Overview

Constructivism By Fowler, Alan; Rosenbaum, Roman; Johnson, Michael; Fernando Cortés Saavedra, David; Fowler, Alan; Rosenbaum, Roman; Johnson, Michael; Fernando Cortés Saavedra, David

Overview

Abstract

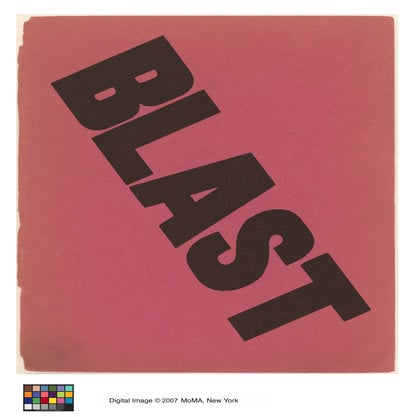

Prior to World War II, Constructivism attracted little interest from British artists apart from the few involved with Circle in 1937. Circle consisted of a publication and accompanying exhibition and was the first comprehensive presentation of constructivist work in London. It was organized jointly by Ben Nicholson (1894–1982), the Russian émigré sculptor Naum Gabo, and the architect Lesley Martin, and was publicized as an international survey of constructive art.

British Constructivism

Prior to World War II, Constructivism attracted little interest from British artists apart from the few involved with Circle in 1937. Circle consisted of a publication and accompanying exhibition and was the first comprehensive presentation of constructivist work in London. It was organized jointly by Ben Nicholson (1894–1982), the Russian émigré sculptor Naum Gabo, and the architect Lesley Martin, and was publicized as an international survey of constructive art. After the war, three main groups have worked within the constructivist tradition – the Constructionists (1951–1960) grouped around Victor Pasmore, the British branch of Groupe Espace (1953–1960) led by Paule Vezelay, and the Systems Group (1960–1977) founded by Malcolm Hughes and Jeffrey Steele. Until the mid-1960s, most of these artists subscribed to the constructivist concept of a synthesis of architecture, painting, and sculpture in the creation of a new environment for a technological society. After the 1960s, this utopian concept was abandoned and the focus became the internal constructional logic of the individual art work. Although there has been no group activity since 1976, surviving artists from the Constructionist and Systems groups, together with other younger artists, are still working in a constructivist mode.

Marlow Moss (1890–1958) was the first British-born constructivist artist, though at that time, 1928, she was living in Paris and her work made little impact in Britain. In the late 1930s, many European artists, including the Russian constructivist sculptor, Naum Gabo (1890–1977), came to London to escape Nazi and Soviet oppression. Befriended by Ben Nicholson, Gabo proposed a collaboration in the production of a book and exhibition as a survey of international constructive art and architecture. They were joined by the modernist architect, Leslie Martin. Their book, Circle, published in 1937, featured 56 participants of whom 10 were British, although the constructivist identity of several was weak. Circle’s activity was ended by World War II.

In 1951, the Constructionist group was founded by Victor Pasmore (1908–1998) with the painters Adrian Heath, John Ernest, Anthony Hill, Kenneth Martin, Mary Martin, Gillian Wise, and the sculptor Robert Adams. During the 1950s they exhibited in group shows with other abstractionists, organized exhibitions of their own and published three broadsheets. In their second broadsheet, Pasmore wrote that the artist “can practice scientifically … and can make constructions according to objective principles” (Broadsheet No. 2, 1952, unpaginated). His reference to making constructions related to the production of three-dimensional reliefs instead of two-dimensional paintings, while by objective principles he indicated the use of mathematical or geometric systems to determine the structure of the art object. Anthony Hill became a leading exponent of this approach. Kenneth Martin distinguished between imagery abstracted from the natural world and constructive abstraction when he wrote: “It is not a reduction to simple forms of the complex scene before us. It is the building by simple elements of an expressive whole” (undated note, Tate Archive). The Constructionist group disbanded at the end of the 1950s, though most members continued to work in a constructive mode for the remainder of their careers.

Groupe Espace, founded in Paris by André Bloc in 1951, was a successor to the pre-war De Stijl movement and the Bauhaus. Bloc invited Paule Vezelay (1892–1984), who until World War II had been living in Paris, to become the Groupe’s London delegué. She enrolled two architects, two sculptors and eight painters, but failed to attract the Constructionists after an abortive attempt by Victor Pasmore to take over the group’s leadership. The group’s sole London exhibition in 1955 included entries from leading European constructivists, and members also took part in the parent Groupe’s exhibitions abroad. Vezelay was dedicated more to abstraction in general than to constructivism, though she supported the constructivist concept of a synthesis of the arts. The best known of the other members were the sculptor Geoffrey Clarke, the painters Vera Spencer and Charles Howard, and the architect Vivien Pilley. Marlow Moss, now back in Britain, was also a member. The group folded in 1960.

In 1969, several British abstract painters working in a constructivist mode exhibited in Helsinki in a show, organized by Jeffrey Steele (1931–), entitled “Systeemi-System: An Exhibition of Syntactic Art from Britain.” The term “syntactic” referred to the constructivist concept of the art work being built-up from a vocabulary of geometric elements. Steele and Malcolm Hughes (1920–1997) invited all the artists involved to form the Systems Group – the term “systems” referring to the use of rational underlying “rules” (often mathematical) in determining the art work’s structure. The members were Steele, Hughes, Jean Spencer, Peter Lowe, Colin Pope, Michael Kidner, Peter Sedgeley, and David Saunders, plus Wise and Ernest from the Constructionists. During the 1970s they held three of their own exhibitions, and participated in numerous other group shows in Britain and abroad. The group disbanded towards the end of the 1970s. However, all its members continued to work in a constructivist mode throughout their careers, and its survivors are among the artists still producing constructivist work today.

Constructivist art has featured far more strongly in mainland Europe than in Britain, and most constructive British artists see their work as aligned with that of European artists such as Max Bill, Richard Lohse and Georges Vantongerloo. The Systems Group artists established close links with similar art groups in Germany, Poland, Switzerland and Italy, and exhibited far more frequently there than in Britain, where American abstract expressionism has made a more powerful impact than the cooler, precise and more rational characteristics of European Constructivism.

Japanese Constructivism (構成主義, Kōseishugi)

The philosophy of constructivism was introduced to Japan by Murayama Tomoyoshi (村山 知義, 1901–1977), a Japanese painter born in Tokyo and raised by a Christian mother active in the pacifist movement. Though he was initially encouraged to pursue watercolors and traditional Japanese painting, Murayama was later drawn to philosophy, particularly the works of German philosophers Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche. He converted to Christianity after being assaulted by fellow students for disseminating his mother's pacifist views. Murayama entered Tokyo Imperial University in 1921 with the intention of studying philosophy, but soon left to study art and drama at the Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany. He returned from Germany in 1923 to introduce Constructivism to Japan and became one of the leaders of Japan’s avant-garde art and theatre movement. Murayama first posited his artistic theory of “conscious constructivism” (意識的構成主義, ishikiteki koseishugi) in April 1923. He championed an expansion of the subject matter of art to incorporate “the entirety of life” (全人生, zen-jinsei), which suggested the inclusion of the full range of human experiences and emotions in modern life.

The term Constructivism originated in the abstract artistic movement in Russia, but the term is used in Japan across a wide variety of academic disciplines ranging from the arts to politics, social studies and psychology, to signify the interdependence between human experience and the realm of ideas related to social norms, interests and identities. Constructivism also developed into an international aesthetic trend that espoused an avant-garde tendency in order to fulfil specific social purposes and eschew the autonomy of art. This endeavor led to several modern art movements including German Bauhaus design and the Japanese MAVO movement as an offspring also inspired by Dadaism.

Constructivists proposed to replace art’s traditional concern with composition and refocus on the process of construction itself. Constructivists were involved in the construction of a new society and it was this political and social motivation that attracted Murayama and his fellow Constructivists to the genre, and in particular the work of Wassily Kandinsky. Later, Murayama became dissatisfied with Constructivism’s detachment from reality and developed his own style by using collages of real objects to provoke concrete associations. He termed this method “conscious constructivism,” which developed into the MAVO (マヴォ) movement. The Japanese Mavoists sought to annihilate the boundaries between art and everyday life, and rebelled against convention by combining industrial products with painting or printmaking in collage. Social mobilization was part of the movement, which engaged in artistic protests against social injustice portrayed through the use of theatrical eroticism and the mocking of public morality.

Russian Constructivism

Russian constructivism was an avant-garde movement that emerged from the ferment of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. Responding to the transformative potential of the Machine Age, constructivism helped to formulate an aesthetic inspired by machines and reflecting the concerns of a modern, industrial society. It thereby had a profound impact upon modernist architecture and design in the West, influencing both the De Stijl movement and the Bauhaus. Constructivists saw themselves as artist-engineers charged with building the infrastructure of a new society and the movement briefly enjoyed the support of the Soviet government, which commandeered this modern, abstract style to express its ideals. Constructivism was manifested in many cultural fields, including art, architecture, graphic design, theatre and cinema.

The origins of constructivism lay in the pre-revolutionary work of Vladimir Tatlin, an artist based in Moscow. He abandoned the romantic notion of the artist as a capricious genius and dressed in worker's overalls as a display of solidarity with the proletariat. Inspired by cubism and Italian futurism, Tatlin created abstract geometric constructions or “painterly reliefs” using industrial materials such as steel, iron, and glass. The sculptors Antoine Pevsner and Naum Gabo published a Realistic Manifesto in 1920, which articulated this new approach. The term “constructivism” is thought to have been derived from the manifesto, although other sources have been suggested. Constructivism was consolidated as a movement at INKhUK (Institute of Artistic Culture) in Moscow. The First Working Group of Constructivists was founded here in 1921 and included Alexei Gan, Liubov Popova, Alexandr Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova, and Alexandr Vesnin, all of whom were committed to a materialist and politically orientated approach. Important outlets for constructivism were the journals LEF (1923–1925) and Novyi LEF (1927–1929), launched by the Left Front for Artists.

The constructivists were among the first artists to embrace the new age of machinery and mass production. In this period, Russia was still largely a rural, peasant country with little heavy industry, but the Bolshevik Revolution promised a workers’ paradise built with the awesome power of modern technology. In this climate of political fervor, the machine became a metaphor for progress and constructivists established a machine aesthetic that was later developed at the Bauhaus.

Anticipating a proletarian Utopia, many constructivists devoted themselves to the ideological cause of Bolshevism. They rejected the notion of art as the preserve of a bourgeois elite and aimed to demolish the barriers between art and industry. The propaganda value of their dynamic constructions and graphics was recognized by the state, and numerous agencies were set up to cultivate it. For example, Narkompros, the People's Commissariat of Enlightenment, was a cultural and educational ministry headed by Anatoliy Lunacharsky. Vladimir Tatlin was appointed director of IZO (the visual art section of Narkompros) and became a key figure in the implementation of Lenin’s Plan for Monumental Propaganda. Constructivists were recruited to create agitprop (agitation-propaganda) trains that toured the country emblazoned with striking graphic designs, thereby spreading the revolutionary message to Russia’s largely illiterate rural population.

Tatlin believed that architecture was linked to engineering and saw the architect as an anonymous worker serving society. His audacious Monument to the Third International (1919–1920) was envisaged as a 396m tower of iron, glass, and steel proclaiming the glory of the revolution. This visionary design represented the union of art and construction – its sculptural form of two intertwining spirals and a soaring diagonal component was rendered in a lattice construction suggestive of raw engineering rather than academic architecture. The tower also functioned as a machine, featuring four transparent volumes that rotated at different speeds (yearly, monthly, daily and hourly). These were intended to house government offices for legislation, administration, information and cinematic projection. High costs and political opposition prevented Tatlin from executing the design, and only a scale model was ever built. Tatlin subsequently directed his talents into industrial production, with only limited success, creating designs for furniture, workers' overalls and an economical stove intended for mass production.

Initially, constructivism was concerned with three-dimensional constructions, but the aesthetic was soon extended to other media. El Lissitsky created visual propaganda drawing on the ideas of futurism and cubism. Inspired by military maps, his famous poster Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1920) used abstract imagery and diagonal lines of force to represent the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922.

The designer Varvara Stepanova developed a powerful visual style for graphics, textiles and clothing. Her work made extensive use of photomontage, manipulating found photographic images to create jarring juxtapositions. Diagonal lines and unstable compositions conveyed the energy and dynamism associated with modernity. Her contribution to the publication The Results of the First Five-Year Plan (1932) mythologized the technological achievements of Stalin’s first program of economic reform.

Embracing Bolshevik ideology, Stepanova saw clothing as a symbol of egalitarian values and a tool for social cohesion. She designed workers’ clothing, sportswear and textiles, many of which were mass-produced by the First State Textile Printing Factory from 1923 to 1924. Based on bold, geometric silhouettes and abstract patterns, constructivist clothing mechanized the human body and posited it as a biological machine working in synchronicity with industrial society.

Stepanova’s husband Alexandr Rodchenko was a painter and graphic designer who created propaganda posters, book covers and state advertising in a similarly dynamic style. His work eliminated unnecessary detail and emphasized diagonal composition. He experimented with photography and photomontage, and designed inter-titles for Dziga Vertov’s film Kino Eye (1924). Photomontage was analogous to editing in film and directors such as Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein began experimenting with dynamic editing techniques based on the juxtaposition of images. Films such as Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925) can be regarded as constructivist works. Alongside Stepanova’s experiments in fashion design, Rodchenko explored the concept of the overall, which he saw as the epitome of working class dress. For maximum functionality, he included detachable pockets and sleeves, and stressed the construction of the garment by emphasizing the components with bold seams and zips.

Architecture was a crucial area of constructivist practice as this was the medium with potential to build the new infrastructure for post-revolutionary Russia. Constructivist architecture was developed by Nikolai Ladovsky, Ivan Leonidov, El Lissitsky, Konstantin Melnikov and the brothers Alexandr, Leonid and Viktor Vesnin in buildings that emphasized functionalism and new construction techniques, while translating the dynamism of constructivist art and design into architectonic terms. Public buildings, exhibition designs and stage sets were the focus of these experiments and many projects remained unbuilt due to the technological limitations of the era.

Political support for constructivism waned after 1932, when Stalin outlawed abstract art and imposed the reactionary doctrine of Socialist realism. This severely curtailed constructivist activity, although some exponents continued to produce innovative work, particularly in the fields of poster design and typography. Beyond Russia, constructivism influenced a wide spectrum of artists and designers.

Source: Photo Scala, Florence © Rodchenko & Stepanova Archive, DACS, RAO 2016.

Uruguayan Constructivism

Uruguayan Constructivism was a dynamic artistic and cultural force embodied by the Asociación de Arte Constructivo (1934–1942) (AAC) and later on by the Taller Torres-García (1942–1965) (TTG) with enormous local and national resonance setting the bases for the growth of concrete art in South-America during the 1950s as well as for the development of constructivist mural painting and conceptual art in the continent.

After a 43-year absence from his country, Joaquín Torres-García arrived to Montevideo in 1934 with the intention of founding a School of Arts of Uruguay. On December 25, 1934 his project materialized with the first exhibition of the AAC, which presented a third option on the national panorama of the arts dominated until then by social realism and academic naturalism. The group integrated by Joaquín Torres-García, Carmelo de Arzadun, Julián Álvares Márques, Inés Caprario, Maria Sara Gumendez, Jorge Nieto, Héctor Ragni, Lila Rivas, Carmelo Rivello, Augusto Torres, Nicolas Urta, Rosa Acle, Alberto Soriano, and María Cañizas developed an art based on geometry, frontality and the use of Indo-American Pictograms directly influenced by the master´s aesthetic doctrine of Universalismo Constructivo which valued the inner quality of materials as wood, cardboard, textiles, stone and metal. The ACC published the Magazine Circulo y Cuadrado between 1936 and 1943, which acted as a bridge between European modernism and Uruguayan geometric and constructive art while also being a platform for the exposure of the association’s ideas on ancient Indo-American art and its iconography.

Coinciding with a loss of momentum in the multi-artistic activities of the ACC already visible from 1939, the association’s painting workshop morphed into the TTG, which was officially founded on October 14, 1942. Its founder members where young artists of a new generation, among them Francisco Matta, Julio Alpuy, Gonzalo Fonseca, Zoma Baitler, Edgardo Ribeiro, Alceu Robeiro, Héctor Ragni, Luis Gentieu, Daniel de los Santos, Luis San Vicente, and Torres-García’s sons Horacio and Augusto Torres. To these members, another 42 were added in the following three years, many of whom were to become recognized artists during the 1950s. Between May and July 1944, 21 members of the TTG worked on 35 constructivist mural paintings for the Martirené aisle of the hospital of the Colonia Saint-bois in Montevideo, rendering through bright primary colors the grid system and flat schematic figuration typical of the AAC. This, their most influential work, also marked the active integration of female artists into public commissions of such magnitude. Responding to the attacks of the more conservative fractions of Uruguayan criticism, the TTG published Removedor, a belligerent magazine devoted to the defense of constructive art.

After the death of Torres-García the TTG continued functioning until the middle of the 1960s. José Collel and Gonzalo Fonseca recreated lost pre-Colombian ceramics techniques while the latter also made monumental cement sculptures in Mexico and in the United States. Augusto and Horacio Torres executed commissions of furniture and monumental brick murals and succeeded in recreating the texture and quality of stained glass using plastic panels. Further echoes of the aesthetic forwarded by the ACC and TTG can be found in later manifestations of concrete and constructive art in South-America.

Further Reading

Alloway, Lawrence (1954) Nine Abstract Artists, London: Alec Tiranti Ltd.

Bukh, Alexander (2010) Japan's National Identity and Foreign Policy: Russia as Japan's 'Other', London: Routledge.

Bulanti, Maria Laura (2008) El Taller Torres-Garcia Y Los Murales Del Hospital Saint-Bois: Testimonios Para Su Historia, Montevideo: Liberia Linardi y Risso.

Cohen, Jean-Louis and Lodder, C. (2011) Building the Revolution: Soviet Art and Architecture, 1915–1935, London: Royal Academy of Arts.

Constructionists> (1951, 1952, 1953) Broadsheets 1, 2, 3, London: Tate Archive.

Dabrowski, Magdalena, Dickerman, L.,Galassi, P., and Rodchenko, V.A. (1998) Aleksandr Rodchenko, New York: Museum of Modern Art.

Fowler, A. (2007) 'Paule Vezelay and Grroupe Espace', Burlington Magazine, March: 173-179.

Fowler, A. (2005) 'Constructivism and Systems Art in Britain', Elements of Abstraction, Southampton: Southampton City Art Gallery.

Fowler, A. (2008) A Rational Aesthetic: The Systems Group and Associated Artists, Southampton: Southampton City Art Gallery.

Gabo, N., Martin, J. and Nicholson, B. (1937) Circle, London: Faber & Faber.

Gough, Maria (2005) The Artist as Producer: Russian Constructivism in Revolution, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Grieve, A. (2005) Constructed Abstract Art in England: A Neglected Avant-garde, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Khan-Magomedov, Selim Omarovich (1987) Alexandr Vesnin and Russian Constructivism, Lund: Humphries.

Larking, Matthew (2012) 'Mayo, the Movement that Rocked Japan's Art Scene', Japan Times, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2012/04/26/arts/mavo-the-movement-that-rocked-japans-art-scene-2/#.UjPJHj8wNMI (accessed 14 September 2013).

Lawson, Stephanie and Tannaka, Seiko (2011) 'War Memories and Japan's 'Normalization' as an International Actor: a Critical Analysis', European Journal of International Relations 17(3): 405–428.

Lodder, Christina (1985) Russian Constructivism, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Margolin, Victor (1997) The Struggle for Utopia: Rodchenko, Lissitzky, Moholy-Nagy, 1917–1946, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Milner, John (1983) Vladimir Tatlin and the Russian Avant-Garde, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Peluffo Linari, Gabriel (1999) Historia de la Pintura Urguaya tomo 2. Entre Localismo Y Universalismo: Representaciones de La Modernidad (1930–1960) [versch. Aufl.], Montevideo: Ed. de la Banda Oriental.

Ramirez, Mari Carmen and Buzio de Torres, Cecilia (ed.) (1992) El Taller Torres-Garcia: The School of the South and its Legacy, Austin: University of Texas Press.

Rickey, George (1995) Constructivism: Origins and Evolution, New York: George Braziller.

Torres Garcia, Joaquin, Dias, Alejandro, Perera, Jimena and Torres, Demian Diaz (2004) Universalimo Constructivo: Óleos, Maderas Y Dibujos ; 28 de Julia Al 15 de Diciembre de 2004: Museo Torres Garcia, Montevideo: Museo Torres Garcia.

Weisenfeld, Gennifer (1994) 'Mayo's Conscious Constructivism: Art, Individualism, and Daily LIfe in Interwar Japan', Art Journal 55(3): 64–73.

Weisenfeld, Gennifer (2002) Mayo: Japanese Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1905–1931, Berkeley: University of California Press.