Overview

Film Subject Overview By Sapra, Rahul

Overview

The Film Section includes entries on a variety of modernist genres, periods, movements, directors, films, and critical modes aligned with modernist aims and intellectual attitudes. The entries are not confined to Europe and North America, but address film modernism in multiple countries across the globe (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, China, Cuba, Japan, India, Iran, Philippines, South Korea, Etc.). The entries attempt to provide students with a wide breadth of knowledge on modernist cinema, but it is by no means an exhaustive list, since there are diverse and contradictory interpretations of modernist cinema.

Modernism, a highly contentious and multilayered term, becomes even more difficult to define in the context of the cinema. Unlike literary or pictorial modernism, cinema did not have a well-established tradition to challenge and displace. In fact, from its inception, cinema was perceived as synonymous with modernity. However, while it adopted narrative and iconographic conventions from the turn-of-the-century stage and nineteenth-century realistic narrative, and quickly developed a stylistic and storytelling orthodoxy to which commercial productions adhered, it was simultaneously in dialogue with modernist aesthetics. A case in point is early cinema: largely made in innocence of modernist experiments in other arts, it was often championed by modernist critics and filmmakers and may indeed be seen as a vernacular avant-garde. The dominance of modernist movements such as French Impressionism, German Expressionism, Surrealism, and Dadaism led to highly experimental forms of cinema in the early twentieth century. Critics such as Noel Burch, André Gaudréault, and Tom Gunning have underlined the connections between the aesthetics of early cinema and the formal strategies of subsequent experimental film. During the 1920s, French Dadaists and Surrealists drew much inspiration from the anarchic atmosphere and unruliness of American slapstick comedy, whose echoes may be seen in René Clair’s or Luis Buñuel’s earlier productions. Even Classical Hollywood Cinema, which became in many ways the blueprint for commercial film and whose aesthetics and mode of production were often replicated in many national contexts outside the United States, was indeed in more or less self-conscious dialogue with currents of modernism. Formulaic and genre-dominated as it was, conventional narrative film, however, selectively assimilated some modernist formal devices and registered the influence of modern artistic idioms in art design and mise-en-scène in genres such as the musical and melodrama.

Outside the United States, modernism was more fully embraced by other national film industries. The British Documentary Film Movement experimented with avant-garde techniques to develop socially conscious, subjective cinema. Influenced by Impressionist paintings, French Impressionist cinema used the camera as a brush to express the emotional impression of the characters by letting visual effects take precedence over narrative storytelling. German Expressionism, influenced by the devastation caused by World War I, is perceived as the first major antirealist movement in film portraying internal and imaginative rather than objective reality, which undermined the conventions of naturalism. And during their brief heyday, from the mid-1920s to the early 1930s, the filmmakers of the Soviet Montage School implemented a discontinuous editing and unconventional framing to construct political films aligned with the ideology of the Soviet state.

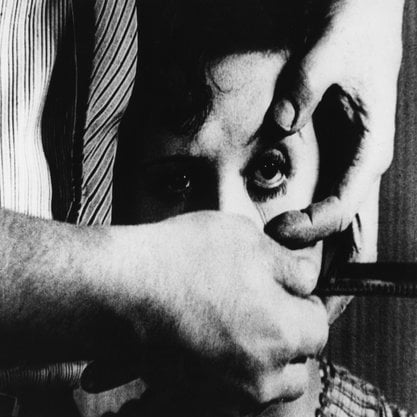

Dadaist films, mainly dominant in the 1920s, instead of luring viewers into film illusion, experimented with the film form to distort reality and perspective thereby making the familiar and mundane radically unfamiliar by experimenting with shapes, sculptures, and photography, and by creating optical illusions. Surrealist films also question reality by attempting to liberate the audience from social norms that repress human desire and imagination. Surrealist films deal with the irrational, the uncanny, and portray shocking images and absurd moments that impact the viewers’ unconscious. Most of these film movements spread across the globe, and due to overlapping characteristics they are loosely categorized as “Experimental” / “Avant-Garde” cinema. Building on the early disjunctive, discrepant film modernisms, there emerged other developments after World War II that continued to impact cinema until the late twentieth century: some of these are grouped under categories such as Feminist Film, City Films, Psychedelic Cinema, Dance Film, and Science Fiction Film. Some influential film movements include Underground Cinema and Cinema Novo.

One of the most influential post World War II developments was the emergence of Italian neorealist cinema, which brought forth a new form of realism and used nonprofessional actors in key roles, neglected classical narrative structure, and shot scenes on location in the city streets and country landscapes of war-torn Italy. The highly influential film critic André Bazin in “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema” emphasizes neorealism’s reinstatement of ambiguity to reality through its frequent rejection of montage. Decolonization following the post World War II period opened news areas for the neorealist cinema: the Philippines, Brazil, India, Cuba, China, and Mexico made significant contributions to neorealism.

However, the most important film movement in the context of modernism is generally regarded to be the French New Wave, since it can be identified as cinema’s modernism. By the time of the emergence of the French New Wave in the late 1950s, cinema had not only developed its own history and tradition that it could challenge, but cinema also had its own critical and theoretical discourse that could reflect upon its own aesthetic traditions. The French New Wave, like modernism, is not a homogeneous category, but the films share some common characteristics: they are subversive, experimental, playful, generally not bound to the studio system, and some important techniques include long takes and discontinuous editing. Many of the French New Wave directors were also noteworthy critics who contributed to the pathbreaking magazine Cahiers du Cinéma. The New Wave not only spread to other European countries, but also made an impact across the globe. The Czechoslovak New Wave directors questioned socialist realism and critiqued the Communist Party. Japanese New Wave was led by younger and rebellious filmmakers who criticized the older generation for lacking with sociopolitical realities of the time. In addition to using aesthetic and thematic features of the New Wave cinema, Japanese New Wave also employed avant-garde documentary filmmaking practices. Korean New Wave, which ran from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, avoided melodrama to revisit the country’s traumatic history, and younger directors were frequently involved in dissent against the country’s dictatorship. The Iranian New Wave undermined the conventions of Film Farsi, the mainstream Iranian film industry. There is no homogeneous Iranian New Wave, but the films generally depict everyday life, provide a strong critique of sociopolitical conditions, and also use the documentary style to merge fact and fiction.

Several of the films, genres, and movements mentioned above can be considered to be outside the period that is generally called Modernism, and therefore many would situate them in the Postmodern period. However, a number of forms of cinema even after the 1960s and until the late twentieth century carried forward several significant formal and thematic characteristics of early modernism. John Orr, in Cinema and Modernity, argues that cinema’s capacity for “irony, for pastiche, for constant self-reflection, and for putting everything in quotation marks, [is] not ‘postmodern’ at all, but on the contrary, [has] been an essential feature of cinema’s continuing encounter with modernity.”