Overview

Montage By Sperling, Joshua; Barndt, Kerstin; Kriebel, Sabine; Sperling, Joshua; Barndt, Kerstin; Kriebel, Sabine

Overview

As an aesthetic principle, montage, defined as the assemblage of disparate elements into a composite whole often by way of juxtaposition, is most often associated with the Soviet cinema of the 1920s, and with the theorist and filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein in particular. This article reviews the ideas and work of Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov, the contemporaneous development of photomontage in visual design, and the connections between these movements and those in modernist painting and literature. With the advent of sound cinema and the suppression of experimental aesthetics in the 1930s’ Soviet Union, the practice of montage waned but was revived by political filmmakers in the 1960s and 1970s.

Montage in Cinema

Montage derives from the French verb monter, which translates as ‘‘to assemble.’’ With the advent of film technology, montage became the term in French to denote the process of film editing. In aesthetics, montage has a more conceptual meaning. In the context of film, it refers to the technique of combining disparate images or elements to form a composite work. Montage is related to the practice of collage; however, it differs from collage most fundamentally in the greater emphasis it places on juxtaposition—a technique often used to make a rhetorical point.

The theory of montage blossomed during the 1920s when it became a charged aesthetic concept for the Soviet avant-garde. In this historical context, the term is most strongly associated with Russian filmmaker and film-theorist Sergei Eisenstein. In his famous essay ‘‘Montage of Cine-Attractions’’ (1925) and later writings, Eisenstein developed a theory of montage—in effect, a theory of film—where discrete units (raw footage) lacked specific meaning in themselves, but only acquired meaning in their controlled recombination with other units. ‘‘The essence of cinema,’’ Eisenstein wrote, ‘‘does not lie in the images, but in the relation between the images!’’ (Aumont 1987: 146). The filmmaker’s job was thus to assemble individual cinematic shots into a composite whole, which he compared to a machine or an organism made up of cells. Throughout his career Eisenstein enumerated several methods of montage—from metrical montage, based on the length of shots, to intellectual montage based on the juxtaposition of visual symbols—but routinely called for synthesis through collision and conflict rather than linkage. In this way, the principle of montage was reasoned to reflect a Marxist understanding of history as the dialectical synthesis of opposing forces.

Eisenstein’s most famous film, Bronenosets Po’tyomkin [The Battleship Potemkin] (1925), is emblematic of his montage theory. Based on the Potemkin mutiny of 1905, and commissioned twenty years later as a pro-revolutionary testament, the film contains many canonical examples of montage-based editing, including the apparent awakening of a lion statue, and the Odessa steps sequence that distends time across several perspectives.

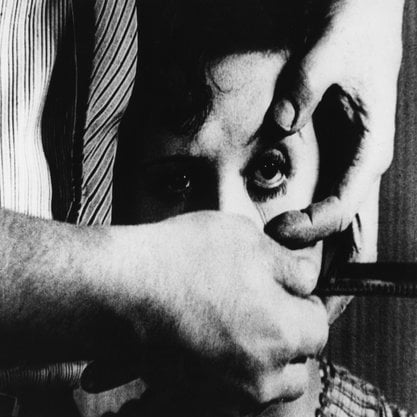

Although Eisenstein was the most vocal and advanced theorist of montage, the fundamental principle permeated Soviet cinema and arts of the 1920s. In his film workshops, Lev Kuleshov demonstrated the viewer’s psychological tendency to project causality onto a sequence of unrelated shots. Dziga Vertov, one of the first documentary filmmakers, spoke of montage as ‘‘the organisation of the seen world,’’ applying the principle not only to editing, but also to decisions made while filming, and to everyday perceptual observation. Vertov’s most famous film, Chelovek s kinoapparatom [Man with a Movie Camera] (1929), used superimposition and highly rhythmic quick-cutting to simultaneously construct a representation of urban space and represent the process of that construction. In a famous sequence, Vertov alternates between an editor splicing film and the footage being spliced.

Contemporaneous with these developments in the cinema, a genre known as photomontage, based on the cropping and rearrangement of still photographs, emerged in both Moscow and Berlin. In the Soviet Union, visual artists such as El Lissitsky and Alexander Rodchenko employed principles of dynamic juxtaposition, overlay, and re-composition in their poster and book designs. In Germany, the Dada and Bauhaus movements influenced a generation of graphic artists, including Kurt Schwitters, Jan Tschichold, and John Heartfield, who pioneered the use of photomontage in everyday visual communication. Heartfield’s photomontages, in particular, stand out for their political and rhetorical ingenuity. For example, in ‘‘The Meaning of Hitler’s Greeting,’’ a magazine cover from 1932, Heartfield places a shrunken photograph of Hitler’s salute beside a larger man in a suit holding out money, thus using montage to deliver a trenchant political point.

The principle of montage, while achieving the zenith of its expression in 1920s film and photography, developed from artistic currents that arose at the start of the century. Between 1907 and 1914, Picasso and Braque’s cubist canvasses shattered the system of fixed, singular perspective that had dominated Western art since the Renaissance. In its wake, they developed a pictorial structure predicated on the recombination of fragments into a dynamic amalgam of perspectives.

Meanwhile, the American filmmaker D.W. Griffith developed formal structures for film narrative based on dramatic cross cutting, counterpoint, and juxtaposition. His film Intolerance, first screened in the Soviet Union in 1919 and often credited as an important precursor to Soviet montage, combines four separate histories into a narrative composite.

Recent scholarship has explored the possible interrelation between montage in the cinema and the literary modernism of James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, T.S. Eliot, John Dos Passos, and others. The ‘‘Wandering Rocks’’ sequence of Ulysses, the last section of To The Lighthouse, and Eliot’s The Wasteland have all been read in relation to the practice of film editing. While some scholars have questioned these trans-disciplinary readings, the influence of montage on Dos Passos is inarguable. A translator of the Cubist poet Blaise Cendrars and an ardent admirer of Eisenstein, Dos Passos employed montage techniques borrowed from the cinema to create a panorama of American society in his U.S.A. trilogy.

After a period of florescence in the 1920s, the montage aesthetic waned in the 1930s. An increasingly repressive Soviet bureaucracy and the rise of fascism in Germany ended artistic experimentation in both countries. Contemporaneous developments in sound technology in the cinema made narrative continuity—or the perceived unity of time and space—more salient and seamless. (In response to these developments, Eisenstein extended his theories to what he called ‘‘vertical montage,’’ where the image and sound tracks operated in counterpoint rather than reinforcing one another.)

After World War II, the film-critic André Bazin developed a theory of film realism that valued the innate plenitude of raw footage over the artful manipulation of that footage. While Bazin’s long-take, deep-focus aesthetic is often understood in direct opposition to Eisenstein’s theory of montage, many of the works praised by Bazin—notably Roberto Rossellini’s Paisà [Paisan] (1946) and Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941)—make use of the montage principle in their multi-perspectival narrative structures as well as their framed compositions—if not in local editing patterns. A still from Citizen Kane, for example, reveals montage within the shot, where two separate planes of action exist in juxtaposition.

In the late 1960s, with the rise of a politicized cinema, many critics and filmmakers rediscovered the montage principle of 1920s Soviet film culture. Jean-Luc Godard, Chris Marker, as well as Latin American filmmakers Fernando Solanas, Octavio Getino, Santiago Alvarez, and Tomás Gutiérrez Alea all employed a modernist mode heavily influenced by a Soviet understanding of montage.

After the mid-1970s, however, cinematic montage waned again. Freed from its theoretical, historical and political roots, ‘‘montage’’ now most often denotes any film sequence whose editing follows an associative, rather than narrative, logic—as in many commercials or music videos.

Montage in Literature

As a literary device practiced in avant-garde movements such as Cubism, Futurism, Dadaism, and Surrealism, montage refers to the conjoining of heterogeneous discourses in a given text. Within the frame of the literary artwork, montage provokes unmediated clashes between genres and styles, often featuring non-narrative fragments from various sources such as newspaper clippings, slogans (whether commercial, political, or religious), or popular songs. Literary montage, moreover, favors disembodied discourses linked to the impact of modernity: the languages on which it draws are those of bureaucratization, commercialization, and serialization, among others. Contrasted with more character driven narrative strands, these discursive montage elements question the agency of the modern subject. Montage literature tends to playfully dissect language itself, breaking down traditional syntax and semantics in the process. It favors ambiguity, irony, and paradox over narrative unity or totality.

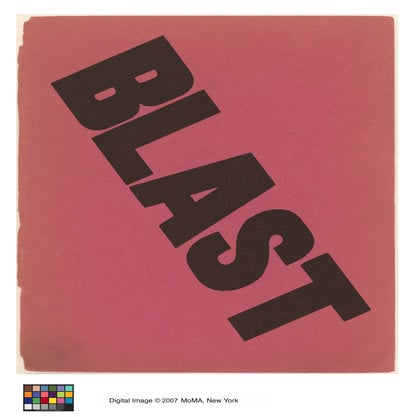

While montage theories in silent cinema drew inspiration from literature, modernist literary montage derives from the visual montages of Futurism and Dadaism. From these artistic movements, montage literature adopts formal liberties such as syntactic contractions and breaks, or visualizations through an emphasis on typography and the exhibition of words as images and sound. Furthermore, it stresses intermediality by experimenting with discourses of modern communication technologies: newspaper, radio, film, agit-prop, and advertisement. Montage literature is decisively multilingual, orchestrating literary and vernacular voices and fostering clashes among sociolects, dialects, citations from popular culture, and the playful appropriation of non-native languages.

The historical trajectory of such literary experiments encompasses modern poetry, including T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land with its citations and multilingual insertions, Gertrude Stein’s experimental prose, the deliberate contractions and visual form of futurist poetry by Filippo Marinetti, and dadaist collage and sound poetry.

Another group of avant-garde word artists indebted to montage favored the cut-up technique first promulgated by Tristan Tzara in 1920. In ‘‘How to Make a Dadaist Poem’’ Tzara describes the transformation of a newspaper article into a poem as guided by chance and the unconscious. Other Dadaists explored this technique, including collage artist Hans Arp. Brion Gysin revived cut-up poetry in the 1950s and inspired Beat poet William S. Burroughs to pursue this method in his own writings. Since 2005, Nobel laureate Herta Müller has created collage poems out of cut-up words from various print media. Like earlier literary montages, her work explores the space between image and text.

Montage is also a central device in the modernist city novel’s attempt to capture the multi-layered life-worlds of the 20th-century metropolis in Europe and the USA. The cities in Dos Passos’s Manhattan Transfer (1925), Louis Aragon’s Le Paysan de Paris (1926), and Alfred Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929) emerge out of a cacophony of focalized voices and anonymous, disembodied discourses. These authors borrow from contemporary news media to break up their storylines with unrelated documents of public life. While fiction and documentation seem to clash, these authors also tend to draw the specific temporality of the document into their at times dreamlike and mythologizing narratives. The city novels’ montages thereby undermine the strict differentiation between the two realms, fiction and document, and open an epistemological space for the critique of language and ideology.

Source: Image used courtesy of Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach.

Photomontage

Photomontage includes a wide variety of practices based on the assemblage of primarily photographic material. Photomontage can be made from photographs and photo fragments cut with a blade from an existing source and pasted onto a support; from composite images of negatives fused in the darkroom; from excised and reassembled photographs that have been re-photographed to produce a seamless surface; or by using the crop, cut, and paste function in a computer program and reassembling a new photographic image. Text, color, drawing, painting, or object fragments can also be incorporated. The inter-war period, when photomontage was widely used as a persuasive medium, represented the apex of the genre. Photomontage was used for publicity and propaganda, particularly by artists affiliated with Constructivism, Dada, Surrealism, and the Bauhaus. In its dynamic reassembly of image and text, photomontage offered a visually stimulating picture with claims to documentation due to the photograph’s purported status as a document of the real. Photomontage both questioned and profited from this documentary standing. Based on mass-replicated images, photomontage could easily be reproduced, utilized for commercial and political posters, book jackets, book and journal illustrations, magazine covers and page layouts, advertisements, photomurals, exhibition catalogues, industrial-product brochures, department-store pamphlets, film advertising, and exhibition installation.

Organized around the structural principle of pictorial disruption and re-assembly, photomontage is considered a ‘‘symbolic form’’ or paradigm of the modern—its optical fragmentation and simultaneous competition of pictorial fragments conjured the accelerated social, economic, and technological transformations of the 20th century. Photomontage also imitated modern industrial production in its assembly of pre-fabricated, mass-replicable parts. In Germany, where photomontage was widely used, the connection of montage to industrial assembly line production is linguistically explicit; the German verb montieren means ‘‘to assemble’’ or ‘‘to fit,’’ while a Monteur is a mechanic or engineer. Photomontage was thus linked with mass reproduction and modern manufacturing rather than the institution of high art.

Berlin Dada is often credited with the ‘‘invention’’ of photomontage, the honor split between two competing factions: Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann on the one hand, and George Grosz and John Heartfield on the other. While on summer holiday in the Baltic Sea, Höch and Hausmann discovered in their rented cottage a color lithograph of military personnel onto which had been pasted the head of the fisherman’s son, evidently a soldier. These prints turned into photomontage were common in German homes before and during World War I, transforming stock, mass-produced military images into private mementos. Heartfield and Grosz also located their discovery of photomontage in wartime habits, namely the practice of sending postcards from the front onto which photograph clippings had been pasted, thus relaying in images what would have been censored in words. Though accounts of the origins of photomontage might vary, the discovery of photomontage by the avant-garde derived from a popular practice that reclaimed mass media images for individual use—that is, photomontage was widely used to galvanize popular opinion through modern, mass-reproducible means.