). Babylon. Los Angeles: Sun and Moon Press.

Dalí, S. (2001). The Stinking Ass. In M. Caws (Ed.), Surrealist Painters and Poets: an Anthology (J. Bronowski, Trans.). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Desnos, R. (2004). The Voice of Robert Desnos: Selected Poems. Riverdale-on-Hudson, NY: Sheep Meadow Press.

Duncan, M. (2005). High Drama: Eugene Berman and the Legacy of the Melancholic Sublime. New York: Hudson Hills Press.

Fienup-Riordan, A. (1996). The Living Tradition of Yup’ik Masks: Agayuliyararput: Our Way of Making Prayer. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Fijalkowski, K. W. (2013). Surrealism and Photography in Czechoslovakia; On the Needles of Days. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Freud, S. (1965). The Interpretation of Dreams (J. Strachey, Ed.). New York: Avon.

Garafola, L. (2005). Legacies of Twenieth-Century Dance. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan Press.

Gavronsky, S. (2008). Joyce Mansour: Essential Poems and Writings. Boston: Black Widow Press.

Hammond, P. (Ed.) (2000). The Shadow and its Shadow: Surrealist Writings on the Cinema. San Francisco, City Lights Books.

Herrera, H. (1998). Frida: a Biography of Frida Kahlo. London: Bloomsbury.

Kaplan, J. (1988). Unexpected Journeys: The Art and Life of Remedios Varo. New York: Abbeville.

Kochhar-Lindgren, K. D. (2009). The Exquisite Corpse: Chance and Collaboration in Surrealism’s Parlor Game. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Kuenzli, R. (1996) Dada and Surrealist Film. Cambridge, MIT Press.

LaCoss, D. (2005). Hysterical Freedom: Surrealist Dance and Hélène Vanel’s Faulty Functions. Women & Performance: a Journal of Feminist Theory, 37–62.

Lewis, H. (1990). Dada Turns Red: The Politics of Surrealism. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Lindgren, A. (2003). From Automatism to Modern Dance. Toronto: Dance Collection Danse Press.

Mansour, J. (1953). Screams (S. Gavronsky, Trans.). Sausalito, CA: Post-Apollo Press.

Mansour, J. (1955). Torn apart = Déchirures. Fayetteville, N.Y: Bitter Oleander Press.

Matheson, N. (2006). The Sources of Surrealism: Art in Context. Aldershot: Lund Humphries.

Matta, R. (1975). A Totemic World: Paintings, Drawings, Sculpture. S.I.: Andrew Crispo Gallery.

Matthews, J. (1966). Surrealism and the Novel. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Matthews, J. (1976). Toward the Poetics of Surrealism. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press.

Maurer, E. (1988). Dada and Surrealism. In W. S. Rubin, ‘Primitivism’ in 20th Century Art: Affinity of the Tribal and the Modern (pp. 535–593). New York: Museum of Modern Art.

Morise, M. (2006). The Enchanted Eyes. In N. Matheson (Ed.), The Source of Surrealism: Art in Context. Burlington: Lund Humphries.

Mundy, J. (2001). Surrealism: Desire Unbound. London: Tate Gallery.

Munro, M. (2012). Communicating Vessels: The Surrealist Movement in Japan, 1923–1970. The Enzo Press.

Owen, J. (2013). Avant-Garde to New Wave: Czechoslovak Cinema, Surrealism and the Sixties. Oxford & New York: Berghahn Books.

Oxford University Press (n.d.). Art Terms. Retrieved November 3, 2015 from : http://www.moma.org/collection/details.php?theme_id=10203

Péret, B. (1981). From the Hidden Storehouse: Selected Poems. Oberlin, Ohio: Oberlin College.

Riese, H. (1988). Surrealism and the Book. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sas, M. (2002). Fault Lines: Cultural Memory and Japanese Surrealism. Stanford University Press.

Short, R. (2003) The Age of Gold: Surrealist Cinema. London: Creation.

Soupault, P. (1929). The Last Nights of Paris. Cambridge: Exact Change.

Spies, W. (1991). Max Ernst: Collages: The Invention of the Surrealist Universe. London: Thames & Hudson.

Toman, J. W. (2012). Jindrich Heisler; Surrealism under Pressure, 1938–1953. Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago.

Williams, L. (1981). Figures of Desire: A Theory and Analysis of Surrealist Film. Urbana, University of Illinois Press.