Overview

Bauhaus By Baumhoff, Anja; Funkenstein, Susan; Baumhoff, Anja; Funkenstein, Susan

Overview

Abstract

In 1919 a young architect named Walter Gropius initiated one of the most modern art schools of the twentieth century in the city of Weimar in Thuringia, Germany. He called it the Bauhaus. Its unusual name can be translated as “building hut,” indicating its connection with the medieval tradition of cathedral building and the idea of a total work of art.

The Bauhaus is not only famous for its ideas or its buildings in Weimar and Dessau but also for its members, among them the three directors of the school—the architects Walter Gropius (1919–1928), Hannes Meyer (1928–1930), and Mies van der Rohe (1930–1932). Teachers included renowned modern artists such as Lyonel Feininger, Vassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László and Lucia Moholy-Nagy, Herbert Bayer, Marcel Breuer, Wilhelm Wagenfeld, Anni und Josef Albers, Oskar Schlemmer, Marianne Brandt, and Gunta Stölzl. All of them endorsed modernism at a time when modern art and abstraction was far from being accepted—contemporaries understood it first of all to be a post-war rebellion similar to the then notorious Dada movement. The overall aim of the Bauhaus was to redefine fundaments of composition and construction as well as the use of colors.

Bauhaus Design (1919–1933)

In 1919 a young architect named Walter Gropius initiated one of the most modern art schools of the twentieth century in the city of Weimar in Thuringia, Germany. He called it the Bauhaus. Its unusual name can be translated as “building hut,” indicating its connection with the medieval tradition of cathedral building and the idea of a total work of art.

The Bauhaus is not only famous for its ideas or its buildings in Weimar and Dessau but also for its members, among them the three directors of the school—the architects Walter Gropius (1919–1928), Hannes Meyer (1928–1930), and Mies van der Rohe (1930–1932). Teachers included renowned modern artists such as Lyonel Feininger, Vassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László and Lucia Moholy-Nagy, Herbert Bayer, Marcel Breuer, Wilhelm Wagenfeld, Anni und Josef Albers, Oskar Schlemmer, Marianne Brandt, and Gunta Stölzl. All of them endorsed modernism at a time when modern art and abstraction was far from being accepted—contemporaries understood it first of all to be a post-war rebellion similar to the then notorious Dada movement. The overall aim of the Bauhaus was to redefine fundaments of composition and construction as well as the use of colors.

In 1919 a young architect named Walter Gropius initiated one of the most modern art schools of the twentieth century in the city of Weimar in Thuringia, Germany. He called it the Bauhaus. Its unusual name can be translated as “building hut,” indicating its connection with the medieval tradition of cathedral building and the idea of a total work of art. In its early days the school was still very much influenced by Expressionism and teachers were called master instead of professor. However, many of the Bauhaus ideas were less original than they might seem, having already been developed before the First World War.

An important part of the Bauhaus’ contribution the modernism were its publications, the so-called Bauhausbücher, a series of fourteen books, and the Bauhaus journal. Members of the school also helped to develop the Deutsche Industrie Norm (DIN) in order to standardize buildings and furniture and thus pave the way for mass production. But the Bauhaus is not only famous for its ideas or its buildings in Weimar and Dessau. It is also known for its members, among them the three directors of the school—the architects Walter Gropius (1919–1928), Hannes Meyer (1928–1930), and Mies van der Rohe (1930–1932). Teachers included renowned modern artists such as Lyonel Feininger, Vassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, László and Lucia Moholy-Nagy, Herbert Bayer, Marcel Breuer, Wilhelm Wagenfeld, Anni und Josef Albers, Oskar Schlemmer, Marianne Brandt, and Gunta Stölzl. All of them endorsed modernism at a time when modern art and abstraction was far from being accepted—contemporaries understood it first of all to be a post-war rebellion similar to the then notorious Dada movement. The overall aim of the Bauhaus was to redefine fundaments of composition and construction as well as the use of colors.

The early Bauhaus sought to combine the teaching of art as well as design and in order to achieve this the former fine arts academy merged with the old school for applied art in Weimar. This way Gropius hoped to secure the education of a new type of artist beyond all the usual academic specialization. In order to further art education the school developed new teaching methods like the preliminary course, which owed its existence to the artist Johannes Itten. In addition, workshops were set up as the base for any art was to be found in handcraft. In order to remove any distinction between fine arts and applied arts, artists and craftsmen led the workshops together.

Emerging out of its Expressionist phase, the school changed direction in 1923 and embarked on the idea of “art and technology—a new unity.” The Bauhaus workshops now started to produce prototypes for industry which were functional and showed a modern aesthetic. Wanting to unite all the arts and crafts into a total work of art under the leadership of architecture, they intended not only to produce new forms but to create a new world. A settlement was planned but did not materialize due to lack of funds. Nevertheless, a start was made and for the 1923 exhibition the Haus am Horn was erected, which was a model house designed by the painter Georg Muche. It ignited further discussion because of its radical design, flat roof and white walls.

The exhibition of 1923 is one of the highlights of the Bauhaus legacy, although its reception among contemporaries was rather mixed. The exhibition came about because the Weimar Bauhaus was state-funded and its radical ambitions provoked so much opposition in Germany that it then had to justify its activities. Walter Gropius hoped that the big exhibition of 1923 would finally calm his critics—but far from it. The fact that the Bauhaus wanted to bring about a new style of life expressed in a new style of living that needed a new kind of interior design was seen as foreign, non-German even, and simply alien and cold. Bauhaus modernism clashed significantly with the dominant contemporary taste, which was characterized by eclecticism, cheap neo-classicist decoration, and velvety drapes surrounded by opulent furniture, commonly identified as a bourgeois style of life. Thus the school was too advanced for its time.

Someone who helped to steer the Bauhaus ship in the modernist direction was the Hungarian constructivist Lászlo Mohol-Nagy, who joined the school in 1923 when Johannes Itten left. The Dutch artist and writer, Theo van Doesburg, founder of the Dutch De Stijl group, also strongly influenced the Bauhaus after 1921 and propagated radical modernism.

The new slogan “art and technology a new unity” in combination with Louis Sullivan’s motto “form follows function,” the reduction of design to minimalist forms combined with a black and white interior as well as with simple basic colors characterized the Bauhaus legacy. That said, the Bauhaus was more than a reductionist design of basic geometric forms and colors, flat roofs, and polished interiors.

When Walter Gropius left the Dessau institute in 1928 he was succeeded by the Swiss architect Hannes Meyer, who had a more radical approach and reformed the school’s program in order to promote more socially responsible architecture and design. Meyer wanted the Bauhaus to help improve the living conditions of the poor, raise hygienic standards, and build affordable houses. He captured this in the slogan “Volksbedarf statt Luxusbedarf”—to build for the masses and not produce luxury goods for the few. During his brief time as director the Bauhaus workshops focused even more on industry and mass production. He set up the first architectural class in 1927 and a workshop for photography in 1929.

Other workshops in Dessau were typography and advertising, carpentry, metal, weaving, wall painting, sculpture, and the stage workshop. The more arts and crafts-oriented workshops like pottery and bookbinding did not make the move to Dessau, where Gropius had constructed the now famous Bauhaus building and several houses for the masters. His successor, Hannes Meyer, lost his position after only two years to Mies van der Rohe, who took over as director in 1930. Again, right-wing political forces had won. Van der Rohe changed the course of the school one more time and tried to focus more strongly on architecture. But even though he managed to calm the school’s intense political climate in order to satisfy Bauhaus critics, he could not prevent the National Socialists from closing it down. In Berlin, the Bauhaus existed for only a few months, which did not leave him enough time or money to establish the school anew.

The Bauhaus encompassed about 1250 members during its time and always had a male-dominated image. But female students made up roughly one third of the institution. Most women worked in the weaving workshop, a few in the pottery or bookbinding workshops. There were exceptions, including Marianne Brandt, who is today one of the most celebrated members of the metal workshop. Despite the rather conventional gender stereotypes present at the Bauhaus and within the modern movement in general, many courageous female artists left their mark during that time.

Bauhaus Dance Movement

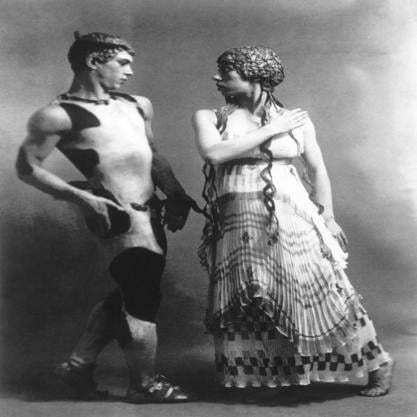

Dance and movement were central to the Bauhaus’ institutional and vernacular history. There, students, faculty, and guests experienced dance through modernist theatrical settings, movement exercises, and social dancing, all of which conveyed Bauhaus aesthetic ideas and fostered community. Similar to other Bauhaus explorations, dance forms transitioned in aesthetics and ideals from Expressionism to Constructivism.

The Theater Workshop (founded Summer 1921) served as dance’s institutional home. Lothar Schreyer, its first Master of Form (1921–23), advocated for an Expressionist, mystical, and spiritual theatre but less for dance. Dance became more vital in the workshop under Schreyer’s successor, Oskar Schlemmer (1923–29). His most famous choreography, the Triadic Ballet (Das Triadische Ballett, 1922–32), was a humorous, abstract, and modern take on ballet costumes and movements, but the large costumes hindered the dancers’ movements and evoked war-torn bodies. Broken into three acts, most versions of the choreography featured a ‘gay burlesque’ classical ballet act in yellow, a “ceremonious and solemn” character dancing act in pink, and a “mystical fantasy” abstract act in black (Schlemmer 1925, 34).

Schlemmer’s ideals of Bauhaus concert dance are evident in his Bauhaus Dances (Die Bauhaustänze, 1926–29), a series of brief Constructivist-leaning works. These non-narrative, non-allegorical choreographies explored dancers’ movements across the stage’s axes. Performers utilized industrial materials and abstract shapes (with metal sheets, blocks, poles, and hoops) within those geometric confines, whereas primary colors complemented the color theory teachings in the preliminary course. Bulky, padded costumes abstracted dancers’ bodies and evoked marionettes, dolls, and automata. After Schlemmer’s departure, the Theatre Workshop was dissolved.

Movement and dance also thrived separately from the Theatre Workshop. Gertrud Grunow offered lessons on harmony (1920–24). Aligned with Johannes Itten, Grunow investigated how elements such as sound, form, and color physically and psychically affected the individual, such that internal experiences could turn into outward expression through rhythmic dance. In contrast to Grunow’s spiritual teachings, Karla Grosch taught women’s gymnastics (1928–32) along Constructivist lines, combining athleticism with the geometric arrangement of human form. Activities in her courses included throwing medicine balls, gymnastics, and yoga, often executed out-of-doors or on the Bauhaus-Dessau roof. Grosch’s mentor Gret Palucca, a modernist dancer recognized for her high springs and optimistic dance style, guest-performed at the Bauhaus in 1925 and 1927 and befriended many artists. An example of the Bauhaus interdisciplinarity, Wassily Kandinsky’s “Dance Curves” essay and drawings explore the geometry underlying Palucca’s movements, whereas the students engaged with her modernity and celebrity through photographs and typographic experiments (Funkenstein 2012, 45–62; Funkenstein 2007, 389–406).

Central to the school’s celebratory atmosphere was social dancing. Annual theme and costume parties included the White Festival (Das Weiße Fest, 1926), the Beard, Nose, and Heart Festival (Das Bart-Nasen-Herzensfest, 1928), and the Metallic Festival (Das Metallische Fest, 1929). Organized by Theatre Workshop students supervised by Schlemmer, the festivals transformed the Bauhaus buildings with elaborate decorations and attendees danced to music from the Bauhaus Band. Dance steps were a mix of jazz dance such as the shimmy and Charleston with folk dancing. Frequent parties throughout the year, whether off-site student parties or birthday celebrations, also featured impromptu social dancing.

Located in the former East Germany, the Dessau Bauhaus was restored in 1976 and served as a cultural and design center until the fall of the Wall. Since 1994 the Bauhaus Foundation has regularly programmed experimental theatre, dance, and music in the restored space, as well as reconstructed theatre and dance works first staged there in the 1920s.

.jpg)